Michael Tesauro (M.A..MFA ’15)

Before the terrorist attack that killed 14 people Dec. 2, San Bernardino, where I grew up, was already famous for violent crime. Shootings came in three categories: gang-related, drug-related or police-related. Sirens were as commonplace as barking dogs and mailboxes.

The violence is why people leave. I moved to neighboring Redlands hoping to escape. And so I wound up living nine doors down from the townhome rented by Syed Rizwan Farook and Tashfeen Malik, the San Bernardino shooters. I walked my dogs by the place but don’t remember ever seeing them. On the day of the shooting, I stayed inside and listened to my hometown next door become a worldwide talking point for the first time in my life.

Within hours, MRAPs – military-grade mine-resistant vehicles – were circling my neighborhood. Helicopters were overhead. San Bernardino had come back to me. By night I was locked down, and by Thursday morning the area was a federal investigation site.

Two days after the massacre, the police tape had been taken down. I could move freely, so I chose to go see my neighbor’s house in person. Watching news crews crawl through the shooters’ realm was a perfect crystallization of how fast the media eye flickers. This was a “better story” than the office-party carnage – here were a driver’s license and baby toys and prayer mats and ammunition.

Growing up in San Bernardino, you live in a radius of violence, so you come to expect horror being within walking distance.

In Redlands I live amidst all kinds of people from all kinds of places. I am good friends with a Tunisian family a few doors down. A single father lives across the street; we have different views on politics, but we get along because we’re both young. That is more or less my social circle. I don’t know most of my neighbors because they are ever-changing.

We live near the headquarters of ESRI – a global mapping company, which often brings in employees on H-1B visas. They and their families will rent a home close by, work for a time, and eventually leave. On my block the new Muslim family does not cause a stir. Many ESRI employees are of South Asian or North African descent. Seeing men and women in traditional garb is not new or different. This is why Farook and Malik fit in.

The Thursday immediately following the shooting, an L.A. news anchor asked me, “How does that make you feel that they were right there? That they had bombs?” My answer was along the lines of, “That’s the world we live in, I guess.” I saw a clear disappointment in his face. While I know his job is to perpetuate a version of the news that makes people shudder in fear, I couldn’t give the reaction he wanted.

I did feel disturbed when it was revealed that Farook and Malik had concocted nebulous plans involving schools. My mother was a principal in San Bernardino, and they had looked at her school and others. I do indeed fear the terrorist next door, but there were all kinds of terrors in San Bernardino, and a terrorist is more likely to look like me (a guy with fair skin and brown hair) than like Farook or Malik.

For a too-brief moment, my hometown – finally – was the focal point of intersecting conversations about gun control and violent crimes. And then, quickly, the story veered toward terrorism. That’s understandable, but heartbreaking. San Bernardino’s other problems are put on mute.

I ask myself where the calls for prayer and the assertive Facebook posts were prior to the Inland Regional Center shooting, the darkest moment of a tragedy that has been going on for a long time, in slow motion.

Michael Tesauro (M.A./MFA ’15) is a writer and professor. A version of this story originally appeared on

Zocalo Public Square.

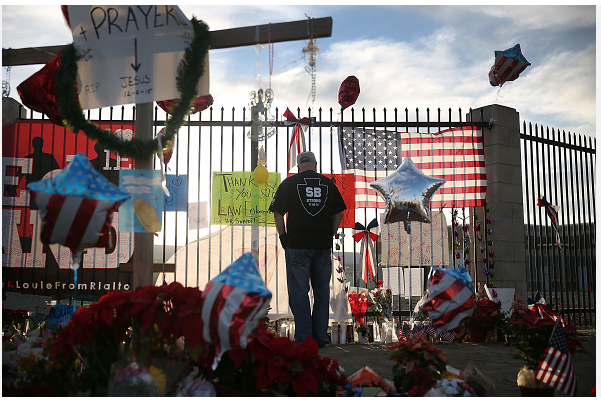

Top image: A man stands by a make shift memorial near the Inland Regional Center in San Bernardino, California. Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images.

Add comment