This story appeared in the fall 2014

Chapman Magazine

.

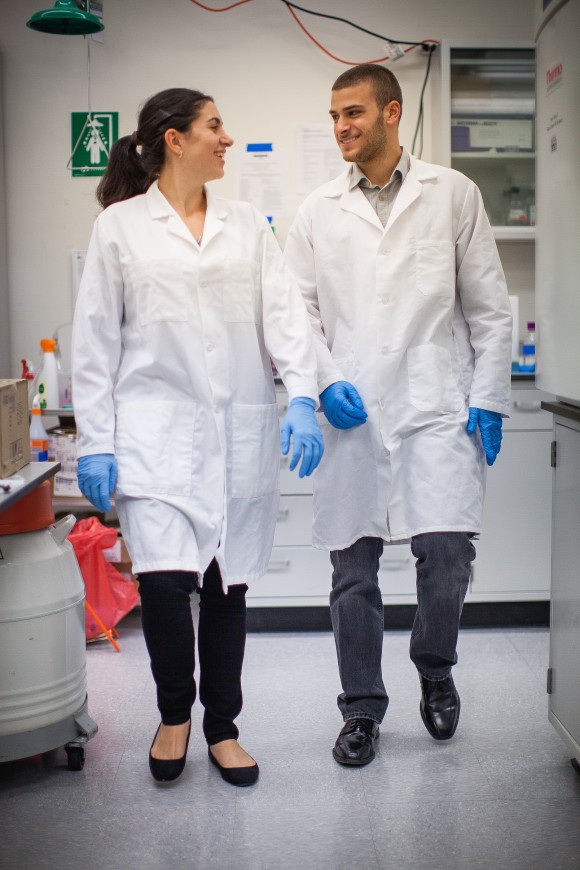

During a season of war in their homelands, two Chapman biology students sustain an enduring lab partnership by focusing on friendship and a passion for research.

As partnerships go, this is hardly a buddy-movie scenario. You won’t find a Butch or a Sundance in your typical bio-chem lab; likewise a Thelma or a Louise. That just isn’t the way lab partnerships work. In this spotless and serious realm, where the stainless-steel surfaces gleam but the real work is done in the half-light of obscurity, the bond between partners tends to be more subtle and cerebral.

Which brings us to Lena Haddad ’15 and Dor Shoshan ’15, both Chapman University biology majors and chemistry minors performing research on parallel tracks toward better detection and treatment of prostate and pancreatic cancer. The two self-certified lab rats spend countless hours together, helping each other calculate concentrations, prepare new samples, conduct assays and endure the wait to see the latest results. Perhaps better than anyone, they know that the fourth-floor lab in Hashinger Science Center is home to lots and lots of waiting.

So during the downtime, they dive into course work for other classes. Or they review new cancer research literature. Sometimes they brainstorm essay ideas for their grad-school applications. Then there are the occasional escapes into the game “Would You Rather.” Haddad is always the antagonist. “Would you rather only eat tortilla chips or only drink orange soda for the rest of your life?” she asked Shoshan on a recent morning. The questions change, but the choices are never ones Shoshan would favor. Sometimes the options are downright objectionable.

“She knows how to make me laugh,” he says.

Slivers of silliness are welcome in these students’ lives, and not just because their research deals with life-threatening illness. During the summer, much of their time together was spent sharing updates on the fighting in the Middle East that killed 2,200 in the Gaza Strip and southern Israel. Both students have close family members who felt the direct effects of the conflict. And who knows, if they were in their familial homelands right now, they might even view each other as the enemy.

You see, Shoshan is Israeli and Haddad Palestinian.

“Dori and I are more alike than we’re different. And in light of what we’re researching, regional issues become especially trivial. Cancer doesn’t care if you’re Palestinian or Israeli.”

Cultural and geopolitical divisions are never easy to overcome, and in times of extreme pressure they can stretch friendships until they snap. But for Shoshan and Haddad, the bonds of shared purpose outstrip any potential for discord.

“We’re both moderate and open-minded, and we both want peace,” Haddad says.

And they both see the world through the lens of science.

