Raise your hand if you ever read a comic book as a kid. For many readers (and this writer), comics arrive in the form of youthful allowance money well-spent.

Today, the comic book stories and graphic novels of our childhoods are getting, well, the hero treatment, rising from thin, cheap colorful pages to now occupy the big screen, video games, conventions and major retailers. According to estimates by the trade news sites ICV2 and Comichron, North American comics and graphic novels generated sales of $935 million in 2014, roughly double the annual figure just a decade ago.

Once thought of as simple entertainment for children, graphic fiction has also progressed, panel by panel, to become a serious literary force in the classroom. Classics such as

The Watchmen, Sin City, Blade

and

V for Vendetta

have all made the leap from page to screen to critical acclaim.

Wham! Pow!

Spark: a Chapman story

This summer, the editors of Chapman Magazine took a risk and transformed the summer issue into a work of graphic fiction. This special Chapman Now issue, called Spark, tells the story of three students who travel to the future, face a challenge and respond with creativity. Share your thoughts on the issue by emailing magazine@chapman.edu.

Wait, aren’t comics and graphic novels the same thing?

No. And yes.

Each uses illustrated panels to tell a story visually, and graphic novels come from the world of comics. However, length and content are what primarily separate the two, says Bryce Carlson ’07, managing editor at the comic publishing company

Boom! Studios

. Longer stories told in a single piece are usually considered graphic novels, whereas traditional-format comic books tend to feature a quick, action-packed tale.

Carlson himself has written graphic fiction and is the author of

Hit,

a crime neo-noir series telling the stories of detectives in 1950s Los Angeles. Its more serious tone lends itself to the graphic novel format. However, it started off as a short-series comic, and was then collected into a long-form graphic novel.

Carlson said this trend is common in the industry: Test the waters with the original run, then “collect” the works into one book. But some stories, Carlson says, are clear shots for one or the other publication style.

“It all comes down to the story,” Carlson said. “With graphic novels, you can be a little more patient; with monthly comics, you have only maybe 20 pages.”

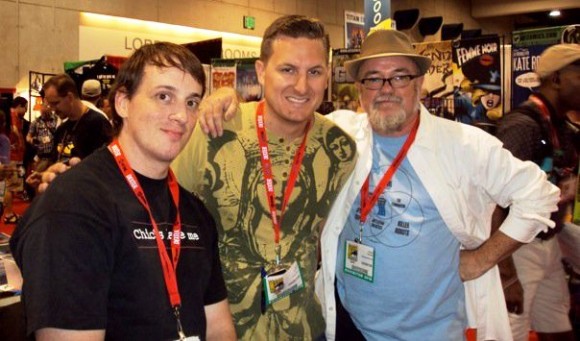

From left: Artist Tony Parker, Boom! Studios managing editor Bryce Carlson ’07 and writer-letterer Richard Starkings share a moment at Comic-Con. Carlson works in the world of comics and graphic novels as a writer and editor.

There’s lots of evidence that graphic novels and comic books are maturing as a genre. For instance, both are growing in their embrace of diversity: the new Ms. Marvel is Muslim; the new Spiderman Peter Parker character, named Miles Morales, is bi-racial; and the new Thor is a woman.

With that inclusiveness in mind, graphic literature is now helping mere mortals with a superhuman task: The college course syllabus.

High-level, not low-brow

“I’ve always viewed comics as a high form of literature, not just kid stuff,” says Chapman adjunct professor

David Winnick (M.A./MFA ’09)

.

Also a Chapman graduate, Winnick teaches English 103: Pop Culture Graphic Novel and Comic Book in addition to writing comic fiction. For his classes, comics are a teaching tool that allows students to literally see the form of the story.

Comics also extend the tradition of fables and myths, he adds.

“Most of those myths and fables are parables; (they are) there to teach a lesson … be respectful of elders, be a good member of your community, don’t lie, don’t cheat, don’t steal,” Winnick said. Stories in graphic fiction, especially superhero stories, often follow that lead.

Students in the class often ask if they will read

V for Vendetta,

a classic graphic novel. He responds by asking what the students know about the British political climate under Margaret Thatcher, because

Vendetta

isn’t just a cult read with an interesting plot; it’s a social commentary on 1980s British conservative politics.

Winnick isn’t the only one at Chapman to use graphic fiction to feed discussions about complex topics. Professor

C.K. Magliola

uses a variety of graphic novels in her anthropology and sociology coursework.

Professor C.K. Magliola uses the Pulitzer Prize-winning

Maus

by Art Spiegelman in her coursework.

Maus

tells the story of Spiegelman’s father surviving the Holocaust in Poland, with the characters drawn as mice.

“I think there are ways that graphic novels bring subjects to life that regular materials can’t,” Magliola said. “It allows (students) another way to connect to the tragedy — it allows a new way to enter into these issues.”

Magliola said the way the Holocaust is presented through the graphic novel strikes a chord with students, who sometimes think they already know enough about that chapter in history. Seeing it in a graphic novel changes their approach.

“You’re not just dealing with text – it’s the relationship with pictures. It’s visual, and that makes it so much more emotional,” Magliola said.

Magliola admits that when she first read

Maus,

a widely hailed graphic novel set amid the Holocaust

,

she cried

.

Why so serious?

Tough topics and thought-provoking content are a hallmark of graphic novels today. Carlson credits the genre split from the short comic format to longer graphic novels with a backlash against the Comics Code Authority, established in 1954 as a way to regulate comic book content.

Rather than conform, some creators of comics began to self-publish or launch independent imprints such as Underground Comix. The tumultuous world of the American 1960s saw the comics genre become a medium for more highly developed social messages, but comic literature was still in its infancy.

