This post appeared in the fall 2014 issue of

Chapman Magazine.

“The most beautiful experience we can have is the mysterious – the fundamental emotion which stands at the cradle of true art and true science.”– ALBERT EINSTEIN

Science and art weren’t always at opposite ends of the academic spectrum. The geniuses of the Renaissance — foremost among them Leonardo da Vinci — synthesized art and science as part of their attempt to understand and depict the workings of the real world. Art and the sciences were discussed widely and with equal fervor by Renaissance Neo-Platonists, and that hand-in-hand synergy continued through the great Age of Enlightenment and into the Victorian era.

When did these two roads to knowledge diverge? They haven’t, really. Science has always been considered one of the classical academic “arts,” and even today many universities combine humanities and sciences in one college, school or academic unit. At Chapman University, today’s Wilkinson College of Humanities and Social Sciences was Wilkinson College of Letters and Sciences — combining humanities and all the sciences — until less than a decade ago, when Schmid College of Science and Technology was created in 2006.

But in today’s popular mindset, it seems, there never were two disciplines further apart. Most people (supported by views in the popular media) perceive scientists as white-coated eggheads pursuing their research slowly and methodically and concerned only with dry facts, while disheveled, bohemian artists soar on the wings of their imaginations, creating their own worlds out of pure fancy.

In creating “The Intersection of Art and Science” at Chapman three years ago — first as a January Interterm class and for the past two years as a semester-long class — art professor Lia Halloran seeks to bridge that misconception. She allows her students to immerse themselves in science and then to create art from the experience: particularly from the perspectives of astronomy, astrophysics and current projects at NASA.

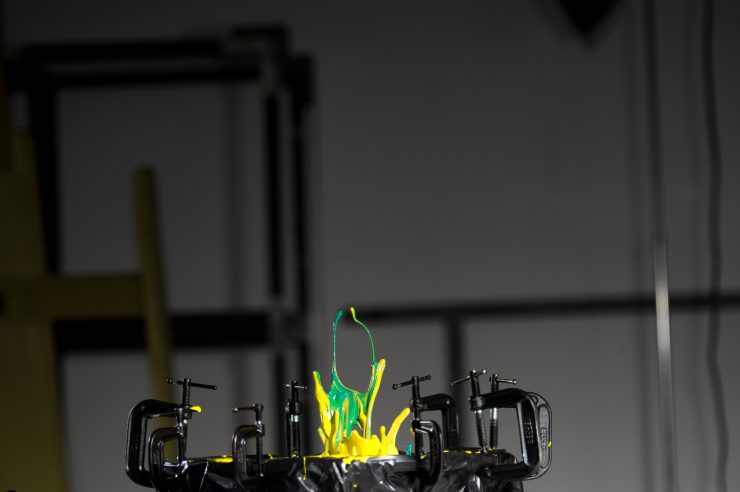

Seth Josephson ’15 prepares to work on his abstract painting, using a magnet to manipulate ferrofluid from below.

Halloran is a working artist whose love of science really took off in high school when she landed a position as an “explainer” at the San Francisco Exploratorium. At one time she seriously considered a career as an astronaut, and she entered UCLA as a double major in art and astrophysics before eventually earning a BFA in fine art. She went on to get an MFA at Yale, where she started making art about science.

View Lia Halloran’s art on her website.

“I was highly influenced by the work of Kip Thorne, the CalTech physicist,” she says. “I was making paintings about black holes. I spent three months in the Chilean desert looking for black holes with a lot of physicists, standing at telescopes.”

One of her images — from when she connected black holes with skateboarding to come up with the concept “Dark Skate” — is now in the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain. Her work is featured in many other prominent collections, galleries and museums, and has been published in

The New York Times

,

The New Yorker

,

The Boston Globe

, the

Los Angeles Times

, ArtNews and

New York

magazine, among others.

A “sound bath” is one way to experience the meditative and mysterious Integratron in the Mojave Desert.

“Connecting this Chapman art class to NASA, engineering and design is important,” Halloran says. “By narrowing the science focus, the class goes from being something conceptual and distant — and perhaps difficult for students to relate to — to something practical. It allows them to wrap their heads around it.”

The class is historically based — “there are a lot of readings in the history of science and the history of art” — as well as being a practicum in the making of art inspired by science, Halloran says.

One of the high points of Halloran’s class is a visit to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Canada Flintridge, where students talk to and work with JPL scientists.

