Sanika Pandit ’21 still remembers her excitement when the box arrived on her doorstep. Inside was a 3D printer – a tool that would become her textbook for the Fowler School of Engineering class Topics in Computer Science: 3D Printing and Design.

Then she opened the box and things got a bit more complicated.

“It was like my worst IKEA nightmare,” Pandit said with a laugh. “Just lots of parts and pictures.”

The moment of assembly also introduced Pandit to the Fowler culture of perseverance, stretching beyond what’s comfortable and working with colleagues to create something unique and productive.

“I didn’t know the difference between a wrench and a screwdriver when I started building that 3D printer,” said Pandit, who took the course during the previous academic year. “But that’s when the class really came together.”

Students worked collaboratively, solving assembly problems and teaching each other workarounds. They developed a curiosity about and respect for the printer components while gaining a deeper understanding that allowed them to troubleshoot operational issues.

“The concept of collaborating and figuring it out is something that Professor [Jonathan] Humphreys really instills in us,” Pandit said of the class instructor. “I see that in a lot of my other Fowler courses as well.”

Class gets universal access to technology

Fowler Engineering Dean Andrew Lyon says the class reflects the school’s emphasis on democratization of learning. Instead of buying a few 3D printers and putting them in a lab where students would have to wait for a chance to use them, why not provide a printer to each student, so the chance to test and learn, experiment and grow is always available?

“Technology- or equipment-based learning is always plagued with bottlenecks,” Lyon said. “We decided we should take advantage of the fact that a bunch of companies have figured out how to make low-cost 3D printers that still deliver great learning outcomes and a hands-on laboratory experience.”

