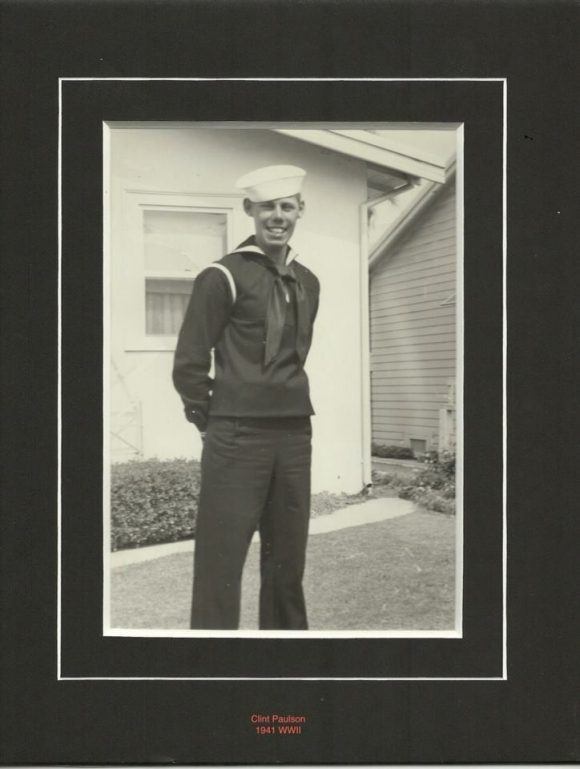

Clint Paulson ’49 can still see in his mind the Los Angeles back yard where he was standing on Dec. 7, 1941. He remembers that he was with his cousin, who was wearing his Army uniform. He recalls details of the radio bulletin he heard, even though the report came from inside a neighbor’s house.

He didn’t realize it at the time, but from that moment forward his life would pretty much divide between what happened before Pearl Harbor and what came after.

About 48 hours later, the Navy called Paulson to active duty, and in short order he was on a ship headed to the Pacific. His ultimate destination was a tiny island he never could have found on a map – a place called Guadalcanal.

“I wasn’t in the original invasion force – if I was, I wouldn’t be talking to you now,” says the Chapman alumnus, now 97. “But I got a taste of the bombing. I was lucky to get through that.”

Even 75 years later, the attack by the Empire of Japan on a U.S. naval base in Hawaii remains a powerful touchstone moment. Beyond the 3,600 killed or wounded, the 188 aircraft destroyed and the 15 ships damaged or sunk, the ripple effects of Pearl Harbor stretch across the landscape of history, affecting countless lives as they also drive perceptions and policy.

“Such a moment almost reflexively pulls you out of a narrow perspective,” says Gregory Daddis, Ph.D., Chapman professor of history and director of the University’s War and Society graduate program. “You have something in common with people you don’t even know.”

Understandably, such an event prompts strong emotions. But it’s vital that those who come later “think deeply about how acts of war can cause unintended consequences,” Daddis adds.

“The Next Bomb May Be Our Last”

As the attack on Pearl Harbor unfolded 75 years ago, Ensign William Czako was inside the USS New Orleans, writing a letter to his sister. His reflections exemplify the historical insights available in Chapman’s Center for American War Letters.

As the 75th anniversary of Pearl Harbor approached, we sought out the voices of those who could provide perspective on the milestone moment, including Daddis, a retired Army colonel who served in Iraq and taught at West Point, and Alexander Bay, Ph.D., a Chapman history professor whose research and teaching focus on Japan.

For most Americans, the attack marks the start of World War II – and for service members like Paulson, it certainly was. But what came before also is important, Daddis says, citing U.S. intervention in the Japanese sphere dating to the mid-1800s and pre-WWII economic policies intended to strangle Japan.

“When we see these seminal events like Pearl Harbor simply as unprovoked attacks by a savage enemy, I think it’s probably worthwhile to do some soul-searching and consider how U.S. policies might have been a factor,” Daddis says.

How the attack is viewed in Japan today depends on who you ask, Bay says. There’s the widespread realization that it woke a sleeping giant – a concern that even plays out in historical records of Japanese cabinet meetings leading up to December 1941.

