In 2019, Abigail Stephens ’26 was a first-year student at Canyon High School in Anaheim when her poem, “My Enemy, My Friend”, won first place in Chapman University’s Holocaust Art & Writing Contest. This year, Stephens — who is now a history major at Chapman — will serve as a judge for the contest’s 25th anniversary.

In 2019, Abigail Stephens ’26 was a first-year student at Canyon High School in Anaheim when her poem, “My Enemy, My Friend”, won first place in Chapman University’s Holocaust Art & Writing Contest. This year, Stephens — who is now a history major at Chapman — will serve as a judge for the contest’s 25th anniversary.

For Stephens, the highlight of the whole experience is the opportunity to interact with Holocaust survivors and educators. Those conversations have helped her to see survivors not just as statistics or as their stories of trauma, but as people who have built fully-rounded lives post-tragedy.

“I could really sit down and talk to them about what they’re doing now,” she said. “Talk about what they like to do. I talked with one of the survivors about how we both swam every day, and I was talking to another woman … about how she hates salad …That’s one of the first things I learned. These people are humans, and not just a story.”

Adding Faces to the Facts

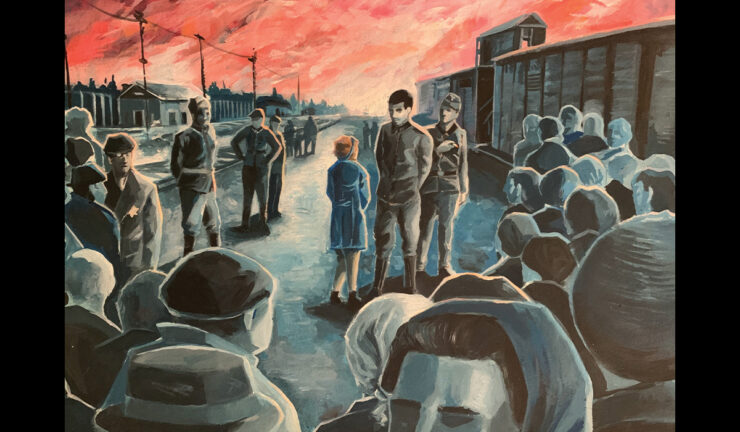

The facts about the Holocaust are easy to find: Between 1941 and 1945, the Nazi government systematically murdered 6 million Jewish people from across German-occupied Europe.

But for 21st century students, even the most basic facts can be opaque. Currently, only 25 U.S. states and nine countries worldwide require Holocaust education, and as many as 6 out of 10 Americans under 30 cannot accurately identify how many Jews were killed in the Holocaust.

At the same time, incidents of antisemitism in the U.S. have risen 428% over the last ten years, according to the Anti-Defamation League’s Center for Antisemitism Research (CAR). Jewish people are less than 2% of the U.S. population, but 60% of the faith-oriented hate crimes target Jewish communities. The CAR research suggests a direct relationship between the lack of Holocaust education and the increase in prejudicial, antisemitic beliefs.

For Holocaust Art & Writing Contest organizers Marilyn Harran and Jessica MyLymuk, these current realities are just as important as the history they study. They also know that the facts alone are not enough to convey the lived experiences of those who endured this history, nor can they inspire the personal connections that are essential to answering the call, “never again.”

