This story originally appeared in the spring 2013 issue of

Chapman Magazine

.

When author and historian Andrew Carroll first launched an archive of letters from the front lines of American history, he never expected it to grow 90,000 strong. Now the massive collection, full of eloquence and poignancy, starts a new life at Chapman.

Three months after the bloodiest day in American history, Antietam still chafed against the sensibilities of Civil War nurse Clara Barton. Memories were as close as her sleeve, which had been pierced by a bullet as the “Angel of the Battlefield” tended one of the 23,000 casualties. On Dec. 12, 1862, Barton braced for a new conflagration — the Union’s assault on Fredericksburg, Va. — and as she sat down to rest in a moonlit camp, surrounded by the sprawling Army of the Potomac, she couldn’t help but anticipate the next round of bloodletting.

Like so many who have served at the front lines of American history, she stole a moment of peace and shared her thoughts in a letter.

“The moon is shining through the soft haze with brightness almost prophetic,” she wrote to her cousin Vira. “For the last half hour I have stood alone in the awful stillness of its glimmering light gazing upon the strange sad scene around me striving to say, ‘Thy will Oh God be done.’

“The camp fires blaze with unwanted brightness, the sentry’s tread is still but quick — the acres of little shelter tents are dark and still as death, no wonder for as I gazed sorrowfully upon them, I thought I could almost hear the slow flap of the grim messenger’s wings, as one by one he sought and selected his victims for the morning sacrifice…

“Already the roll of the morning artillery is sounding in my ears. The battle draws near and I must catch one hour’s sleep for tomorrow’s labor.

“Good night darling cousin and Heaven grant you strength for your more peaceful and less terrible but not (less) weary days than mine.

“Yours in love, Clara.”

STAMP OF HISTORY

From Bunker Hill to Appomattox, Iwo Jima to Fallujah, the Enola Gay to the USS Abraham Lincoln, the history of America, to an extent both grand and tragic, is written across the pages of war. During the colonists’ fight for independence, those pages were parchment or linen. On a Japanese POW ship during World War II, Lt. Tommie Kennedy’s farewell message to his parents was scribbled with a stubby pencil on the backs of cherished photographs. On a peacekeeping mission in 1996, Major Tom O’Sullivan used an Army-issue computer to tap out an email to his son, Conor, whose birthday he was missing. He apologized for not being able to shop for a toy. Still, he told Conor, a special gift was on its way.

“It is a flag. This flag represents America and makes me proud each time I see it. When the people here in Bosnia see it on our uniforms, on our vehicles, or flying above our camps, they know that it represents freedom, and, for them, peace after many years of war…

“This flag was flown on the flagpole over the headquarters of Task Force 4-67 Armor, Camp Colt, in the Posavina Corridor of northern Bosnia-Herzegovina, on 16 September, 1996. It was flown in honor of you on your seventh birthday. Keep it and honor it always.

“Love, Dad.”

For 15 years, author and historian Andrew Carroll has collected these windows to history, amassing more than 90,000 letters and emails, representing the thoughts and emotions of service members in every conflict involving American troops. By now, this treasure trove of wartime correspondence is making a 2,700-mile journey from nondescript storage units in Washington, D.C., to its new home: a restored three-bedroom house a few blocks from the Orange campus of Chapman University.

Two bedrooms are being converted to house the letters — some to be stored in a dust-free, temperature-regulated, UV- protected space — with the third bedroom reserved for Carroll. When he’s not on the road doing research or speaking to educators, he’ll be at his new home, helping students, scholars and others gain insights from an archive that is being relaunched the Center for American War Letters at Chapman University.

The hope is that eventually funds will be raised to display the most prominent letters in a large exhibition space that will be open to the public year-round, Carroll said.

“I’ve been collecting and maintaining this archive essentially as a lone volunteer,” Carroll said. “I’m so excited that now, with the support of the Chapman community, we will have the resources to catalog, digitize and make accessible to people all over the world this archive of war letters.”

Carroll views this moment as transformational for the archive. The 90,000-letter figure is really just a rough estimate; the number could well be more than 100,000. And since he is no archivist, the true scholarly potential of the archive is still largely untapped. Only a fraction of the letters have been featured in documentaries and publications, including the three critically acclaimed anthologies Carroll has edited from the archive.

Carroll also wants everyone, but especially the Chapman community, to know that the center is actively seeking letters from all eras of American involvement in wars. When a parent or grandparent dies, it’s not unusual for loved ones to come across letters stashed in a closet, attic or basement. If those letters aren’t seen as historically important, sometimes they get tossed into the trash. That’s a tragedy, Carroll said.

“I know there are students at Chapman now who served in Iraq and Afghanistan,” he said. “I hope the launch of the center opens the flood gates of new letters, emails and DVDs, because they deserve to be valued and protected.”