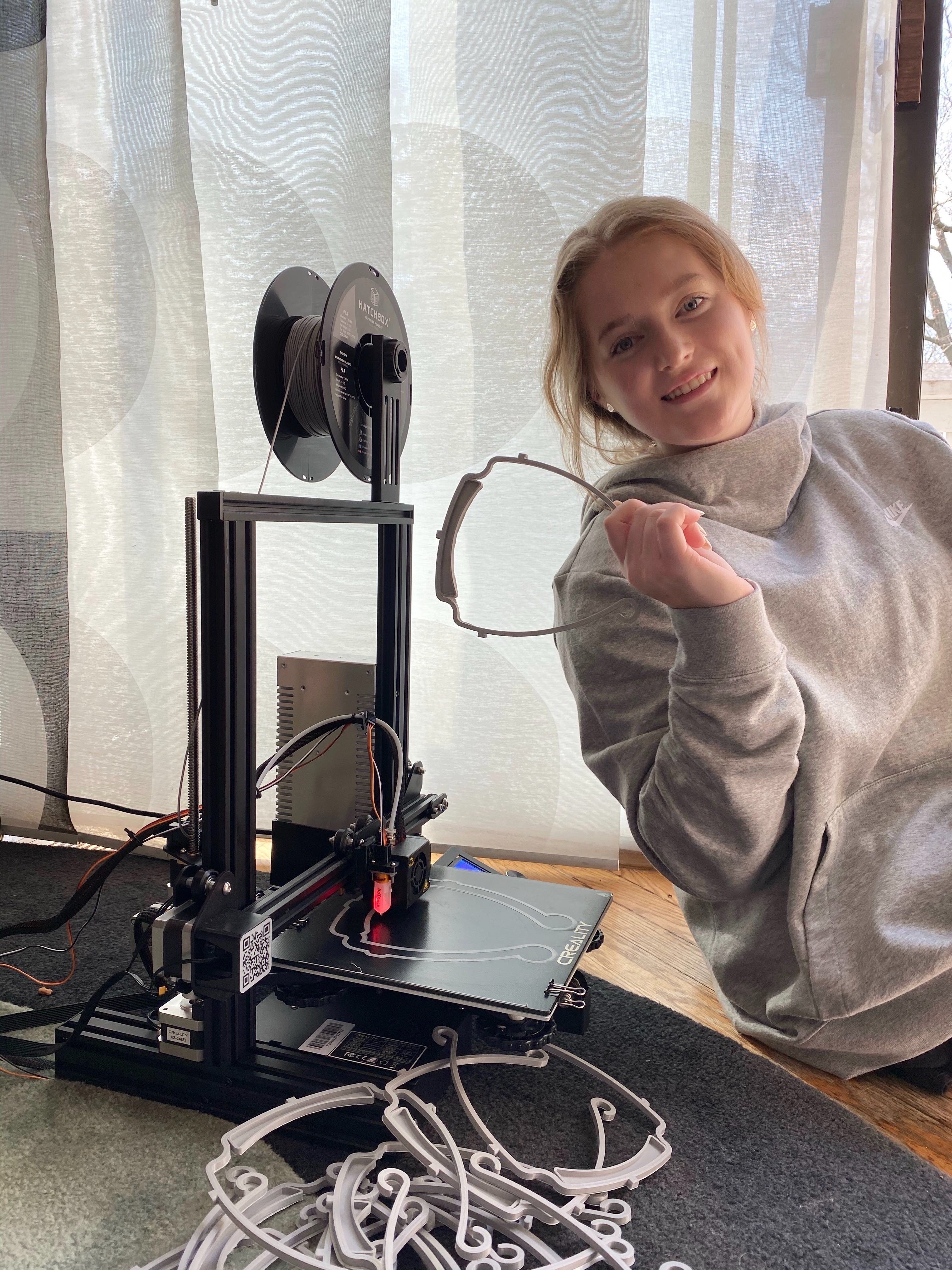

It’s been well-documented that students in the 3D printing class adapted quickly when the coronavirus pandemic forced a university-wide transition to remote learning. With printers already in their homes, the students shifted from other class projects to producing face shields for frontline healthcare workers. In a matter of weeks, the 20 students and Fowler faculty members delivered almost 5,000 shields to protect critical workers.

But long before the students responded to the COVID-19 crisis, the class members had a heart for advancing the greater good. Given a chance to choose a printing project early in last fall’s class, students opted to design and create Halloween costumes for youngsters in Higher Ground, a nonprofit dedicated to mentoring youth in underserved communities.

In the spring version of the class, students were working up to a project in which they would create prosthetic hands for amputees. Meanwhile, two veterans of the class, Oliver Mathias ’21 and Greg Tyler ’21 (M.S. ’22), continue to pursue better magnetic resonance imaging by transforming a flat-screen MRI into a 3D model of a human brain.

Grand Challenges Initiative sparks a focus on the greater good

It’s clear that the class has an ethos of altruism, which seems to spring from the Grand Challenges Initiative, a two-year project that involves all incoming first-year students in Schmid College of Science and Technology and Fowler Engineering. In the initiative, small teams work with mentors to take on some of society’s most pressing problems. Creative, community-focused thinking thrives.

That approach has become so much a part of the 3D printing course that it earned an unofficial name: “3D Printing for Good.”

“Mostly I stand around with mouth agape, watching these students,” says Humphreys, instructor for the 3D printing class. “I think it comes back to the democratization of the process. Each of them feels empowered by having a printer, and they feel like they can make a difference in someone’s life, whether it’s with a Halloween costume, the prosthetics or with the PPE’s. I’ve never seen anything like this.”

With tools of learning so close, “everyone can engage”

In the spirit of the 3D printing course, this fall Fowler Engineering is introducing a new course for first-year students – Engineering 101, designed to develop core competency in principles of design thinking as well as project management, electronics and embedded systems.

“It’s a course that typically would run in a laboratory on site,” Dean Lyon said. “But now we know what tools we can have the students maintain in their own homes or residence hall rooms so they can use them safely.”

For instance, by providing each student with a solderless breadboard – a standard electronics tool for creating prototypes of circuits – class members will have an expanded chance to create and test their circuits before using software to lay out a design for a printed circuit board.

“The cost of doing something meaningful and high-level has dropped,” Lyon said. “It means that everyone can engage – almost anyone can have a 3D printer, almost anyone can have an Arduino microcontroller [programmable circuit board and software used to write and upload computer code].”

Using such an approach, students “without any training in robotics can figure out how to build a robot in their garage,” Lyon added. “We had students in our Grand Challenges Initiative build a perfectly functional Fitbit heart monitor from scratch.”

“I came out of the class feeling like a full-fledged engineer.”

For Pandit, the 3D printing class was transformative. She came to it as a biology major who works in Lyon’s nanotechnology research lab but who said she “felt like an imposter” among engineering students.

“I came out of the class feeling like a full-fledged engineer,” she said. “It gave me the confidence to take the leap as a double major in computer science.”

