California Scene painting was overlooked for several generations as being outside the mainstream of the nearly universal international artistic push toward abstraction. Scene painting is part of a movement that has been called – unfairly – conservative and reactionary. As this view goes, the overall movement of American Scene painting began as a 1920s-era reaction by certain artists against the rapid advance of technology, the growth of American cities and the burgeoning popularity of Modernist art.

Visit the Hilbert Museum

The rich history of California blossoms in Chapman University’s first museum – the Hilbert Museum of California Art, which opens on Friday, Feb. 26, at 167 N. Atchison St. The museum is the only one of its kind nationwide to showcase California Scene painting. Its debut exhibition, “Narrative Visions: 20th-Century California,” features a selection of works from the collection of paintings donated to Chapman by collectors Mark and Janet Hilbert.

Museum hours are Tuesday through Saturday, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m., closed on Sundays and Mondays. Admission is always free. For more information, visit the Museum’s website at www.hilbertmuseum.org.

American Scene painters – typified by the triumvirate of Thomas Hart Benton, Grant Wood and John Steuart Curry – celebrated the rural life, pastoral scenes, positive American virtues and representational art — that is, art with recognizable subject matter. Meanwhile, they rejected the influence of abstraction and of Europe – particularly France – on American art.

Certainly Benton and his followers in the Midwest were reacting against the abstractionist/Euro-centric mainstream. And within its time the American Scene movement was looked upon by the burgeoning modern art establishment in New York as quaint, backward-looking and parochial.

Yet, in some ways, the American Scene movement was indeed a real revolution, and Modernist to boot. It sought to establish a uniquely American form of art, drawing on local history and culture, distinct from Europe. And in many ways, it followed a thread that had carried on from the earliest days of American painting, which, in that time before fast transportation and communication, had developed local and regional “schools,” such as the Hudson River School of the 1860s.

When we come to California Scene painters, the life histories, purposes and goals of the artists were quite different from their compatriots in the Midwest. Many of the California painters were lured to the Golden State between the late-1920s and the 1950s by the promise of artistic employment offered by the movie and animation houses. Walt Disney, for example, selected artists for his studio based on their ability to tell a story in their works. There seemed no particular animus against Modernism or abstraction (indeed, Disney championed some forms of Modernist art in films like

Fantasia

, and in

Destino

, his hoped-for and uncompleted animated film short with surrealist Salvador Dali).

Among the collection pieces is

Discouraged Workers

by Ben Norris, which captures the mood of 1936 California.

California opened these artists to a new world where they were free to paint what they wished in their off-studio hours. The storylines they chose – portraying the everyday lives of factory workers, ranchers, carnival workers and others – were the myriad human tales of California as it grew and changed over the decades of the mid-20

th

century.

Thus, in many ways, the revolution of the California Scene movement was a

narrative

revolution. The artists weren’t reacting against any particular art movement (and as they moved into the 1950s and ‘60s, some of them began to embrace and experiment with increasingly abstractionist ideas). In fact, they were celebrating and narrating the many and diverse stories that make up the state of California, here at the edge of the country, on the Pacific Rim, with its singular outlook on the world.

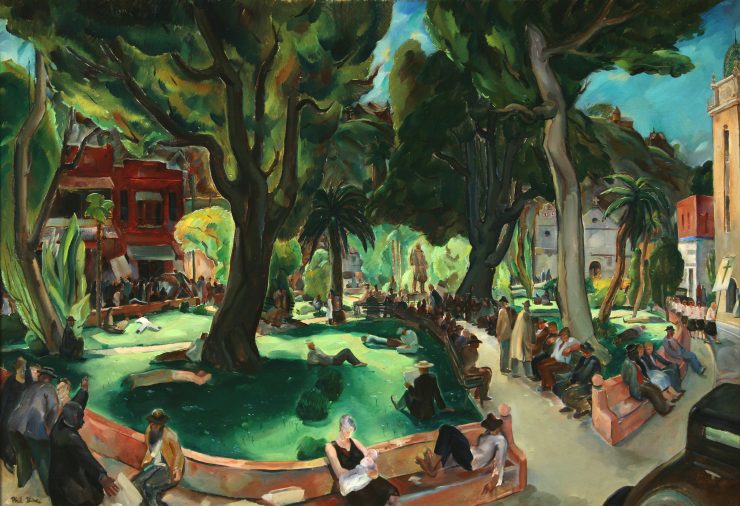

Featured image at top/

Sunday at the Plaza

by Phil Dike. This large-scale work was reproduced in Fortune magazine shortly after it was painted, and since the 1940s it has been part of at least eight important American museum exhibitions as well as being reproduced extensively.

Add comment