A softening economy characterized by a loss of high-paying jobs darkened the economic picture painted at the 2016 Economic Forecast Update presented by the A. Gary Anderson Center for Economic Research at Chapman University on Tuesday, June 28.

President Jim Doti said jobs in Orange County would likely grow by just 2.5 percent during 2016, most in low-paying industries. The so-called “California Miracle” has largely been driven by the Silicon Valley, Doti said.

“Orange County has under-performed,” he said.

Doti also took a few minutes to comment on Brexit, which occurred too recently for commentary to be included in the published report. Contrary to other economists, as well as media and political pundits, Doti said he considered the UK decision to leave the European Union to be an overdue wake up call.

“The European Union has been a failure. It’s been one bureaucratic, regulatory mess sponsoring crony capitalism,” he said.

Moreover, Great Britain was at best a marginal member of the European Union and the predictions of a devastated stock market are overblown, he said. When people understand that Brexit “is a good thing and not a bad thing, markets will stabilize again,” he said.

Presented for the first time in Marybelle and Sebastian P. Musco Center for the Arts, the forecast update was also a tribute to the late Esmael Adibi, Ph.D., who was the director of the A. Gary Anderson Center. The update was dedicated to Adibi’s memory, and several tribute videos were included in the presentation. Doti and Adibi created the economic research model that has been used to prepare the forecasts since 1979.

Doti shared with the audience the words printed on a wristband he wore that was created by Adibi’s MBA students in honor of their late professor – “Greatness never departs.”

“When it comes to Essie, that is so true,” Doti said.

Following is a summary of the forecast:

2016 U.S. FORECAST UPDATE

Overview

As we assess the U.S. economy, there are more signs of weakness than pockets of strength. These emerging signs suggest the seven-year recovery is weakening, especially since late last year. The following categories, for example, are experiencing slower growth:

- 3-month moving average of the change in jobs

- Number of temporary workers

- Nonfarm labor productivity

- Industrial production

Some categories are showing outright declines:

- Nonresidential investment

- Corporate earnings

Although it is too early to call for a recession, it now appears that the current recovery is in its latter stages and nearing an end point. Before that point is reached, underlying growth in the U.S., as measured by real GDP, is likely to move from a two-to-three percent range to a one-to- two percent range.

Highlights

- The update forecast calls for a softening of real GDP growth from 2.4 percent in 2015 to 2.1 percent in 2016. Forecasted declines in consumer and investment spending growth overwhelm the relatively smaller positive effects from government and international trade.

- A number of factors are dampening consumer spending growth. Housing appreciation is beginning to stabilize and the stock market has experienced several downward corrections. After rising rapidly since the beginning of the recovery, household net worth has now stalled. While job growth has been relatively strong, there are signs of weakening labor market conditions. Rather than spending, consumers are saving more.

- While housing starts are forecasted to increase to a post-recession high of nearly 1.2 million units in 2016, the rate of growth is projected to decline from 10.7 percent in 2015 to 5.9 percent in 2016. Coupled with the sharp downturn in energy-related business investment that has negatively impacted nonresidential investment, we see total real investment growth dropping back significantly this year.

- While government spending growth is forecasted to increase, the impact of this uptick represents an increase in real GDP growth of only 0.24 percent.

- Although net exports is forecasted to continue declining in 2016 by 10.9 percent, that represents a lower rate of decrease than 2015’s 22.8 percent nosedive. A pickup in global economic growth will support higher U.S. export growth. In addition, the U.S. dollar is finally stabilizing in international exchange markets after a rapid run-up in late 2015.

- Despite slower real GDP growth, housing appreciation will continue, albeit at a slightly reduced rate. Even though housing affordability is continuing to decline, a tight supply of housing available for sale is keeping upward pressure on prices.