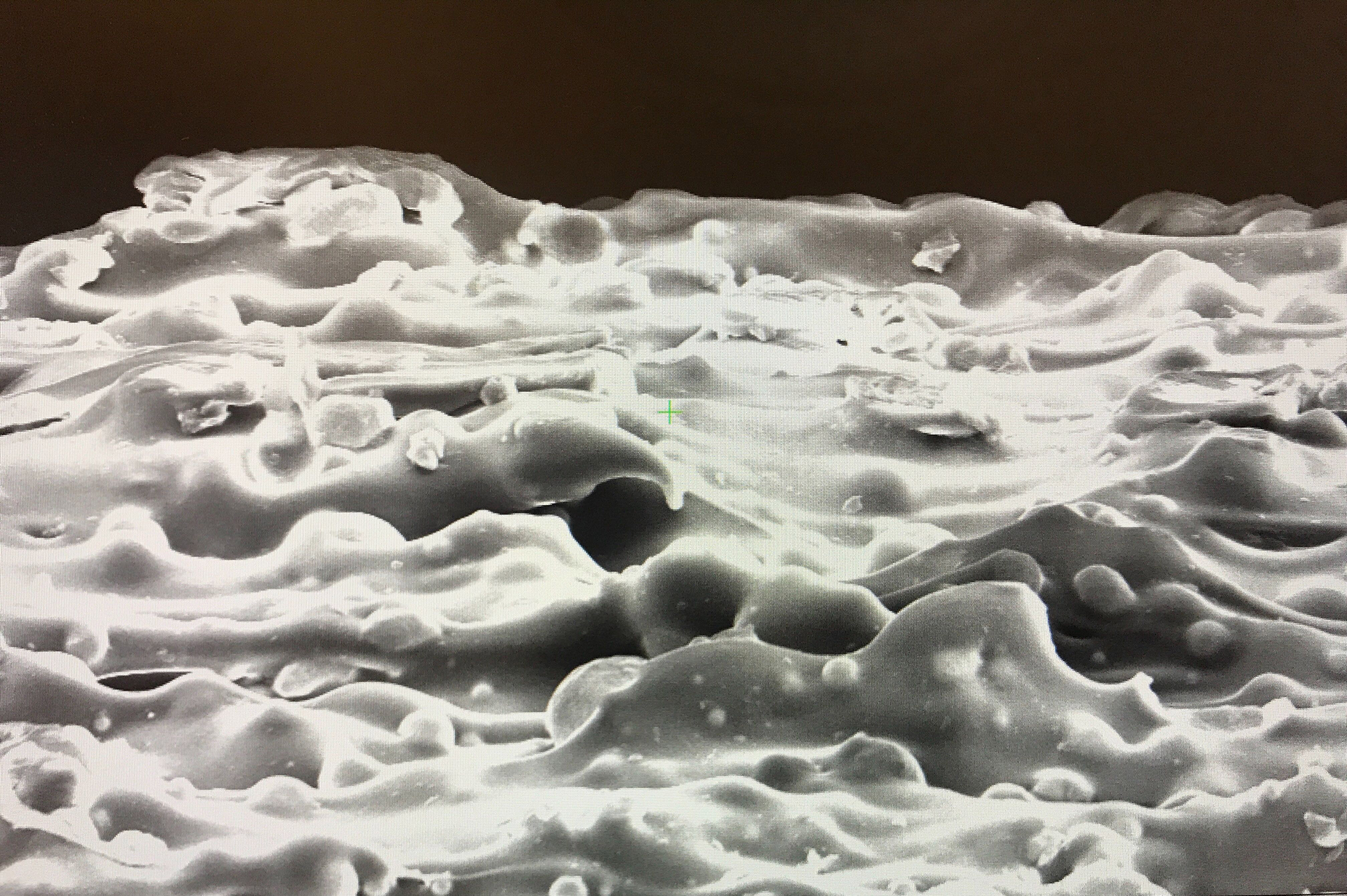

During the spring semester, she served as a student instructor for the 3D printing class, which also attracted majors in history and art. Pandit developed an interest in materials imaging, so she asked to use the school’s electron microscope to capture images of 3D printing filaments that include embedded fibers of carbon, metal and fiberglass.

“Most universities would say, ‘No, that’s for grad students.’ Instead, the message to her was go grab as many materials as you can,” Humphreys said. “Now we have these phenomenal images that help us better understand the materials we’re using.”

Pandit says that everything about her Fowler Engineering experience has been welcoming and empowering.

“We’re given the tools to explore – to find out what’s out there, what we like and what we can do,” she said. “I wouldn’t trade the experience for the world.”