SHARED JOURNEY

Chapman theatre professor John Benitz sees not just historical importance but human drama in the archive. In 2010, he read an article about the letters in National Geographic and reached out to Carroll in hopes of developing a play based on the letters. The two hit it off and began collaborating on If All the Sky Were Paper, which premiered three years ago in the Waltmar Theatre on campus.

Benitz was impressed with Carroll, and Carroll was impressed with Chapman.

“I just fell in love with the university,” Carroll said. “There is a great spirit on the campus, and the actors who presented the letters in the play showed enormous respect for the material and a passion for bringing it to the stage.

“It became clear to me that this was the place the letters were meant to be.”

When Carroll suggested the idea of donating the archive to Chapman, Chancellor Daniele Struppa “immediately got it,” Carroll said. “Not just for the letters’ scholarly value but to honor the sacrifices and memory of those who served, Daniele said, ‘How do we make this happen?’ That’s what sealed the deal for me.”

Struppa was struck by the universality of the stories in the letters, as well as their ability to unify those who read them.

“Ours is a very divided society, and these days we tend to demonize each other,” he said. “Some of us may be hawks and some may be doves on war. But we all can recognize those who sacrifice greatly for us. And especially within our university community, we all can find value in studying these living, vibrant historical documents.”

Struppa sees great potential for the archive as a teaching tool in a wide range of disciplines — history, political science, literature, theatre, peace studies and more. History Professor Jennifer Keene, Ph.D., an internationally recognized expert on World War I, has already brought letters into her classroom during Carroll’s previous visits to Chapman.

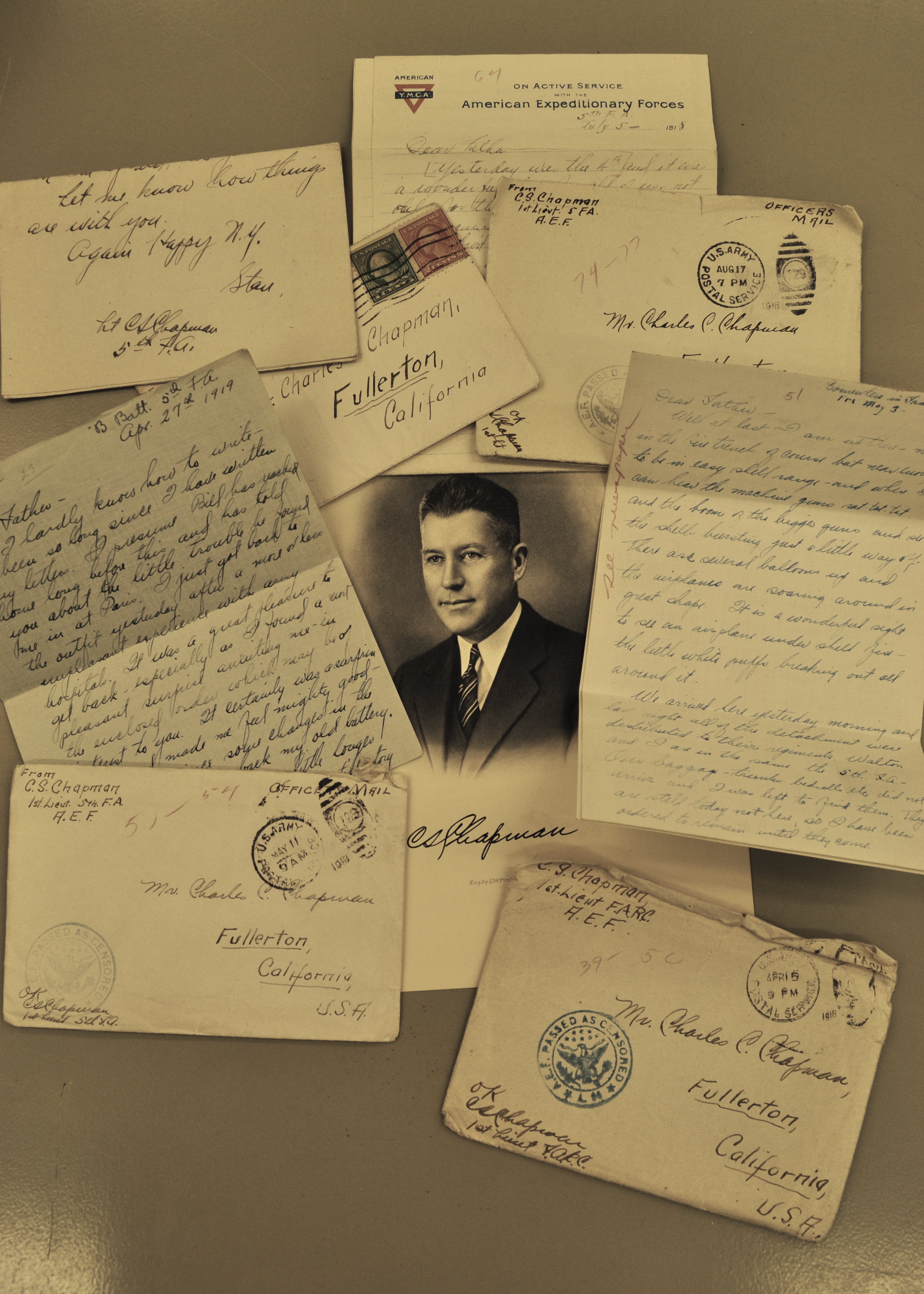

“The students are blown away,” Keene said. “There’s something about seeing actual artifacts. They see how people wrote, the stationary they wrote on. It becomes easier to start re-creating the world in which (the letter writers) lived.”