“From a biological perspective, there are more genetic differences within a racial group than there are between two people from different groups,” Haddad says. “So Dori and I are more alike than we’re different. And in light of what we’re researching, regional issues become especially trivial. Cancer doesn’t care if you’re Palestinian or Israeli. We’re doing this research to benefit everyone.”

Cultures Close and Apart

Shoshan was born in the Israeli settlement of Beit Aryeh, beyond the Green Line of demarcation that is still a source of conflict between Israelis and Palestinians. When he was 11, he moved with his family to Las Vegas because his parents had a chance to relocate their business manufacturing doors and windows. His mom and dad both have six brothers and sisters, so Shoshan left behind many aunts, uncles and cousins — just about all of them having some direct connection to war.

“It’s such a small country that if someone dies in a war, chances are someone close to you is related to the person who died,” he says.

Even his mom’s name, Tiranit, was born of conflict. The Straits of Tiran were a key component of the Six-Day War in 1967.

For Haddad, the connections are just as strong. Both of her parents are Palestinian, and though she lived in Los Angeles, she grew up speaking Arabic and had very little contact with American students until her parents enrolled her in a public middle school so she could acclimate to U.S. culture.

Her first day of school, she wore a thobe, or tunic, which identified her as different, and when a boy sat down next to her and began asking questions, she was so startled that she had to excuse herself and leave the class.

“I was used to boys and girls studying separately,” she says.

Still, Haddad and Shoshan both adapted quickly and did well in school, with each developing a strong interest in medicine. Haddad’s father was a doctor, and Shoshan’s grandmother volunteered at a home for special-needs children that provided medical care. The two started volunteering in hospitals and excelled in biology and chemistry classes.

Organic Chemistry

They met as Chapman freshmen in Biology 205: Evolution and Diversity of Multicellular Organisms. They shared time in the class and in the lab, quickly becoming friends, but they didn’t know much about each other’s background until they sat together in organic chemistry. One day as they waited for a lecture to start, the conversation turned to cultural heritage.

Shoshan volunteered that he’s Israeli, and there was a pause. “Oh, wow,” Haddad finally said. Then she offered, “I’m Palestinian.”

“Wow,” Shoshan answered, as the two looked at each other and smiled. The conversation quickly moved on, somehow segueing to the best falafel place each had found and the amazing hummus at Zankou Chicken in Anaheim.

“Honestly, it just isn’t an issue,” says Haddad, who as a Catholic is among the small percentage of non-Muslim Palestinians. “(Our differences) are not something we shy away from; it’s just that we have so many other things in common.”

Both have a passion for science and plan careers in medicine — Shoshan as a physician, Haddad as a pharmacy professional. And they both participated in the Chapman Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) program.

The program allowed them to work directly with a faculty mentor and focus on a cancer research project each helped advance. The chance to learn from research mentors and peers while also concentrating full-time in the lab thrilled the two.

“It was one of the best experiences I’ve ever had,” Haddad says.

A Summer of Surf

Building on research developed by his Chapman mentor, molecular cancer researcher Marco Bisoffi, Ph.D., Shoshan launched a project to target the 30 to 50 percent of prostate cancer cases that go undetected because of false-negative tests at the time of biopsy. There are so many false-negatives because the current method of detection is so hit-and-miss. A limited number of core samples are drawn from the prostate, and if none hits a tumor, the choices for further clinical management are also limited.

So Bisoffi and Shoshan started thinking outside the tumor. They focus instead on surrounding tissue and test for biomarkers as indicators of cancer, circumventing the strict need to detect cancer cells themselves.