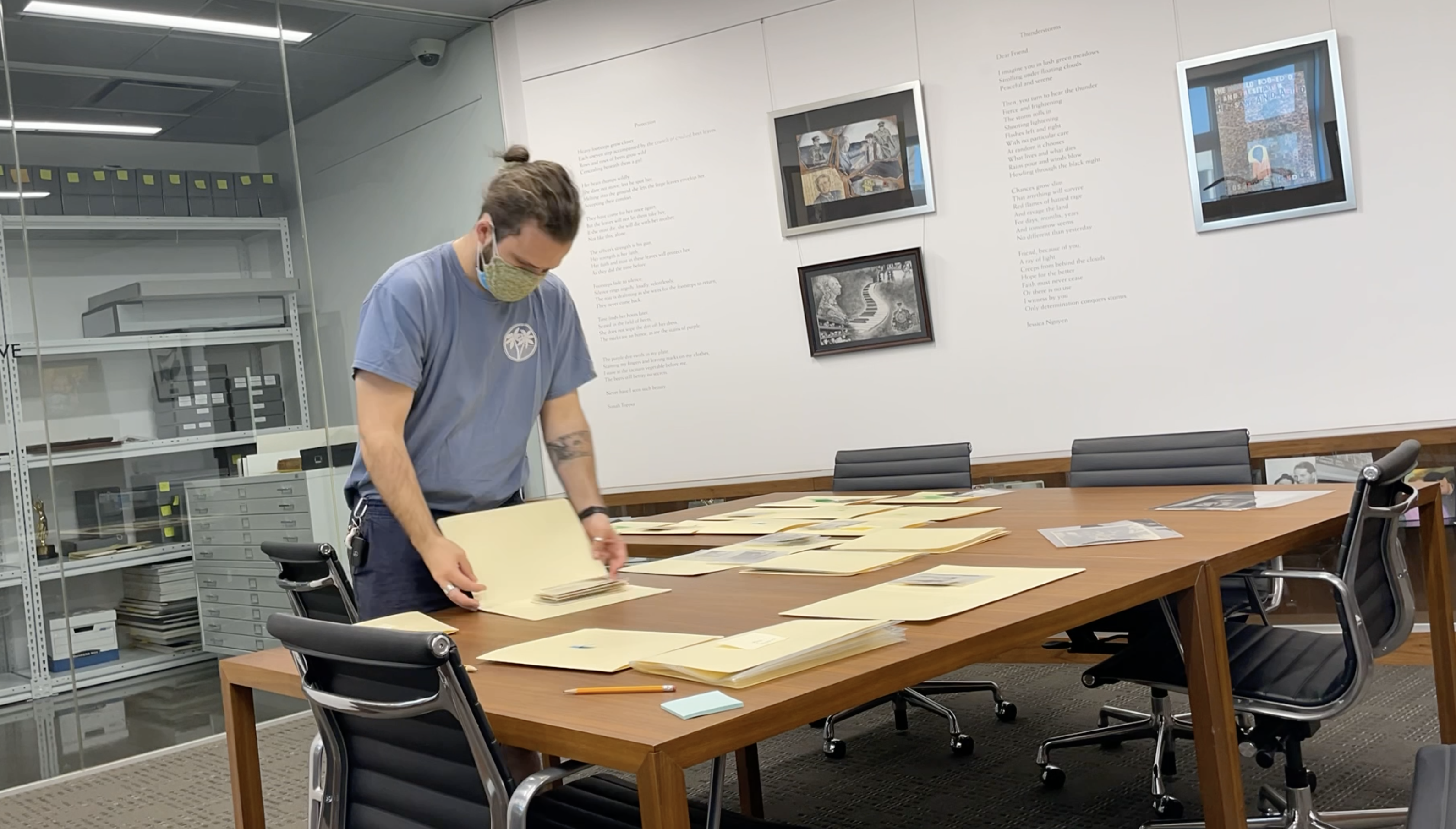

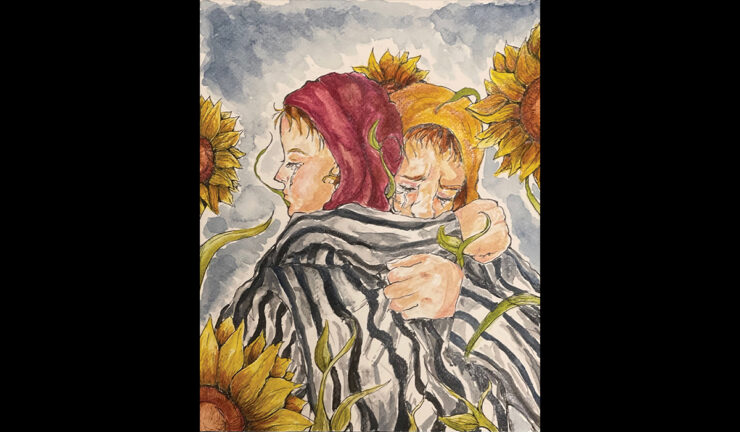

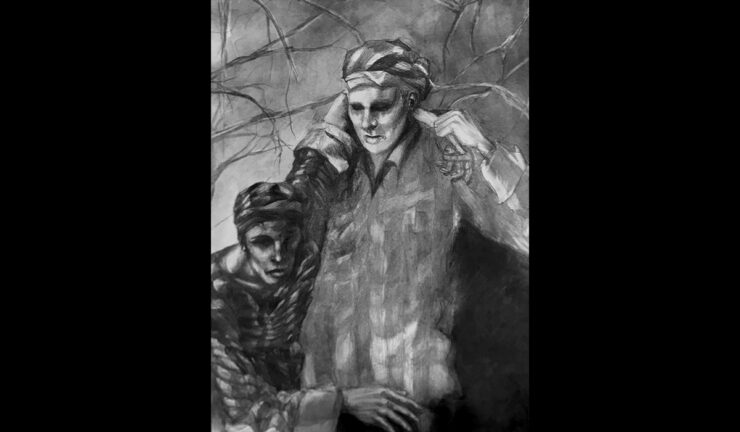

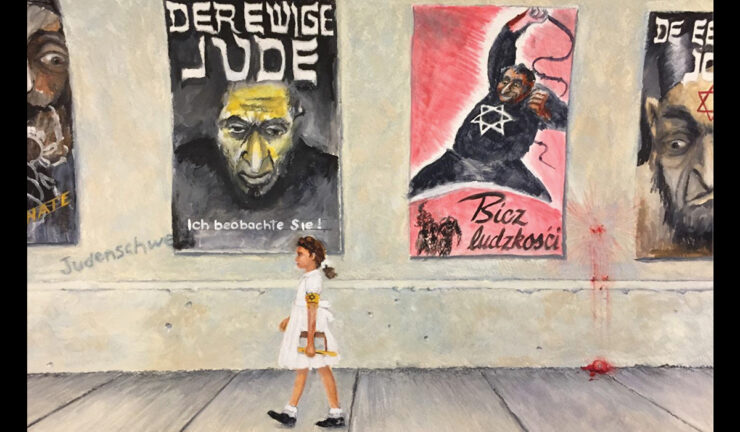

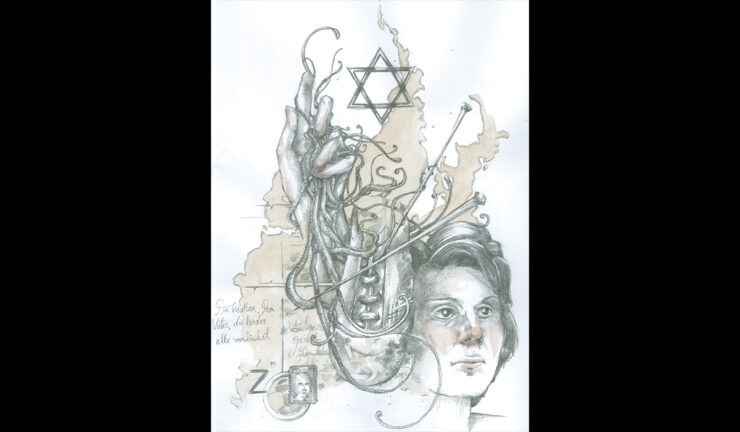

Co-sponsored by The 1939 Society and supported by the Samueli Foundation and Dana and Yossie Hollander, the contest has welcomed some 150,000 middle school and high school participants throughout Orange County, across the country and around the world. Students are asked to watch testimonies recorded by Holocaust survivors or rescuers and respond through their own creative work – essays, poems, visual artwork and film. Representatives from each school, along with their teachers, attend the awards ceremony and reception where students and survivors meet. Winners also participate in a four-day summer study trip to visit the Holocaust Museum LA, the Japanese American National Museum and other sites in Los Angeles, as well as to meet with members of The 1939 Society, a community of Holocaust survivors, descendants and friends.

“We have always sought in diverse ways to build a connection between students and the survivor,” says Harran, who is the founding director of Chapman’s Rodgers Center for Holocaust History and holds the Stern Chair in Holocaust Education in Wilkinson College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences.

The commitment to ask students to view a full-length survivor testimony in order to get a sense of what their life was like before and after dates back to the contest’s earliest days.

“There is some criticism about Holocaust education and how it does or does not address concerns about antisemitism,” says MyLymuk, associate director of the Rodgers Center. “One of the criticisms is that it paints survivors as victims. That we are so kind of entrenched in their tragedy that we don’t see them as whole people. If you don’t know what their lives were like, you don’t know what they lost. You also just don’t see them as anything beyond what their trauma is.”

The opportunity to engage with survivors as individuals and not just statistics is the first step in building empathy and showing students that Jewish lives are not so different.