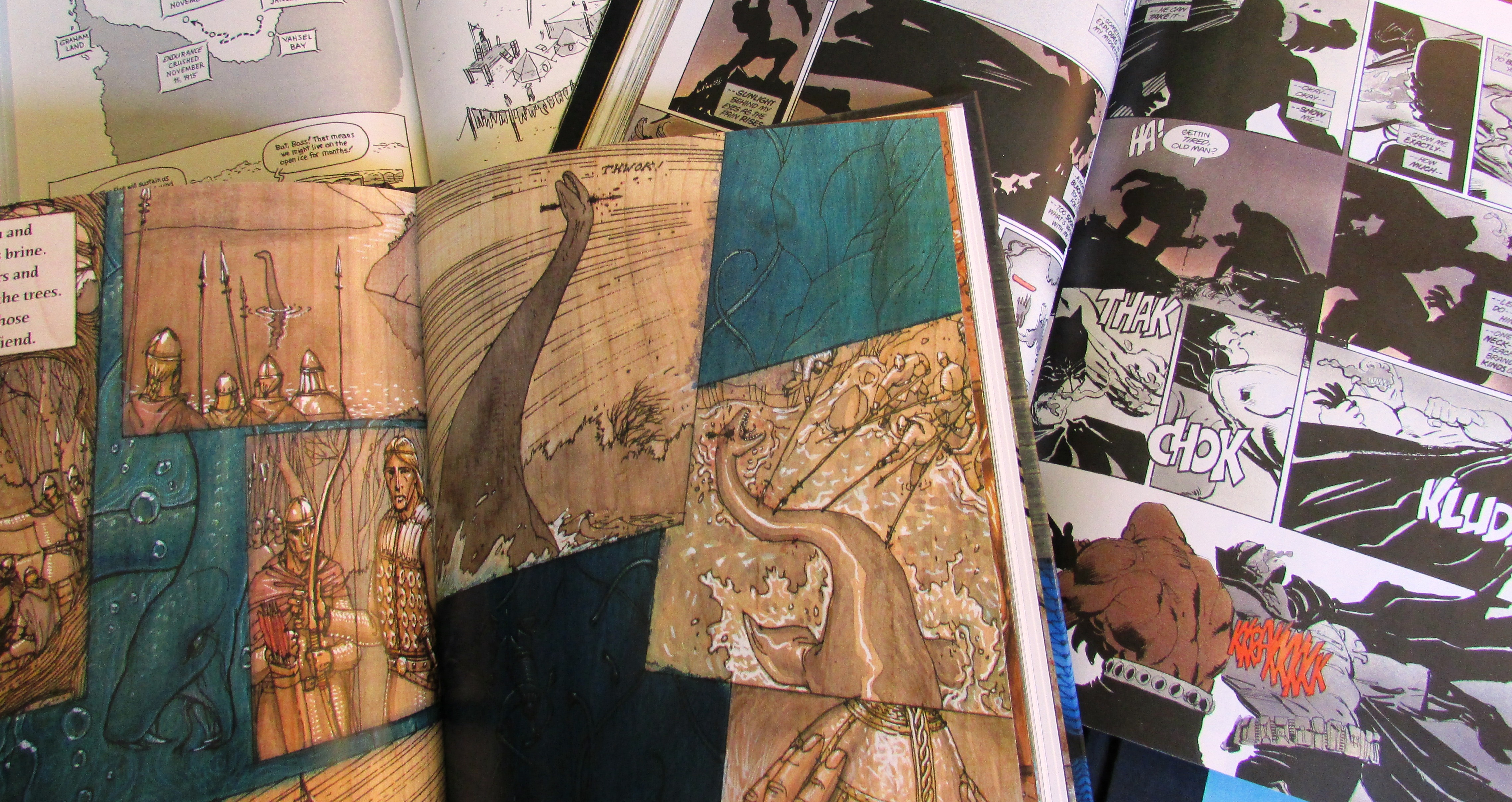

Reader’s Choices

Chapman University’s Leatherby Libraries features a growing collection of graphic novels. If you’re just getting started on the graphic novel canon, here are a few suggestions:

- Maus, by Art Spiegelman, tells the story of the author’s father surviving the Holocaust in Poland.

- Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, by Frank Miller, conveys intertwining stories of Batman and superheroes through a lens of grit and crime.

- Sin City, also by Miller, spawned a sci-fi fantasy series that pretty much defines the term “hard-boiled.”

- Persepolis, by Marjane Satrapi, is a coming-of-age memoir set in Tehran during the Islamic Revolution.

- V for Vendetta, by Alan Moore (author) and David Lloyd (illustrator), blurs the lines of good and evil.

“I feel like a lot of it happened with counter-culture. … The ’70s is when comics really started having something to say,” Carlson noted. “That’s when comics started broaching the subjects of race, guns, violence, and tying it into the socio-political themes of the times.”

Carlson said these publications only continued to get grittier in the 1980s, which is when the genre started gaining more visibility. This was the turning point for many to see comics as literature — serious topics, serious audiences and serious recognition.

People started seeing that “comics are not just superhero stories … comics are not just a genre,” Carlson said. “Graphic fiction is its own medium, like TV or prose, and there are things you can do in graphic fiction you cannot do in these other ones.”

That realization is what Carlson says is so refreshing about graphic fiction – it can be and do anything.

Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic is not to be missed. The Broadway adaptation of her memoir won several Tony’s this year. Our library has a good selection of graphic novels on the first floor.

Yes, Jan — and on that note: http://www.dukechronicle.com/article/2015/08/freshmen-skipping-fun-home-for-moral-reasons and https://today.duke.edu/2015/04/summerreading2019

“It has the potential to start many arguments and

conversations, which, in my opinion, is an integral component of a liberal arts

education.” 😉

Nice comments, C.K.! 😉

-smiley