Next year will mark the centennial of the beginning of World War I, and Keene said that the occasion will offer Chapman “a test run” for including the archive in both a scholarly and public commemoration.

The letters add texture and help personalize a subject of immense complexity, she noted. A centennial symposium, lectures, a traveling exhibit of images and manuscripts, and lesson plans developed for a wide range of educators are among the possibilities.

But more than public events, Keene can’t wait for Chapman students to get their first chance to really dig into the archive.

“We’ll definitely have something to sink our teeth into,” she said.

Equally excited is Professor Marilyn Harran, Ph.D., holder of the Stern Chair in Holocaust Education and the founding director of the Rodgers Center for Holocaust Education and the Sala and Aron Samueli Holocaust Memorial Library at Chapman.

Harran sees the center as a catalyst for collaboration.

“At Chapman, we’re developing archives with great depth, and they may connect with each other in ways we don’t even know of yet,” Harran said, citing the Huell Howser California’s Gold collection as well as the photographs and artifacts of Holocaust survivor and rescuer Curt Lowens.

The war letters archive includes the reflections of soldiers who liberated Nazi death camps. Alongside the testimony of survivors, it’s powerful to present the voices of service members writing with immediacy about “something beyond their worst nightmares, something for which even combat couldn’t prepare them,” Harran said.

“Seeing the intersections and the differences in memory is like having many threads of one fabric,” Harran added. “When they interweave, it makes history real and deep and personal.”

It’s incredibly exciting to have the war letters collection, she noted, “but it’s also exciting to have Andy himself. He is so impassioned about making sure that memory is not lost.”

FROM A LOSS COMES INSPIRATION

Spend any time with Carroll and that passion is apparent. In May, he’ll embark on a 50-state tour to promote the center and encourage Americans to donate letters. At the same time, he and Benitz will oversee readings of the letters and performances of their stage collaboration inspired by the archive.

“This is a labor of love,” Carroll said. “It’s something I want to do for the rest of my life.”

Interestingly, Carroll didn’t come to that passion with obvious connections. He had little interest in history growing up, and no one in his immediate family served in the military. Then just before Christmas 1989, during his sophomore year as an English major at Columbia University, Carroll got the news from his father that the family’s home had burned down. Among the losses were cherished letters, including one from a friend who was in Tiananmen Square during the Chinese crackdown.

Later when he was sent a letter by an elderly cousin, detailing what he had seen at the Buchenwald concentration camp in 1945, Carroll thought about what a tragedy it would be to lose such an account.

“That planted the seed,” he said.

In 1998, Carroll was working with the American Poetry & Literacy Project when he became aware that war letters were being lost to indifference all across the country. So he started spreading the word of the need for an archive, including to syndicated columnist Dear Abby, who rallied her readers to the cause.

“I thought we’d get a couple of hundred letters and move on,” he said.

Instead, he got 15,000 — both originals and copies. He started giving talks at veterans’ halls and military bases, leading to documentaries on the History Channel and PBS, a Time magazine cover, and eventually Carroll’s best-selling book War Letters: Extraordinary Correspondence from American Wars. What he then dubbed the Legacy Project was off and running.

In more recent years, he has also traveled to dozens of countries on five continents in search of more war correspondence,

the best of which he has detailed in two subsequent anthologies.

Meeting veterans and championing the cause of preservation have inspired Carroll, but no more so than the letters themselves. He has spent countless hours reading them, finding that in addition to the details of everyday life, they are full of eloquence, selflessness and even humor under the most trying of circumstances.

“I had no idea the extent of the sacrifice troops make during wartime,” he said. “It goes beyond injury and casualties. It’s about not being there when a child is born; it’s about the stress on relationships; it’s about the psychological impact of seeing horrific things.”

With the archive at more than 90,000 letters, it’s easy to imagine that all of the powerful stories already have been told. Not so, Carroll said.

“Every time I think we’ve exhausted the subject matter of love, fear, courage, someone sends me a letter that’s unlike any I’ve read before.”

And what has him most excited is his expectation that this new chapter in the archive’s history will be its most vibrant.

“I really feel like we’ve just scratched the surface of what’s out there and what’s possible,” he said.

Add comment