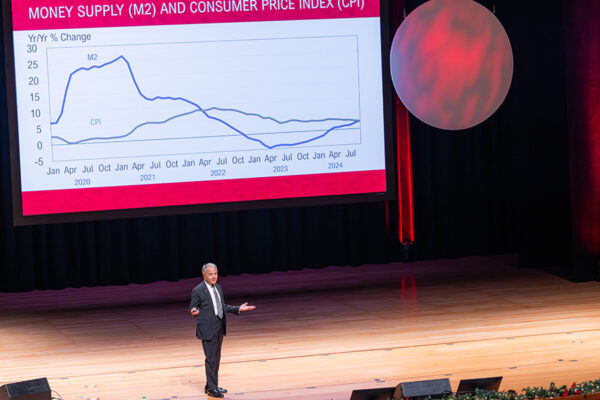

- With the current economic malaise, we don’t see any pressure on the part of the Fed to resurrect its earlier intentions of steadily increasing the federal funds rate in 2016. Hence, interest rates are forecasted to remain flat for the rest of the year.

2016 CALIFORNIA FORECAST UPDATE

Overview

On the surface, California’s economy appears to be growing more rapidly than the U.S.. For example, from 2007 to 2015, California experienced faster growth in the following categories:

- California’s aggregate job growth was 4.9 percent as compared to U.S. growth of 3.3 percent.

- Personal income in California increased 33.8 percent, while personal income in the U.S. increased 28.8 percent.

The “California Miracle” is also reflected in the state’s general fund revenues, which have increased 40 percent since the recession.

Looking beneath the surface, however, reveals a number of deep-seated structural problems in the state.

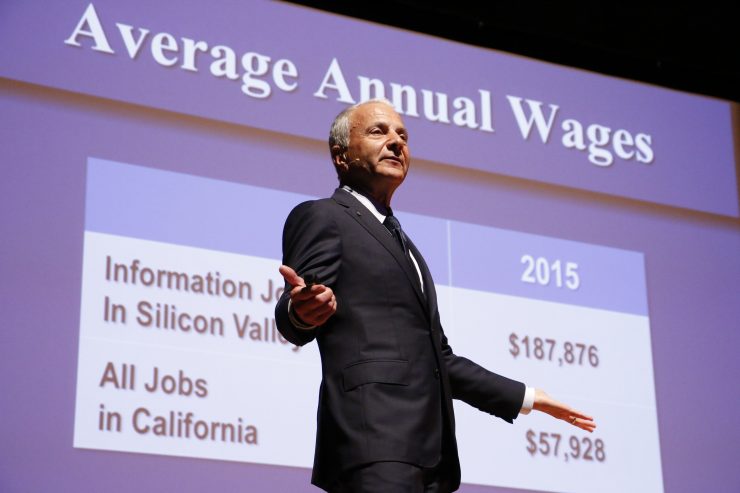

- California’s recovery is not broad-based but focused mainly on the five-county Silicon Valley area that includes San Francisco. For example, the Silicon Valley added 57,000 information-related jobs since 2007, while California was losing jobs in this high-paying sector. Information jobs in the Silicon Valley pay an average annual wage of $188,000 versus a $57,000 average for all jobs in California.

- Personal income tax receipts as a share of general fund revenues is now 65.8 percent versus 53.8 percent in fiscal year 2011-12. That makes California’s state government more vulnerable to economic downturns.

- The ratio of housing prices to average annual wages in California is 8.2 as compared to 4.2 in the U.S.

- California is losing high-paying manufacturing jobs faster than the U.S., particularly inLos Angeles that has shed 20 percent of its manufacturing jobs since 2007.

- The loss of manufacturing jobs in California, especially Los Angeles, has led to net outward migration (more Californians leaving the state than people from other U.S. states moving in) of about 170,000 over the last three years.

- California’s unfunded pension debt based on a 7.5 percent investment return is twice annual general fund revenues. At a more realistic 2 percent return, unfunded pension debt is 10 times annual general fund revenues, placing it over the trillion dollar mark.

Highlights

- The Anderson Center’s California job indicator suggests that the state’s job growth peaked at 3.3 percent in the third quarter of 2015 and will decline steadily in 2016. On an annual basis, we forecast payroll employment growth declining from 3.0 percent in 2015 to 2.5 percent in 2016. Such growth will result in the creation of about 400,000 new jobs this year.

The fact that the national and local economic variables that comprise the California job indicator are signaling a downturn in job growth does not necessarily indicate an imminent recession. But it does strongly suggest that the state is entering the final stages of recovery.