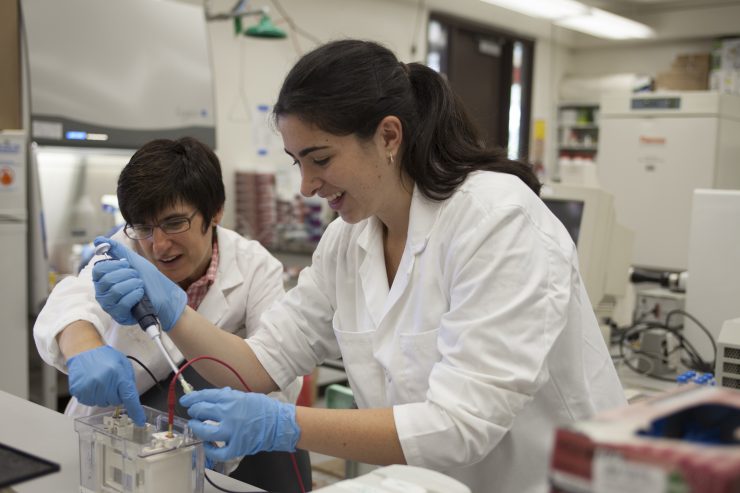

Meanwhile, Haddad is studying the benefits of natural products on inhibiting the growth of pancreatic cancer cells. Her Chapman mentor, molecular biologist Melissa Rowland-Goldsmith, Ph.D., has studied the beneficial effects of a pomegranate juice extract, while others have also looked at other potential inhibitors, such as the caffeine in green or black tea. Haddad decided to test a combination of the therapies.

Both Haddad and Shoshan have compiled encouraging results that they hope will lead to papers in peer-reviewed journals. But for now, they know that there’s still more lab work to do.

What sends a student researcher back into the lab, day after day, knowing that the ultimate reward may be years away or may not come at all? Haddad answers with a singularly beautiful lab memory.

“I was looking at cells under a microscope and noticed there were hardly any of them, and the ones I saw looked dead,” she says. “The treatment I formed caused those cells to die. It took my breath away and I started to shake. It was the most amazing feeling. I wanted to keep coming up with treatments to do terrible things to those cells.”

Professor Rowland-Goldsmith is confident that Haddad will have many more beautiful moments in the lab.

“She knows what she wants, and she isn’t going to let anything get in her way,” she says.

Rowland-Goldsmith saw that drive even before Haddad became her student. Twice Haddad came to her asking to join her lab team, and twice she had to say that she had no openings to offer.

“In the meantime, I suggested that she review the literature, and not only did she read those articles, but she found and reviewed other ones as well,” the professor recalls. “Her maturity is quite fascinating. She’s always one step ahead.”

Likewise, Shoshan is “a student of the utmost talent — skilled, inquisitive and healthily ambitious,” Professor Bisoffi says. “I’m thrilled to have him in the lab.”

Like Haddad, Shoshan can be so meticulous that it borders on the compulsive, he adds.

“If he knows an experiment wasn’t optimal from the beginning, he’ll stop and start it all over again,” Bisoffi says. “He doesn’t accept less than optimal performance.”

Sidestepping Conflict

Shoshan and Haddad share so much lab time and so many traits that sometimes it seems hard to separate them, even for their mentors. And given the Middle East events of this summer, that closeness could have been a concern. When each day brought news of Israeli airstrikes or Palestinian rocket attacks, and media outlets were blowing up with inflammatory rhetoric, there were moments in the lab when Bisoffi thought the conversation might veer into dangerous territory.

“I’ve never been to Palestine, Jordan, Syria, Israel, but I can imagine how polarizing the atmosphere can be,” he says. “Dor and Lena are very smart, and I’m sure that they have opinions. Plus, they’re dealing with the influence of their homes and families. But they realize that the research, by definition, has to overcome these things.

“They choose to be colleagues and friends, and I think that’s a great thing.”

The students’ friendship has endured a multitude of stressors, and next year, as Shoshan heads to medical school and Haddad starts her pharmacy studies, it will

continue. The students are sure of it.

“We’ve been through too much to let it stop once we graduate. I’ve told him repeatedly that when he gets to medical school, he can call anytime with pharmacy questions, and I’m definitely going to call him,” Haddad says.

Perhaps those calls will also touch on politics or world events — perhaps new cancer breakthroughs, or just each one’s latest research into the local falafel scene. One thing Haddad knows for sure: the conversation will flow from a source of mutual admiration.

“Dori has never made me feel anything but respected,” she says. “We’re both Middle Eastern, and we’re passionate people. Luckily we’re passionate about the same thing. We’re both trying to make a difference in the world.”

Photo at top: Lab partners Dori Shoshan ’15 and Lena Haddad ’15 say that their friendship overshadows any conflict in their homelands. “We realize that our research is so much bigger than the two of us,” Shoshan says.

Photos by Nathan Worden ’13 (MBA ’15).

Add comment