While the processing of cow milk may help it last longer in your fridge, it can impact the nutritional value of dairy products, Chapman University researchers have found.

Widely used industrial processing methods can affect a component of milk that could be critical for healing, bone health and intestinal disorders. This type of research is significant for the health of Americans, who consume annually more than 650 pounds of dairy per person, according to 2022 government data.

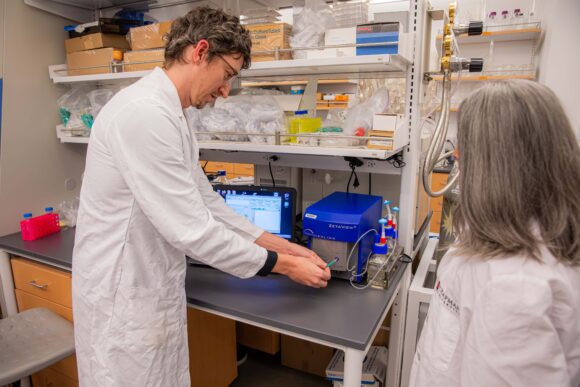

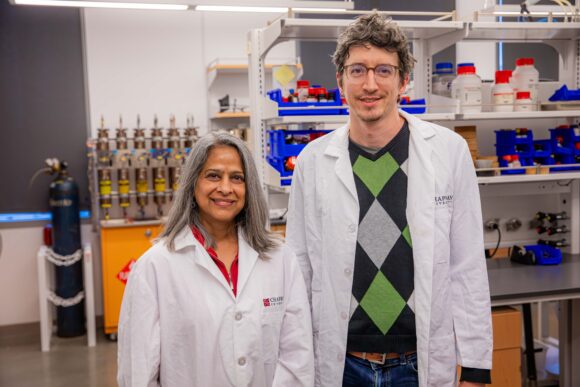

Professors Anuradha Prakash, John Miklavcic and then-student researcher Anna Colella (MS ’21) are interested in the impact of processing on the nutritional value of milk and the way in which it could impact developing babies. About 70% of formula consumed by infants in the U.S. is based on cow’s milk.

“Babies who get human milk are getting a lot of health benefits,” Miklavcic said. “But formula is lacking in comparison, and that could be due to processing methods.”

Impact on Infants

Miklavcic, an expert on the nutritional needs of infants, said that while human milk is the gold standard for the growth and development of children, many babies need to rely on formulas due to a number of factors, including mothers who work or cannot lactate. Cow milk-based formula is an alternative for infants who are not breastfed.

“So when we have to feed the alternative infant formula, the idea is to model it almost as much as possible after human milk,” Miklavcic said. “We’ve done more or less a decent job and babies can grow and still thrive consuming formula instead of milk. But we are still learning a lot more about the differences between cow and human milk.”

One of the critical differences is the presence of extracellular vesicles, which are particles released from cells that may impact the development and maturation of the immune system. The vesicles are more abundant in human milk rather than cow milk. In fact, infants consuming human milk are receiving a lot of these vesicles while there’s almost “next to none” in formula.

The culprit seems to be that the processing methods for commercial cow milk damage the vesicles. The researchers found that processes like homogenization and heat treatments reduced the amount of vesicles between 60% to 90%.

“We need to process milk to make dairy products safe for consumers,” Miklavcic said. “But in doing so we drastically reduce the content of these extracellular vesicles, which might be critical to the developmental processes and short- and long-term health of developing children.”

Colella, who works at See’s Candies as a manager of research and development, said that processing is an important part of producing milk for wide consumption. Consumers generally prefer milk that doesn’t separate and has a longer shelf life. Raw milk can spoil in just a few days.

“It’s not that the industry is destroying it, there are pros and cons,” Colella said. “You’re delivering something that customers desire but the cons would be that these vesicles and other nutritional components can be affected during processing.”

Better Methods

The findings of the Chapman researchers can be used to develop effective processing methods that don’t decrease the nutritional value of dairy products. While further study is needed, Miklavcic suggested that researchers could evaluate potentially adding extracellular vesicles to cow milk formula after homogenization or heat processing to ensure that infants are receiving the nutrients they need.