“In one of the notes, the emperor asks someone in the military, ‘If we declare war on America, how long before we achieve victory?’” Bay says. “The answer was, ‘In under six months.’ So the emperor responds, ‘That’s the same thing you said about the China War,’ which at that point had been going on for three years. I think the muted response was then, ‘But emperor, China is so big.’ It’s at that point the emperor says, ‘You think the Pacific Ocean is any smaller?’”

Despite the emperor’s reservations, the impetus for attack was strong, with its inspiration traceable to the 1904-05 Russo-Japanese War, Bay says. In the Battle of Tsushima Strait, Japan’s stunning naval attack led Russia to accept peace terms brokered by Theodore Roosevelt.

“This was the reigning paradigm for the attack on Pearl Harbor,” Bay says. “In Japan’s experience, wars are won with big, decisive naval battles that knock out a fleet, then you sue for peace.”

Life Behind Barbed Wire

For Toshi Ito ’46 and Paul Nagano ’42, the days after Pearl Harbor brought internment in relocation camps. Their memories remain vivid, and their insights particularly relevant, given the post-election talk of a possible Muslim-American registry.

These days in Tokyo, there are strong factions that seek to revive the nationalist fervor of such military triumphs, Bay notes. In recent years, the right-leaning administration of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has sought, with some success, to reinterpret Article 9 of its post-war constitution, which precludes Japan from using military force.

“In the last election, they got enough votes in the upper house to go forward with constitutional revision, but how far they go with it will be a public PR issue,” Bay says. “They may be a little careful for fear of a public backlash.”

Still, Japanese connections to Pearl Harbor are probably strongest in revisionist-history circles “that take pride in a time when Japan took the fight to the enemy,” Bay adds.

And how do U.S. officials feel about Tokyo taking steps toward a return to a full-fledged military?

“I think they welcome it,” Bay says. “We’re looking for people to support our various overseas engagements. My sense is that as long as the China threat looms large over Japan, they will be very happy we’re there and have their back. And we are very happy they are there and have our back.”

Nationalist zeal isn’t isolated to Japan, of course, with evidence as close as the U.S. election. Many Americans are now weary of war while also longing for the supremacy that military might can produce.

“Part of the problem we see, not just in the political campaign today, is that hyper-nationalism narrows your field of view – your sense of appreciation for the larger world,” Daddis says.

In this regard, Daddis sees parallels between Pearl Harbor and 9/11.

“We want to use these traumatic events as something to rally around,” he says, “and in the process it becomes difficult to question the policies that led up to them, because to do so is to be unpatriotic.”

Pearl Harbor and 9/11 are also similar in that those who planned them didn’t foresee the prodigious response headed their way, Daddis adds. Likewise, both attacks solidified the “special relationship” between the U.S. and Britain.

It’s no secret that Winston Churchill viewed Pearl Harbor as his nation’s salvation.

“No American will think it wrong of me if I proclaim that to have the United States on our side was to be the greatest joy,” Churchill writes in his history of WWII, reflecting on his feelings after speaking with President Franklin Roosevelt the day of the attack.

“Being saturated and satiated with emotion and sensation,” Churchill continues, “I went to bed and slept the sleep of the saved and thankful.”

Like Churchill, Clint Paulson would have to endure many sleepless nights before the joy of victory would be realized. He spent 19 months as a signalman on Guadalcanal and then was assigned to an AKA attack ship that took him to the Philippines and New Guinea. After four years in the Navy, he had enough points for a discharge. Two days before he got back to Los Angeles, the U.S. dropped the bomb on Hiroshima, hastening the end of the war.

In 1945, Paulson started at Chapman, living in a Quonset hut on the L.A. campus. There he studied sociology toward a professional goal of reducing juvenile delinquency. After a long and rewarding career in education, he retired to Northern California, where he lives with his wife, Jo.

Seventy-five years after the life-changing events at Pearl Harbor, memories of his wartime service remain strong and vivid. For instance, Paulson recalls that after U.S. forces gained control of Guadalcanal, one day he stood on a pier next to a Japanese prisoner who had been brought into American custody. As a small group waited for a transport vessel to arrive, an American officer motioned to the flurry of U.S. activity and asked the POW, “What do you think of all this?”

Paulson recalls that the Japanese soldier looked out beyond the dock to where American warships stretched clear to the horizon. “This,” the prisoner said, “is what we didn’t realize.”

(Display image at top: Smoke from its onboard fires obscures the USS Arizona, which sank as a result of the Pearl Harbor attack.)

Add comment