In 1941, Paul Nagano ’42 was a student at Chapman, enjoying pranks with his fraternity brothers, studying theology and playing basketball on a team made up of those “too short to play varsity,” he says.

Meanwhile, Toshi (Nagamori) Ito ’46 was a senior at John Marshall High School in Los Angeles, enjoying swing dancing and roller skating when her study schedule allowed.

For Nagano and Ito, the carefree lives they had known quickly ended when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941 – 75 years ago this December. Ito was sewing a dress for Christmas when she heard a radio report of the attack. She ran to tell her parents, who were as surprised as she was to hear the news. The next day, Ito went to school, where she and her Japanese American classmates ate lunch separately, away from the other students.

“We huddled together; we were so embarrassed,” Ito recalls. “It was a very trying day.”

Ito’s father worked for an insurance company, and on Wednesdays he would give a ride to a neighbor, who worked in the same office. On the Tuesday after the Pearl Harbor attack, the neighbor came by to tell him that she would no longer share a ride with a “Jap.”

“We had no idea how quickly we would become the hated enemy,” Ito says.

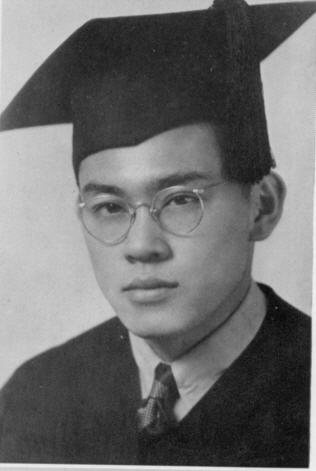

Paul Nagano ’42, seen in his CEER yearbook photo, didn’t get a chance to attend his Chapman graduation but instead received his diploma at the Arizona internment camp where he and his family were incarcerated.

Within months of the attack, both Nagano and Ito were incarcerated in relocation camps with their families and thousands of others – Nagano in Arizona and Ito in Wyoming. For Nagano, presidential Executive Order 9066 meant an early end to his senior year at Chapman — no grad week antics with friends, no place in the traditional commencement procession. But deep in the Arizona desert where Nagano and his family were interned, a package arrived – Nagano’s diploma from Chapman.

“I received my bachelor of arts degree, sent to me in the wilderness camp. It was a total surprise, but meant a great deal for me to be remembered,” he recalled a year ago.

In 2015, the Rev. Nagano, Ph.D., was remembered again by his alma mater when he was presented an honorary doctorate at the commencement ceremony for Wilkinson College of Humanities and Social Sciences. It was his first visit to the Orange campus, as he attended Chapman when it was in Los Angeles.

“It’s a redemptive experience, because you know to have your education interrupted and go into a concentration camp, it’s kind of disappointing,” Nagano said, speaking from Atherton Baptist Homes in Alhambra, where he resides and serves as a chaplain.

The Rev. Nagano, Ph.D., says that receiving an honorary doctorate from Chapman in 2015 was “a redemptive experience.”

Disappointment is about the harshest word Nagano has for the internment experience that interrupted the lives of nearly 120,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans. He recalls tense moments in the days after Pearl Harbor, including a scuffle in a diner with an angry man who called him “a damn Jap,” as well as detainment by police when he was visiting two Baptist missions he served in Japanese neighborhoods near Los Angeles Harbor and Terminal Island. By spring he was in Poston internment camp. But he says his faith, work and even the process of writing his doctoral dissertation helped him rebuild and mend his life.

“Because I was in service to God, I was able to handle it,” he said.

Nagano was allowed to leave the camp to attend

Bethel Baptist

Seminary in Minnesota so he could enlist in the Army as a chaplain, but the war ended before he completed his degree. After finishing the degree, he went on to a successful career in ministry, serving congregations in Los Angeles, Hawaii, Seattle, Oakland and throughout Northern California.

He earned his doctorate at the

Claremont School of Theology

. There Nagano says he spent a year of intense study on the subject of race, ethnicity and identity. The process helped him resolve the questions that “haunted” him after the war and internment, he says.

“In our world we have to learn to live with diversity,” Nagano said. “In this diversity, life becomes much more interesting and exciting. Not only interracial, but interfaith, too.”

For Ito, early 1942 should have been her own exciting time. She was a recent high school graduate, but she had no chance to celebrate or even look for a job or a college; she and her family were sent first to a makeshift detention center at the Santa Anita Racetrack in Arcadia, Calif., and then to the Heart Mountain Relocation Center near Cody, Wyo.

