As director of Chapman’s Center for American War Letters, Andrew Carroll often receives the front-line writings of service members with interesting back stories of their own. For instance, a copy of the letter that follows was found stuffed inside a headboard at a Seattle-area home, generations after it was written. Penned by an ensign while his ship was at the center of the Pearl Harbor attack, the letter “gets to the heart of our project,” says Carroll, an author and historian. “We’re trying to capture history through the eyes of those in the eye of the storm.” William Czako wrote to his sister, Helen, from inside the USS New Orleans even as hundreds of Japanese planes bombarded the U.S. Pacific Fleet. Here are edited excerpts from his letter.

Dear Sis:

It is now 9:05 Sunday morning and we’ve been bombed now for over an hour. Our anti-aircraft guns are yammering and every so often a bomb strikes so close as to rock the ship. Again a bomb. We’re helpless down here in the Forward Engine Room because our main engines are all tore down. We’re trying to get underway if possible. We were just struck by a bomb near the bow. We’re fighting back as much as possible because we have no power to load our guns, no power circuits to fire them. It is all being done by hand.

This seems to you like a nonchalant letter, but it’s the straight dope. There are only a handful of us down here as most of our men are ashore on liberty. They really caught us sleeping this time. Those bombs are getting closer – God grant that they do not hit that loaded oil tanker that is lying right across from us. Ten million gallons of fuel would bathe this ship in an inferno of fire. I am on the interior communications telephone and I can hear the various stations screaming orders at one another. A man just brought us our gas masks. Wave after wave of bombers must be coming. We’ve been struck several times now but fortunately there are no casualties yet.

The next bomb may be our last but I will keep writing until I am told to stop or am given another job. Strangely Sis, I’m not excited but my heart is beating a little faster from all that firing. I don’t know why I am writing this because if we are hit with a bomb here – they won’t find enough of me and the rest, let alone this letter. I imagine it is to show myself that I can be calm under fire. A few of the boys here are white-faced and their voices hushed and choked. They too know that this is no joke or mock battle but the real stuff. For out of a cloud-studded blue sky on a Sabbath morning death comes riding unheralded to claim for its own the unprepared and unbelieving. Who thought that they would strike in such a manner when most men were ashore and spending their payday on those traditional Saturday night sprees? They would not dare to attack us, let alone Pearl Harbor, the mightiest and most fortified base in the world. They could not get within a thousand miles of this place before we’d know it – no they dare not, but they did. Ah, there was one explosion – perilously close. Yes, we were hit but not badly. The bomb struck between the bow and stern of another ship tied up just ahead of us.

There is another lull and only sporadic bursts from our pom-poms. Preparations to get underway are still continuing. It seems impossible with all that machinery tore up, but still we’ll do what we can. The order has come now to secure from general quarters. We were under fire for nearly two hours and I’m going to sneak up topside to see what happened.

Ensign William Czako survived the attack on Pearl Harbor and went on to fight in the Pacific. Because of censorship rules, he had to hold onto his letter for a year before he was allowed to mail it. After the war, he remained in the Navy, working at a shipyard in Norfolk, Va., for more than 30 years.

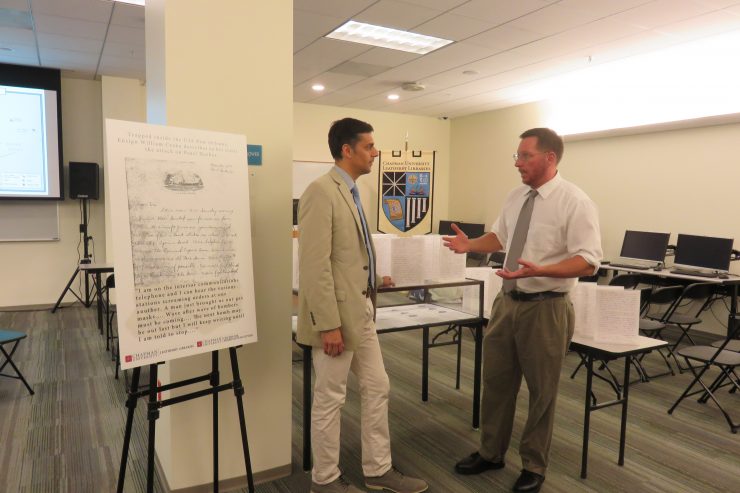

(Image at top: Chapman historians Gregory Daddis, left, and Andrew Carroll converse next to a replica display of ensign Willam Czako’s letter, which is in the archive of the Chapman Center for American War Letters.)

Add comment