Chances are, you’ve done one or more of the following recently.

- Looked at the price of renting or buying near work, shaken your head and opted for more affordable housing farther away, becoming what transportation planners call a super commuter.

- Driven past homeless encampments sprouting alongside freeways or in vacant properties and wished for a solution, while wondering how it got so bad.

- Clicked on a real estate database to see how your home’s value stacks up and been pleasantly surprised, but also fretful. How long can that last?

Welcome to the complicated world of finding and keeping a place to call home. We’re all affected in these challenging times when housing’s availability, affordability and ability to shape regional economies touch every pocketbook.

“It’s hard to overstate the challenges posed by today’s California housing crisis. The average price of buying a house is now 2.5 times the national average, rents are at historic highs, and the state’s homeownership rate is the lowest it’s been since the Second World War. But this crisis is even worse, as it impacts virtually every institution in the state,” says Fred Smoller, Ph.D., an associate professor of political science in the Wilkinson College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences.

Californians are no strangers to the nonstop soundtrack of real estate chatter that comes with living here. But it’s never been quite like this. In some cities, once-prohibited backyard granny flats are getting the green light, in an effort to address the housing shortage by boosting affordable rentals. Chapman researchers find that traditionally tax-averse Orange County residents are willing to pay a tax to help the homeless. Sticker-shock anecdotes pop up in the news. Did you see the one about the burned-out Silicon Valley house selling for $900,000?

Wading into this fray are Chapman University faculty researchers and students from multiple disciplines. These scholars are leading robust community conversations and projects aimed at finding ways to meet the demand for housing now and in the future.

They range from the Chapman University Orange County Annual Survey that measures residents’ attitudes about development, to outreach by attorneys at the Fowler School of Law’s Bette and Wylie Aitken Family Protection Clinic who are helping people clear legal hurdles so they can end cycles of homelessness.

In addition, the Center for Demographics and Policy housed in the School of Communication brings leaders, developers and policymakers together to discuss trends and solutions, while a proposed Real Estate Division in the Hoag Center for Real Estate and Finance will build on the nationally recognized economic and housing forecasts of President Emeritus Jim Doti. Research interests include the impact of tax reform, demographic changes and technology on the real estate industry.

Chapman’s cross-disciplinary approach looks at housing issues through multiple lenses, with a special focus on the University’s home county. Despite rising rents and mortgage costs, Orange County remains a highly desirable place to live, says Smoller, who along with Mike Moodian, Ed.D., conducted the Chapman University Orange County Annual Survey.

“The American dream is alive for many. Seventy percent still want to stay,” Smoller said in a presentation delivered at Chapman’s 2018 Local Government Conference, titled “Will California Ever Figure Out How to House Itself?”

But Smoller and other researchers also sound cautionary notes. Those high housing costs threaten to price out families and highly skilled younger workers needed to fuel job growth. They also push low-wage workers into substandard housing or homelessness and eat up discretionary spending among the middle class. The call to correct that course is a unique opportunity, Presidential Fellow Joel Kotkin said during Chapman’s Infinite Suburbia Conference in February.

“This is a great place to live. There is no better place in the United States than Orange County. How do we build on that?” said Kotkin, who writes about demographic, social and economic trends in the U.S. and internationally. “Because it’s not really reaching its potential.”

Population shifts could change that, said Marshall Toplanksy, co-author with Kotkin of the research brief “Orange County Focus: Forging Our Common Future.”

“The 35-to-49-year-olds are moving to places like Austin, Dallas, Denver, Nashville, Phoenix. This is really an important indicator. We’re losing our seed corn,” Toplansky said.

To reverse this trend, the authors suggest that Orange County transition into a new era powered by small to medium-sized entrepreneurial businesses largely in professional, artistic and technical fields. This transition is already in evidence, says Doti, Ph.D., whose annual Economic Forecasts have a remarkable track record for accuracy.

“We are gaining rapidly in higher-tech jobs and industries. Those are the people who are buying here,” Doti said in a recent housing talk presented to the Chapman University Endowment Council.

