A tsunami of fears washed over Professor Christopher Bader, who struggled to keep up as he scribbled on the whiteboard in Smith Hall room 216.

Terrorist attacks, earthquakes, identity theft, Obamacare, school shootings, clowns — the suggestions of things that might scare Americans poured from his students at a pace that had Bader fearing he would run out of room to record them.

So this is what it looks like at the headwaters of social science research. Or at least it is when you combine the enthusiasm of students with a research idea whose time has arrived.

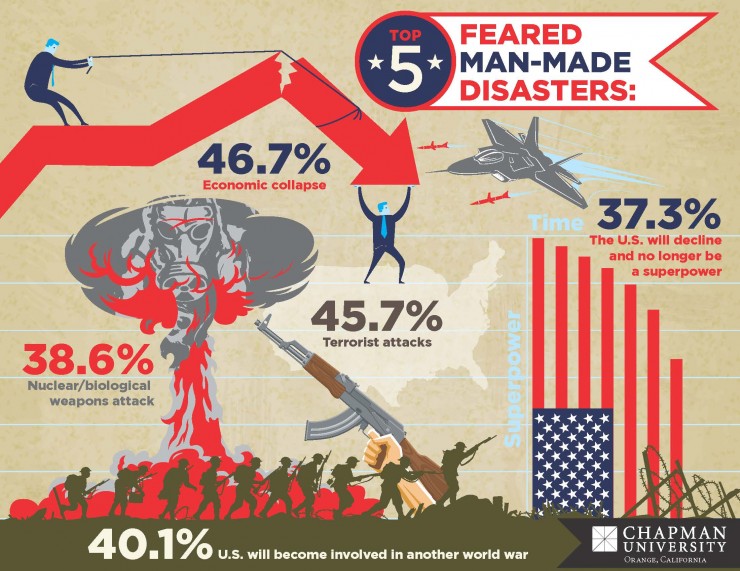

Among the findings of the inaugural Chapman University Survey on American Fears:

- Americans are most afraid of walking alone at night.

- The Internet is also a source of great trepidation, with identity theft and general “safety on the Internet” ranking 2-3 on the list of fears. That puts them just ahead of being the victim of a mass/random shooting and having to speak in public.

- In general, America harbors a fear of crime that far surpasses the actual problem.

Complete survey findings and analysis are at chapman.edu/fearsurvey.

Over the 10 months since Bader’s winter Interterm class first convened, the words on that whiteboard morphed into the first comprehensive nationwide study on what strikes fear in Americans. Bader and Chapman University colleagues Ed Day and Ann Gordon set out to fill a gap in our cultural understanding — and, just maybe, to start the process of repairing the social fabric by illuminating the consequences of our fears. For starters, what they got was a window to a nation on edge.

The Chapman researchers titled the crime section of the survey results “The Sky Is Falling (and a Serial Killer is Chasing Me).”

“The majority of Americans not only fear crimes such as child abductions, gang violence and sexual assaults, but they also believe these crimes (and others) have increased over the past 20 years,” says Day, Ph.D., who led this portion of the research and analysis.

Meanwhile, data compiled by police agencies and the FBI consistently show that crime has decreased over the past two decades.

“Criminologists often get angry responses when we try to tell people the crime rate has gone down,” adds Day, chair of the Department of Sociology and director of the Earl Babbie Research Center, which is the home of the fear survey at Chapman.

Must-Fear TV

Why the huge disconnect between fears and reality on crime? In a word: television.

“TV profits from that fear; they get high ratings from it,” Bader says. “Every one of these crimes occurs less often than it did 10 years ago, but if a single one happens, it’s all over the news. In fact, the rarer it is, the more coverage you see.”

There’s clarity in survey answers that reveal education levels and TV viewing habits, Bader adds. “Beyond whether you’re white or black, Republican or Democrat, we want to know if you’re watching 48 Hours, Dateline and 20/20,” he says.

The researchers hope that by shedding light on the link between TV coverage and oversized fears of crime, they can, in some small way, help close the gap between perception and reality.

“I believe that these fears are decaying the social fabric,” Bader says. “Fears make us stay away from public spaces, from our neighbors, from helping others. If I had a pie-in-the-sky wish, it would be that we could help people understand that they don’t need to be so afraid. The world is actually becoming a safer place.”

Fears can become self-fulfilling prophecies, the researchers note.

“When people stay away from public spaces because they’re afraid of bad things happening, then bad things move in,” Day says. “The park can become the place you were afraid it was.”

“I’m not optimistic,” Bader adds, “because there will be a lot more messaging on the opposite end from what we’re trying to get out there. But I do hope that we can have some small effect on the narrative.”