“Can we get extracellular vesicles from another source and add it to the formula after?” he said. “So it would be safe but more rounded in terms of its nutritional and bioactive content. This research is informing new product development and it’s aimed at improving infant formulas that are going to be manufactured and sold, all with the intent of better meeting a baby’s growth and developmental needs to set them up to thrive.”

The Chapman study could also help widen research into the presence of extracellular vesicles in other foods. Colella mentioned that it would be beneficial for scientists to probe into the presence of “vesicle-like structures” in other foods people regularly consume.

“We don’t know everything about how these structures may impact human nutrition, so there’s a lot of opportunities for evaluation,” she said.

Healthier Future

In addition to potentially contributing to healthier dairy products, the Chapman study also sets an example for future collaboration between food science and nutrition researchers. These two disciplines have tended to be siloed despite their clear connection.

Food science tends to deal with everything that is done to food from the farm to the dinner plate, including agriculture and food processing. Nutrition is what happens to food in the body after it is consumed. The work of the scientists and researchers in these fields is the driver that will promote positive change in the overall health of the country, so it’s important for individuals in these fields to work together.

“It speaks volumes to what needs to happen with health, food and nutrition initiatives in the U.S. and beyond,” Miklavcic said. “The connection surprisingly doesn’t happen organically but it really needs to. We need to know how what we are consuming affects our health, not just for babies, but throughout the lifespan.”

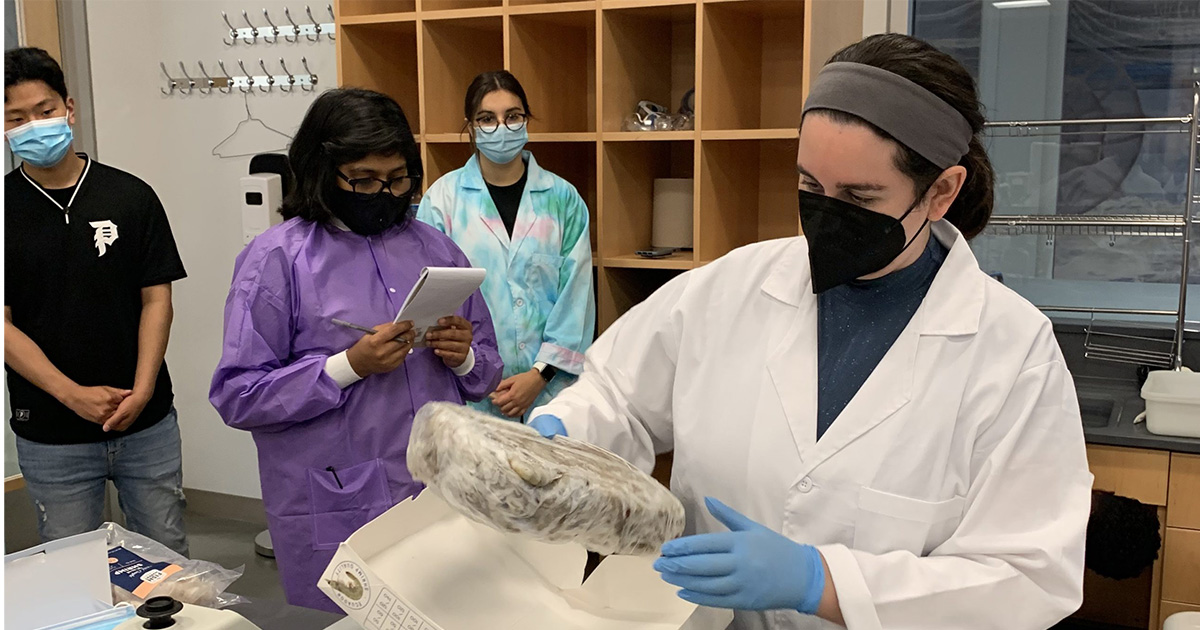

Chapman is particularly situated to lead as an example of collaboration because the university’s programs are less isolated. Food science students are provided with a holistic education and an awareness of the responsibility they have as leaders in the food industry. With the health of their communities at stake, they are passionate about developing innovative ways to deliver sustainable and nutritious foods.

“When our students go out into the food industry, they understand that the foods they’ve created or processed have an impact on the nutrition of the country,” Prakash said. “They want to contribute to a healthier future for their community.”