While legislators propose policy changes intended to add housing units, as with a recent plan to increase the density of housing near urban transit hubs, Doti counters with a less-is-more perspective.

“The only action that’s really needed is for government to get out of the way and focus its attention on removing costly and burdensome land-use regulations,” he wrote in a recent Orange County Register op-ed.

Yes, housing issues are complicated. But that also creates an ideal opportunity for bringing many creative and thoughtful voices to the conversation.

“These are very serious problems,” Smoller said. “It’s important to have people on the left of the political spectrum and on the right of the political spectrum. It’s important to have people who are committed to government solutions and people who are committed to free-market solutions. We have to listen to everyone.”

Housing Affordability Tops List of Concerns

By Dawn Bonker

Orange County residents see housing affordability as the region’s top problem. What’s more, they are worried that their children won’t be able to afford to live here, and they might be willing to tax themselves to help solve homelessness. Those are among the findings of a comprehensive Chapman University survey seeking to get a read on the attitudes of Orange County residents.

“Fifty percent of our (700) respondents were worried that their kids won’t be able to buy a home in Orange County – any home,” said Fred Smoller, Ph.D., associate professor of political science at Chapman and lead researcher on the Orange County Annual Survey, supported by a grant from Fieldstead and Company.

No wonder. The median price of a home in Orange County reached $725,000 in March, according to real estate data firm CoreLogic. Rents follow suit: The Orange County average was $1,871 in the last quarter of 2017, according to data firm Reis, Inc.

Homelessness was the second-biggest concern on respondents’ radars. A wide majority – 63 percent – said they would support a quarter-cent tax to fight homelessness. However, 70 percent don’t want affordable housing in their neighborhoods, a possible reflection of the debate among community leaders over where to locate shelters and programs for people who are homeless.

The survey threw a light on other trends, as well. Residents support several views typically associated with left-to-moderate perspectives, including gun control, environmental protection and Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), Smoller said.

Attitudes toward climate change especially surprised the researchers, who say that more than 80 percent of survey respondents consider it a major challenge.

“For the first time in our research, because we did a similar poll in 2010, a majority of Orange County residents see climate change as either a somewhat serious or very serious problem, including slightly more than 50 percent of Republicans. Whereas, eight years ago we were talking about ‘Is this even real?’” said Michael A. Moodian, Ed.D., a Chapman integrated education studies faculty member who co-directed the survey.

The political shift and a greater interest in government solutions to social ills were among several eye-opening results in the new Chapman University Orange County Annual Survey. The potential short-term upshots are clear.

“The implications for this are that there will be the real possibility of very competitive congressional elections in November, possibly contributing to a ‘blue wave,’” Smoller said.

But those winds of change could resound long into the future, too, reshaping the county’s identity and mindset, researchers say.

“It’s not that people’s attitudes are changing. It’s that the people themselves are being replaced,” Smoller said, noting that the county is much more ethnically diverse today than it was a generation ago.

A significant signpost from the survey is residents’ attitude about President Trump. Nearly two-thirds disapprove of the job the president is doing, according to the survey results. That’s a reversal of traditional GOP loyalty in the county. In 2004, a similar poll showed that more than half of Orange County residents approved of the Republican then in the Oval Office, President George W. Bush.

Still, while respondents want government to be more involved in solving social ills, they prefer small government, which Smoller describes as the traditional Orange County mindset.

The researchers suggest that such contrasts might connect to the county’s struggle to manage big-city challenges while holding to small-town sensibilities.

“People have it in their head that we’re Mayberry. But the reality is, this is Gotham City,” Smoller said. “If you’re a metropolitan area, you have to build an airport. If you’re a metropolitan area, you have to build jails. If you’re a metropolitan area, you have to deal with homelessness. Those are metropolitan problems.”

Soaring Above the Sprawl

By Dawn Bonker

It may seem trendy to nit-pick the suburbs – too much sprawl, bland architecture and transportation inefficiency, critics say. But the fact is that most Americans pick the suburbs when they’re ready to settle down, raise a family or gain some real estate equity.