Disaster Inaction

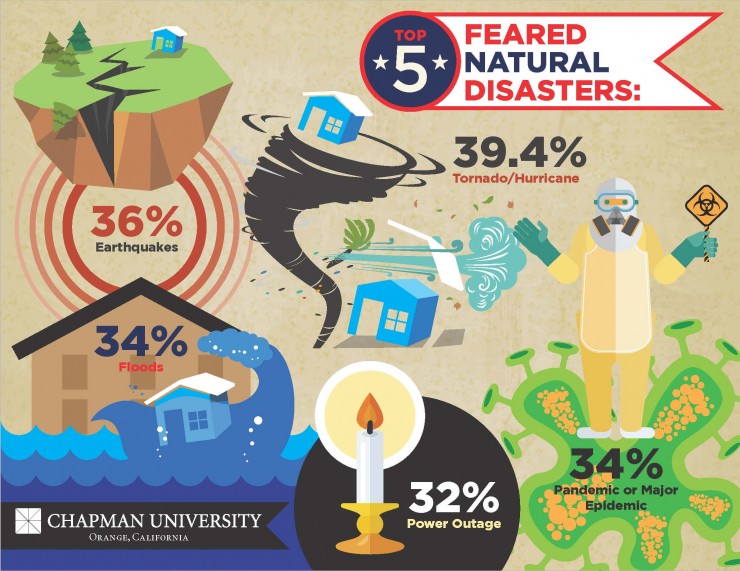

In addition to a section on crime, the survey covers fears about disasters. Topping this list are tornadoes, hurricanes, earthquakes, floods, a pandemic or major epidemic and a power outage.

Despite these concerns, only 25 percent of Americans have put together a disaster-preparedness kit with suggested items like food, water and medical supplies. Organizations such as the Red Cross and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) tell people they should be prepared to be without electricity and other services for at least 72 hours after a disaster. But the message isn’t getting through, says Gordon, Ph.D., the architect of this survey section.

“We need better communication strategies,” notes the political science professor and director of Chapman’s Henley Lab, which provides tools and training for students to perform statistical analysis. “We’re doing follow-up to examine why so many Americans remain unprepared despite the lessons from recent natural disasters.”

Gordon is an expert in political communication, and she’s concerned that current efforts to prompt disaster-preparedness seem to have the opposite effect.

“One response to fear is to become even more fearful and, as a result, paralyzed,” she says. “We want to build resilient communities.”

A ‘Most Rewarding Experience’

For professors Bader, Day and Gordon, the act of launching The Chapman Survey on American Fears is just one step in a long-term research project. They plan to tweak the list of questions every year, reflecting cultural changes. And over time, they hope to understand more deeply the social forces and effects of fear.

Students will continue to be a key part of the process.

Tyler Jones ’16 was in the class that helped develop the initial survey and calls it “the most rewarding experience I’ve had at Chapman.”

Before the students started suggesting possible topics for fear questions, they performed a range of research. And after they helped prepare a first draft of the survey, they collaborated on the hard work of whittling 30 pages down to the 11-page questionnaire that ultimately went into the field.

Along the way, the students faced the scrutiny of a faculty panel that made them defend the validity of each question.

“The students were amazing,” Bader says. “No one got flustered, despite withering questions. I told them on day one, if you don’t leave this room a little mad, then you don’t care about it enough.”

The rigorous process not only sharpened the survey’s focus but also vetted questions for bias. The final result is a research tool about which the whole team can take pride, Bader says.

“This project is really a credit to our students,” he says. “We hope it grows in its coverage and becomes an integral part of the culture here at Chapman.”

Lessons of Preppers

To better understand effective messaging about disaster preparedness, Professor Gordon and her students are studying “preppers” — those who channel their disaster fears into extreme action.

“We want to know who they are, what they’re afraid of, what they respond to and what they’re recommending to each other,” she says. “Why is it that this community is prepared when the rest of us aren’t?”

Preppers definitely believe in and respond to communication, Gordon says. She and her students draw lessons from the thousands of online videos, blogs, websites and TV shows in which preppers share their readiness tips. There’s even a dating site for preppers.

“It’s like other dating sites, except that here love means 100 gallons of water and a sustainable garden,” says Matt Lyons ’15, a double major in economics and political science who’s working on a senior thesis about preparedness communication.

In September, Gordon and Lyons traveled to North Carolina to experience Prepper Camp — sort of a Comic-Con for the extreme-preparedness set. There, they attended seminars such as “Blacksmithing on the Cheap” and “Bugging out by Boat,” and they conversed with dozens of preppers, who provided plenty of insights. For instance:

-

- Instead of throwing up their hands at the size of the readiness task, preppers tend to take it a day, week and month at a time. Gordon thinks aid agencies might get more people to prepare if they took such a systematic approach. “Vulnerable communities may look at a task that takes hours and $200 as unattainable,” Gordon says. “So maybe it’s ‘get water’ one week and ‘buy batteries’ the next.”

-

- Prepper messaging not only inspires readiness but also redundancy. “They mean it when they say, ‘Two is one, and one is none,’” Gordon relates.

-

- Preppers are big on showing rather than telling, which reinforces the importance of visuals in effective readiness communication. Research by Gordon and her team shows that simply adding photos to online lists of preparedness steps gets more people to act.

Student Matt Lyons ’15 and Professor Ann Gordon learned about everything from blacksmithing to archery during a visit to Prepper Camp in North Carolina.

Photo at top: Professors Edward Day, Christopher Bader and Ann Gordon team up to launch The Chapman Survey on American Fears, which Bader calls “a credit to our students,” who contribute greatly to the ongoing research.

Illustrations by Ryan Tolentino ’02.

Dr. Day and Dr. Gordon – my two favorite Chapman professors! Very cool project guys – proud alum 🙂

My greatest fear is to have one of my daughters abducted and never seeing her again. I’m not afraid of earthquakes, tsunami’s or walking at night.

I guess I’m a prepper, but my greatest fear is that some executive will cancel my favorite TV show without resolving last season’s cliffhangers. I think “prepper” is used too frequently as a term of derision, and without understanding of the societal spectrum the community inhabits.