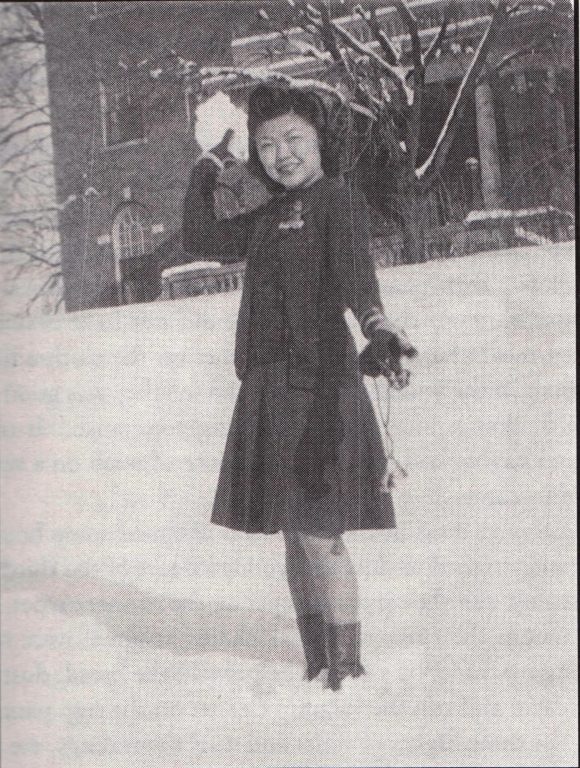

It was a happy moment in 1942 when Toshi Ito ’46 was allowed to leave the internment camp in Wyoming and attend National College in Kansas City.

Ito recalls in her 2009 book

Memoirs of Toshi Ito

that the first arrivals at Santa Anita were housed in horse stalls, and the stench was horrible. Her family’s four-day rail journey to Wyoming was “a dismal trip in a dismal environment,” she writes.

At Heart Mountain, her family and about 10,000 other dispossessed people were surrounded by barbed wire. They struggled to adapt, especially during a winter in which the temperature dropped well below zero, she says.

Internees eventually established a reasonable semblance of everyday life and work, setting up their own newspaper, farm and gardens, healthcare system, education system, sports, hobby groups and religious groups. As the war continued and restrictions eased, internees were given opportunities to move from the camp to work locally or go to college in the Midwest or the East.

Ito attended National College in Kansas City, Mo., for a while, and met and married James Ito, a fellow internee and assistant farm superintendent at Heart Mountain. With the end of the war in 1945, internees were allowed to leave Heart Mountain and the other camps and return to their homes, finally bringing to an end a particularly dark and disturbing episode in American history: when America forced some of its own citizens, selected by race alone, to live in what were essentially concentration camps.

Returning to California, Ito wanted to continue her college education, but found many doors still closed to her because she was of Japanese ancestry. However, when she applied to Chapman, then located in Los Angeles, she found a place that felt like home.

“I felt so welcome, so accepted,” Ito says of her time at Chapman, which honored her last year during an event that included a screening of the award-winning documentary “The Legacy of Heart Mountain.”

“I felt so welcome, so accepted there,” Ito said a year ago, when she visited the Chapman campus in Orange for a screening of the Emmy-winning documentary

The Legacy of Heart Mountain.

She graduated from Chapman in 1946, and when she got her degree in sociology, she was joined by nine others in her graduating class. Ito went on to teach kindergarten and second grade for 26 years at Elysian Heights Elementary School in Los Angeles. In addition, she has been active as a board member of the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation, which runs the

Heart Mountain Interpretive Center

, seeking to preserve and pass on the Heart Mountain story to future generations. One of her children is the Honorable Lance Ito, the judge who is best-known for presiding over the O.J. Simpson trial.

When she thinks back on the days after Pearl Harbor and her family’s internment, Ito is flooded with thoughts of “a sad time — an embarrassing time,” she says. And now, as she reads about how the transition team for President-Elect Donald Trump is considering a registry for immigrants and visitors from Muslim countries, she and other Japanese Americans are “trying real hard to prevent Muslim Americans from being incarcerated without due process of the law,” she says.

She and some colleagues on the Heart Mountain foundation board are suggesting that the president-elect visit the internment site so that mistakes of the past aren’t repeated.

“We sure don’t want to see that happen again,” she says.

Add comment