Still, is it time to rethink the traditional suburbs so they meet the next generation’s housing needs and desires? Absolutely, said participants at Chapman University’s recent Infinite Suburbia Conference. The future of suburbs and their affordability – a hot subject in California and a timely one throughout the United States – was the focus of the conference hosted by the School of Communication and the Argyros School of Business and Economics at Newport Beach’s Pacific Club.

Participants described a mesh of complications affecting housing today. The first wave of millennials is ready to settle down, but housing prices are skyrocketing. Baby boomers tend to stay put in single-family homes, shrinking availability in desirable neighborhoods. Meanwhile, many workers endure excruciating commutes from remote areas and sacrifice time at home as they chase affordability.

Those market forces and societal needs demand urgent attention from researchers, planners and policymakers, said Joel Kotkin, Chapman Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures. Kotkin opened the conference, which also served as book launch for “Infinite Suburbia,” which he co-edited. The anthology features 52 essays from authors in numerous fields, ranging from design and architecture to health and energy policy.

“We really have to look at suburbia. How do we make it better? How do we make it more environmentally friendly? How do we make it more fair from an equity point of view?” Kotkin said.

Technology and entrepreneurial spirit will help, said Alan M. Berger, a professor of advanced urbanism at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, co-editor of the book and the conference keynote speaker.

In his address, Berger described a futuristic suburbia that will feature smaller homes, a preference for shared vehicle services, autonomous driving, product delivery by drones and digital technologies that make it all happen with touchscreen ease. Among the advantages he listed would be more greenspaces and fewer roads, a combination that can help ease storm runoff and flooding from the more developed areas neighboring the suburbs, he said.

Millennials and those younger, in the so-called Generation Z, will expect suburbia’s traditions of local schools, parks and family life, along with eco-friendly practices, Berger said.

“They do not want the same suburbs we have. They want smart, sufficient, sustainable suburban development,” he said.

Voices

From Chapman’s recent Infinite Suburbia and Local Government conferences.

Steve PonTell

“We need to be able to provide a supply of dwellings. Because it’s a basic – food and shelter is essential. If we as a society cannot do that, we get the consequences we’re having, of which the homeless population is the canary in the coal mine.”

Steve PonTell, president and CEO of National Community Renaissance, a nonprofit builder specializing in affordable housing.

Laura Foote Clark

“We have bad laws. We have tricky zoning and slow permitting. We have a history of red-lining that became our zoning. … We stopped allowing apartments to be built.”

“We have bad laws. We have tricky zoning and slow permitting. We have a history of red-lining that became our zoning. … We stopped allowing apartments to be built.”

Laura Foote Clark, executive director of YIMBY (Yes in My Backyard) Action of San Francisco and the Bay Area.

Jonathan Woetzel

“We think the technology (of robotics) is coming and we will be able to see a whole lot of progress in prefab and modular (home construction). Government needs to be on board with this.”

Jonathan Woetzel, a senior partner and researcher of global business trends for McKinsey & Company.

Mark Stivers

Mark Stivers

“We kind of think housing is affordable when people pay no more than 30 percent of their income for housing costs. We have more than a third of Californians who are paying more than half their (total) income for housing.”

Mark Stivers, executive director of the California Tax Credit Allocation Committee in the State Treasurer’s Office.

Alicia Kurimska ’15

“People are getting priced out, especially in Los Angeles, which has the lowest rate of home ownership in the nation.”

Alicia Kurimska ’15, a research associate at the Center for Opportunity Urbanism and Chapman’s Center for Demographics and Policy.

Karla Lopez del Rio

“Many of our clients are qualified (home buyers). They put down about 15 to 20 offers, and every single time they were outbid by cash investors… If that’s the way our economy is going to grow, then we better come up with something for working families.”

Karla Lopez del Rio, vice president of strategic partnerships at NeighborWorks Orange County, a nonprofit that promotes home ownership.

California Housing: A Study in Art

By Mary Platt

Chapman University’s Hilbert Museum of California Art is a treasure-trove of the state’s history as much as its art. Visitors who admire the museum’s permanent collection of paintings, created by acclaimed artists during the “California Scene” movement, experience a visual trip through time to a period of intense change and development.