“They learn valuable lessons,” she says. “People at JPL say you have to be a ‘cowboy’ or you’re never going to get anywhere; you have to think outside the box, and that’s totally encouraged. That’s how all artists need to think, too. I almost feel that my students have a better idea of what they’re trying to do than most students would, because they know what it means to come up against a problem, have no idea how to solve it, bang their heads around it, and then come up with something truly new.”

“I believe that art and science are inherently connected through curiosity,” says student Seth Josephson ’15, who took the class last spring. “Good artists and scientists are curious about the world, and work to understand their environment more fully. They share an interest in the unknown and attempt to make it known. The main difference, I think, is perception of the world versus reality. Artists deal mostly with understanding through the lens of our senses, where scientists primarily deal with objectivity and the laws of nature. I think professionals in either field should incorporate principles from the other to drive their ideas.”

Halloran received an education grant to add extra perks to the class, which has enabled her to do things like take the class to experience the famous Integratron in Joshua Tree, Calif. Built in the early 1950s by a true California eccentric named George Van Tassel, the Integratron “is based on the design of Moses’ tabernacle, the writings of Nikola Tesla and telepathic directions from extraterrestrials,” explains a plaque on the building.

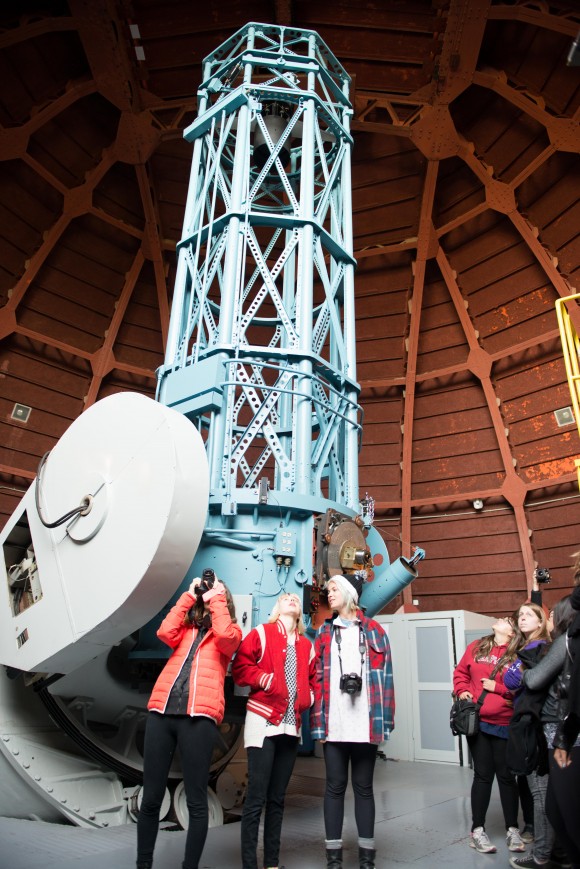

Students looking up at the telescope.

“Oh, the Integratron,” Halloran says with a laugh. “It’s a bizarre place — a domed building out in the desert where the spiritually minded go to meditate and take ‘sound baths’ for healing. I know, it sounds really hokey, but actually it’s the perfect place for the intersection of art and science. That was a fantastic field trip.”

Student Madeline Lucas ’14 reminisced on

the class blog

about the Integratron visit: “When someone stands at the center of the room… they hear sound in a way that they have never heard. The room harbors and spirals sound vibrations so amazingly. Our sound bath was rejuvenating and soothing; you could feel the vibrations all around.”

