A shopper grabbing a bag of frozen shrimp may not think to question the label or weight before tossing it into stir fry or shrimp scampi.

Yet, the weight and type of shrimp they buy may not be what the label says, according to a Chapman University professor.

Associate Professor Rosalee Hellberg and some students found in a new study that more than a third of 106 frozen shrimp samples from Orange County stores were mislabeled and/or weighed less than the packages stated. One fourth of samples were glazed with too much ice, and around a fifth were a different species than labels advertised. Among shrimp in the super/extra colossal size category, half of samples were short-weighted.

“When you combine all the labeling errors, that is a relatively high percentage for seafood products,” says Hellberg, associate director of the food science program at Schmid College of Science and Technology.

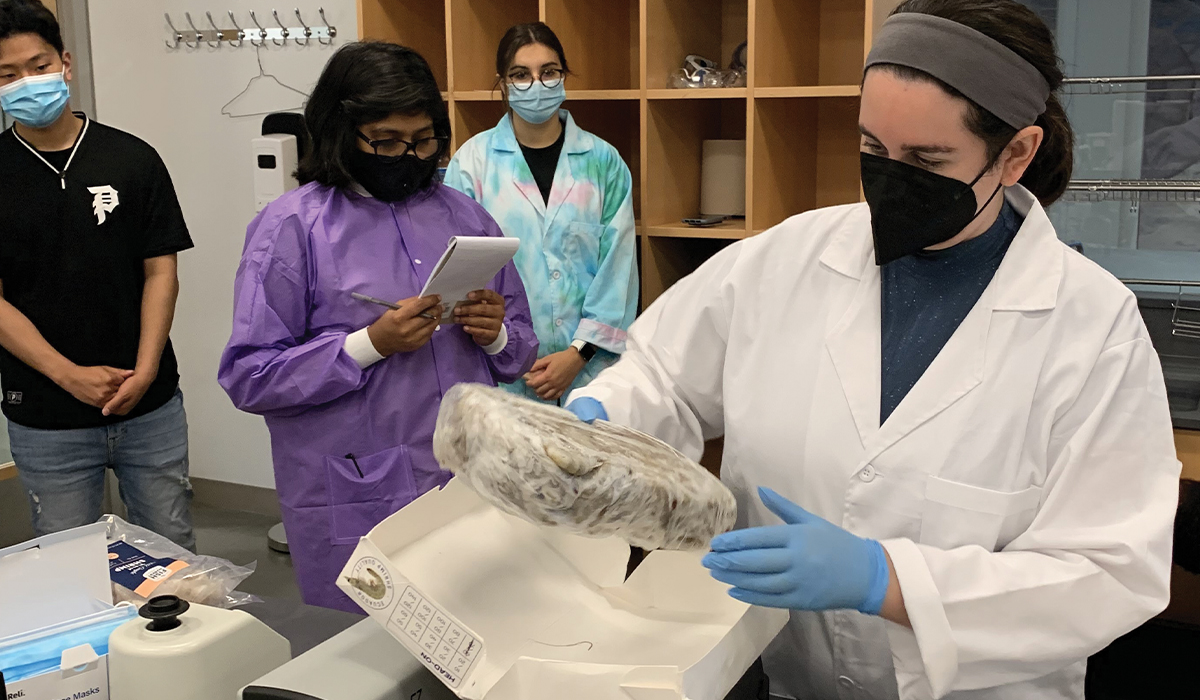

Four students — McKenna Rivers (MS ’23), Alexia Campbell ’23 and community college students Chris Haneul Lee and Pragati Kapoor — bought bags of frozen shrimp at grocery stores in Orange County and did lab analysis to determine net weights, ice glaze levels and DNA-based species identifications.

“It’s pretty laborious because you have to remove the ice layer from the shrimp, and you have to weigh it before and after,” Hellberg says. “So they were pretty tired of working with shrimp.”

Although shrimp is the most-consumed seafood in the United States, there’s little research into the extent of short-weighting and mislabeling, according to the study.

Some companies may mislabel imported seafood to avoid anti-dumping taxes or food safety requirements, Hellberg says. Consumers should be concerned about short-weighting and mislabeling of seafood because of health concerns, overpaying and sustainability, she says.

Some companies may mislabel imported seafood to avoid anti-dumping taxes or food safety requirements, Hellberg says. Consumers should be concerned about short-weighting and mislabeling of seafood because of health concerns, overpaying and sustainability, she says.

“It’s happened with things like pufferfish being mislabeled as monkfish, where pufferfish have a toxin — people ate that and got sick from that,” she says. “Now obviously, that’s different from the shrimp scenario. But any time you have mislabeling going on it misleads consumers and regulatory authorities in terms of the possible health risks or health hazards.”

A health risk in shrimp is antibiotic residues from farming, Hellberg says. Additionally, people and companies may unknowingly overpay for shrimp because the processor has added extra ice, increasing weight.

“Another important reason is for consumers to be able to know exactly what they’re purchasing,” she says. “Some types of shrimp are more sustainably harvested compared to others. And so consumers interested in purchasing sustainable options are being misled if the seafood is mislabeled.”

Shrimp species names can be confusing, and companies are supposed to stay within labeling guidelines. One of the most common types, whiteleg shrimp, is often wrongly labeled as another species, white shrimp, Hellberg says.

“They sound very similar but they’re actually quite different,” she says. “White shrimp is one of the main species in wild-caught fisheries in the U.S. Whiteleg shrimp is commonly farmed and imported … it’s misleading to consumers.”

Hellberg recommends training and outreach about proper labeling, and more research worldwide into overglazing, short-weighting and mislabeling the country’s most popular seafood. She shared her results with NOAA Fisheries, the USDA and the FDA, and says the FDA is looking into increasing surveillance efforts for frozen shrimp.

The shrimp study is just Hellberg’s latest dive into seafood. She’s finishing a study on canned tuna and published a study on short-weighting of frozen fish a few years ago. Last year, she published a paper about the prevalence of mislabeling ready-to-eat raw seafood — poke, sushi and ceviche. Her students went to restaurants around Orange County.

“Some ceviche products we bought that were supposed to be fish actually had shrimp. So that would be a concern with allergies,” Hellberg says.

She says she doesn’t have another shrimp study planned, but other types of shellfish may be next on the research menu.