The paintings trace the growth of California in the 20th century, from a rural state to the advent of tourism and the growth of major urban centers. As growing industries attracted more and more incomers, housing spread from cramped apartments in cities to lower-density suburban tracts – eventually responding to heavy demand by becoming more expensive wherever it spread. All of it was documented by the observant California Scene painters, whose colorful brushes captured these moments in history for all time.

Millard Sheets, “One Sunday Morning (Chavez Ravine),” 1929, oil on canvas. Permanent Collection, Hilbert Museum of California Art.

Beginning in the early 20th century, Chavez Ravine, on the outskirts of downtown Los Angeles, housed a thriving Mexican-American community where many families lived because of housing discrimination in other parts of the city. It eventually became coveted by the city because of its prime location, and in the 1950s Los Angeles used eminent domain to buy out or force out many of the residents. This culminated in “the Battle of Chavez Ravine” (1951–61) as remaining residents unsuccessfully struggled to retain control of their properties. The site was ultimately conveyed to the Dodgers, and today privately owned Dodger Stadium stands where the community once flourished.

Robert Frame, “View from the Terrace, Santa Barbara, California,” 1970s, oil on canvas. The Hilbert Collection.

Frame returned again and again to the motif of a sea view through a window, or looking outward at the shore and ocean from some beautiful upscale property. “A painting must be a visual adventure,” he said. As more people coveted ocean views, the price of California beach properties rose precipitously. Today, legal battles are waged between wealthy beach-house owners and the public, whose rights to access the state’s beaches have narrowed considerably over the past few decades.

George Post, “Foot of Cumberland Street, San Francisco,” 1974, watercolor. The Hilbert Collection.

Post found the subjects for his bold and creatively composed paintings throughout California, as he traveled and taught art all over the state. Here, he portrays a view of rows of houses stacked back through the San Francisco mist, to a view of the city skyline in the distance. Housing prices in the Bay Area remain the highest in the nation, but because of its higher median household income, San Francisco comes in as the second most unaffordable housing market after Manhattan.

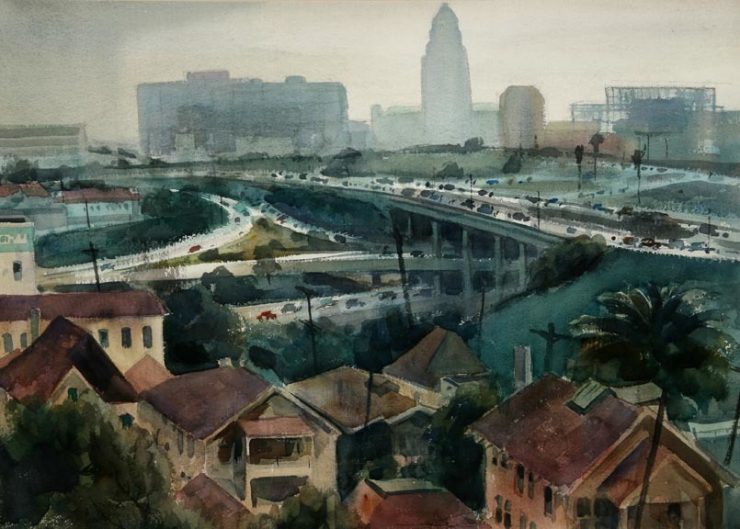

Emil Kosa Jr., “Cloverleaf Confusion,” 1950s, watercolor. The Hilbert Collection.

The advent of the freeway system brought easier access to work and shopping for drivers in Los Angeles and elsewhere, but it came at a price: Freeways often cut through and divided established neighborhoods, bringing noise and pollution to high-density communities. Here, Kosa documents the sculptural aesthetics of L.A.’s innovative Four-Level Interchange, opened in 1953, a marvel of design that includes 22 lanes and seven bridges and is still in use today.

Mary Platt is director of the Hilbert Museum, which opened in 2016 and now is top-rated on Yelp and TripAdvisor. The museum is open 11 a.m.– 5 p.m., Tuesday–Saturday. Admission is free. Visit hilbertmuseum.org.

This story appeared in the spring 2018 issue of Chapman Magazine.

Add comment