From Generation to Generation

For Mindi Seigler (MAT ’09, Ph.D. ’16), a 9th grade English teacher and Chapman alumna, the contest has become a core facet of her curriculum not just in her own classes, but through every grade level at Hawthorne Math & Science Academy in Hawthorne, Calif.

“Some of the students go really deep and they get really personal,” says Seigler, discussing her students’ experiences. “This becomes for them not just a contest to win … they really want to do their best because they take pride in knowing that if the survivor was alive in front of them, they would want to be able to reflect back to the survivor, ‘Your story meant something to me, and now that I know your story, I can’t unknow it.’”

The need to create empathy across time and generations lies at the heart of the contest’s purpose.

“There are so many different people who are touched by this contest,” says Stephens. “It builds empathy in students. Because sometimes I think high school students are [very] unempathetic, like little kids. And we need to fix that.”

While the experience can be impactful for students, it is just as meaningful to survivors.

“There have been some dry spells, I think, where sometimes it might have felt as though people weren’t listening anymore,” says MyLymuk. “And then you come to an event where you’ve got a thousand people in a room celebrating the fact that they have listened to these stories, and celebrating and honoring the survivors as well. We could see their spirits lift. It meant the world to them to be able to come in and be with the students, to hear what they had to say and know that they’d been heard as well.”

This generation of students will be the last to meet a Holocaust Survivor in person — a fact pointed out by William Elperin, president of The 1939 Society, when he first proposed the contest to Harran twenty-five years ago.

“The contest spreads awareness of survivors’ stories, teaches us the lessons of the Holocaust and creates links between survivors and future generations,” Elperin said. “We now must all work harder to teach and learn the lessons of the Holocaust, so it never happens again.”