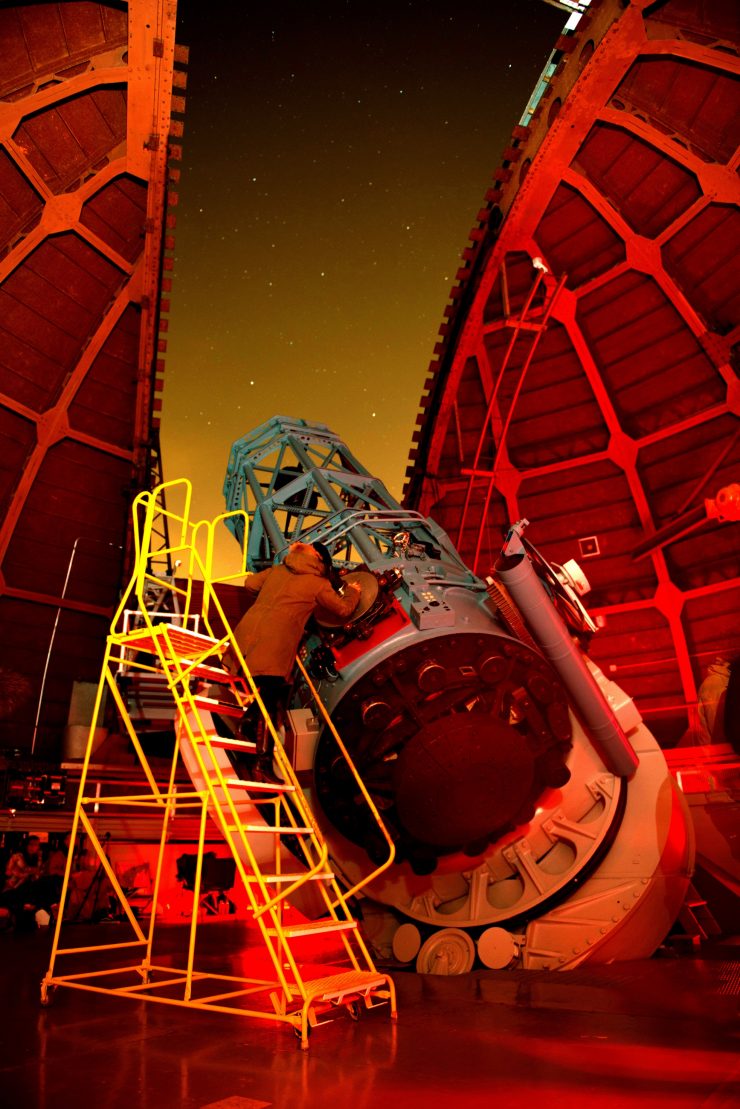

Perhaps the students’ most memorable experience was when Halloran used the grant to rent the prestigious Mount Wilson Observatory for a night. Located in the San Gabriel Mountains northeast of Los Angeles, the observatory boasts two of the most important telescopes in the world: the 60-inch Hale, built in 1908, and the 100-inch Hooker, built in 1917 and once the largest telescope on the planet. Both are among the world’s preeminent scientific instruments.

“I wanted to take pictures of my students when they looked through the Hale telescope at Saturn,” Halloran recounts. “I’ve seen it time and time again: you look at it and you’re suddenly reminded that you’re on a rock hurtling through space.”

“When we toured the largest telescope, I couldn’t help but visualize the astronomers working all night on that precarious equipment, making groundbreaking discoveries that completely changed not only the field of science but the way that humans perceive the universe,” student Kelsey Hart ’15 wrote on

the class blog

. “To be in such a charged space was a unique experience that I knew I would not encounter in other courses. Above all, seeing Saturn in the eyepiece of the 60-inch telescope blew my mind. It was difficult to comprehend how I could see something so unimaginably far away with nothing but the aid of a very old piece of equipment.”

Following their experiences communing with scientists, faraway planets and sound baths, Halloran’s students turn to creating art.

“On the visit to Mount Wilson, for example, they were assigned to produce one print, knowing these photos would be on view at a JPL open house later,” says Halloran.

“But this class is not to illustrate science. The point is not to catch them up on physics and have them try to understand all these things, but that they can create and demonstrate the experience, not the description, of science perhaps better than some of the scientists can. When we watch a rocket take off, do we need to know the engineering of it? Do you need to know what the solid rocket booster is made of? No — because you’re completely engrossed in the experience of it. And that’s what I want for these students — for them to have an openminded, engaged way of looking at science.

“I’m so impressed with the work of these student artists — I can hardly think of another class where I’ve felt like this. They’re working conceptually and technically on par with some of the working galleries in Los Angeles. I’m pinching myself, and I’m already thinking about what we can accomplish next year.”

Ethan Young ’14 occupies his own art installation, which combines sound and light using projection mapping.

Photo at top: The historic 60-inch telescope at the Mount Wilson Observatory is home base for a night of astronomical exploration and timed exposure photography by Chapman University students.

Yes, yes, yes! We need to remind our students (and those who forgot) that subject areas were never meant to be separated from one another. They became divided in order for humans to understand our world in smaller pieces. Very Cool Article. Thank you.

Love this article – and great to see that Chapman doesn’t sequester its students in their little majors, but allows learning and exploration across disciplines (just like most of the good careers in the “real world”…). Good job, Chapman.