- Within job sectors, California is moving more rapidly than the U.S. in becoming more service rather than goods related. Since the beginning of the recovery in 2009, California’s growth in service-related jobs was 19.6 percent versus 15.6 for the nation. During that same period, California’s manufacturing jobs declined 1.0 percent while the U.S. picked up 3.7 percent.

- Even more telling is that within the services sector, the state’s information services jobs increased 10.9 percent as compared to a decline of 1.4 percent in the nation. The increase of about 50,000 high-paying information services jobs suggests that about $6.9 billion has been added to personal income in California.

- Mirroring the downward trend in job growth, personal income growth in California is forecasted to decline from 6.3 percent in 2015 to 5.4 percent in 2016.

- On a per capita basis, personal income in California was 8.4 percent higher than the U.S. in

2007 ($43,200 in California versus $39,800 in the U.S.). By 2015, the differential had widened to 10.3 percent ($52,700 in California versus $47,700 in the U.S.).

- Similar to national trends, the rate of growth in California’s residential permit valuation is forecasted to decrease. The projected drop in California will be greater, however, mainly because of the sharp uptick of 16.6 percent last year.

- We see construction spending, as measured by lagged real values of permit valuation, continuing on a downward trend. The forecasted average annual growth in construction spending of 6.5 percent in 2016 compares to 10.4 percent in 2015 and 19.5 percent in 2014.

- The current level of housing affordability coupled with a relatively tight supply of unsold housing will serve to push housing prices up by 5.7 percent in 2016, roughly equivalent to the 5.6 percent pace registered last year.

2016 ORANGE COUNTY FORECAST UPDATE

Overview

Since 2007, cumulative job growth of 2.8 percent in Orange County has lagged the U.S. (3.3 percent) and California (4.9 percent). Even more alarming is that most of these jobs are being generated in low-paying categories like education & health and leisure & hospitality. The

county is losing high-paying manufacturing jobs and not generating high-value-added jobs in the service sector. While the Silicon Valley is a job machine in generating information-related jobs, Orange County is losing them. As a result, Orange County’s per capita personal income, which in 2007 was 16.4 percent greater than that of California, is now only 8.7 percent higher.

Like Los Angeles, more people are leaving Orange County for other parts of the U.S. than those from the U.S. moving to the county. Although the number of people leaving each year is relatively low, the rate of outflow has doubled in the last two years.

Highlights

- Similar to what we observed in California, it now appears that Orange County hit a recovery peak in job growth of 3.5 percent in the third quarter of 2015. By the fourth quarter of this year, our forecast calls for job growth in the county to drop to 2.5 percent or an annual average of 2.6 percent. This compares to job growth of 3.2 percent in 2015.

As in the case of California, current trends

suggest that the county’s recovery is no longer holding its own but is in decline, with all explanatory factors pointing to slower growth.

- Total personal income growth in Orange County is forecasted to increase from 4.7 percent in 2015 to 5.2 percent in 2016—slightly lower than the 5.4 percent personal income growth forecasted for California.

- Taxable sales growth will continue to be lower in Orange County than in California. Orange County taxable sales growth is forecasted to increase from 3.1 percent in 2015 to 4.1 percent in 2016. This compares to an increase from 3.6 to 4.3 percent growth forecasted for California.

- Similar to California, residential permit valuation in the county is forecasted to decrease from 11.2 percent growth in 2015 to 4.5 percent growth in 2016. But this will be enough to bring residential permit valuation above the $3 billion level for the first time ever this year.

- Low mortgage rates and higher median family income coupled with a tight housing supply will keep upward pressure on housing prices. Housing appreciation in Orange County is forecasted from 2.7 percent in 2015 to 4.6 percent in 2016.

ABOUT THE ANDERSON CENTER FOR ECONOMIC RESEARCH

The A. Gary Anderson Center for Economic Research (ACER) was established in 1979 to provide data, facilities and support in order to encourage the faculty and students at Chapman University to engage in economic and business research of high quality, and to disseminate the results of this research to the community.

Add comment