Sonia Kelly and Judy Richonne (M.A. ’18) step wordlessly between rows of crosses, searching for the grave of their Silent Hero. Richonne, a teacher of high school history as well as a student in Chapman University’s War and Society master’s program, has come to Normandy to honor one of the many who gave all on D-Day more than seven decades ago.

Richonne has mentored Kelly through months of research so the high school junior can tell the story of Private First Class Tony Burnett Jr., a paratrooper from Pasadena whose plane was shot down before he ever got a chance to make his D-Day jump. Later, Kelly will deliver a graveside eulogy for Burnett in the company of fellow student researchers and their teachers. But first Kelly and Richonne have a hands-on plan for helping Burnett stand out among the 9,387 comrades in arms buried in the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial along the now-peaceful French coastline.

They carry a bucket of sand collected from Omaha Beach, and when they reach the grave of the soldier they now affectionately refer to as “our guy,” they kneel, and Kelly begins rubbing the sand over the letters engraved in the cross. For a few moments before they wash the stone marker clean again, Private Burnett’s name is visible all across the sands of history.

This simple action gets to the heart of their journey.

“It’s no longer a research project – it’s Tony – and that is the goal of the project,” says Richonne, who teaches at University High School in Irvine and is a past winner of the National History Day Teacher of the Year award. “We get a chance to make sure that this person is not remembered as a casualty, to give him a voice and ensure that he’s not a silent part of history. That makes this a powerful experience.”

Richonne and Kelly began their experience on Memorial Day, after they were selected as one of only 15 teacher-student teams nationally to take part in the Normandy: Sacrifice for Freedom program of the Albert H. Small Student & Teacher Institute.

They chose to tell the story of Private Burnett because he’s a Southern Californian, making it easier for them to meet and interview family members. They also comb through records during a trip to the National Archives in Maryland and other research sites. Then there’s the journey to Normandy for more research and to establish historical context for the D-Day invasion.

The project connects to Richonne’s Chapman War and Society studies in deep and meaningful ways, she says.

“My goal is to help my students become engaged, proactive citizens instead of passive members of society,” she says. “We’re thinking about ways of shifting from a society in a state of war to one in a state of peace, and this is the part of the War and Society program that fascinates me. How do we say as a nation that our diplomatic choice now is to go to war? What has to happen to get to that place?”

On the ground in Normandy, Richonne and Kelly tour homes that were occupied by the Germans during World War II. They walk the Pegasus Bridge, site of a critical Allied foothold in the earliest moments of the D-Day invasion. They wade into the surf and imagine struggling toward the beach while wearing packs that double their weight. They step into craters so broad and deep that it’s hard to grasp the destructive power that created them.

“No wonder so many soldiers couldn’t fathom going back to reality, because their reality had been redefined into something horrific,” Richonne says.

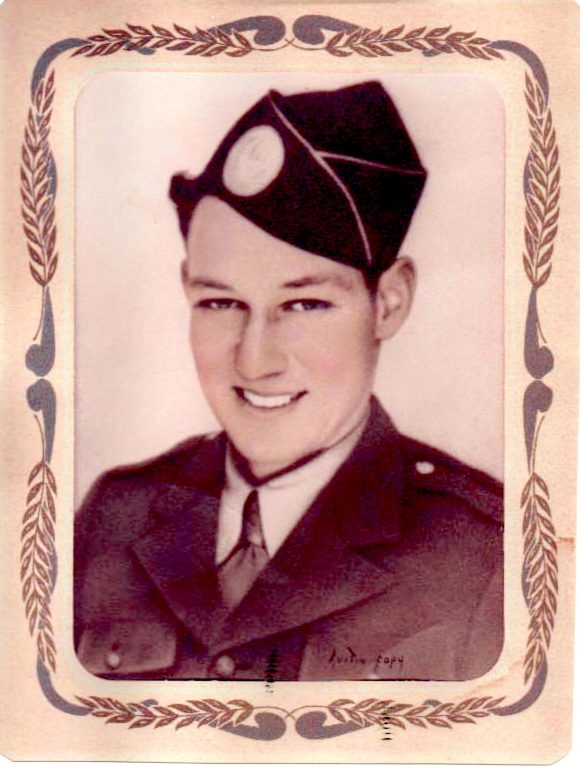

Throughout the Normandy experience, she and Kelly do their best to place themselves and their fellow researchers in the boots of Private Burnett – as he boards a C-47 at Welford Airfield on the “day of days,” chute on his back and folded American flag in his pocket; as he and other members of the 3rd Battalion, 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division take off in the last of five waves to cross the English Channel; as his plane gets hit by intense antiaircraft fire and crashes near an apple orchard; as he makes the ultimate sacrifice for the cause of liberating Europe from Nazi tyranny.

“From his easy smile to his kind personality, Private Burnett has not been forgotten by those he affected,” Kelly says in her eulogy at his graveside. “Mrs. Richonne and I are two of those people, and from now on we will celebrate his extraordinary 20 years and remember his selflessness for his country and the world we share.”

For Richonne, the bond with Private First Class Tony Burnett Jr. has become “an adopted son kind of thing,” she says. “He’s younger than my own children, a bit older than my high school kids. I could imagine sending my only son into the unknown, where the chances of him coming home are pretty slim.”

These days, she is back in her classrooms– at University High and at Chapman. But in her mind, she can easily return to the rows of crosses, where she sees the names of soldiers whose stories have yet to be told.

“You realize how many are still unknown, and that’s the idea of the Silent Hero program,” she says. “We’re trying to make them a little less silent.”

Display image at top/High school junior Sonia Kelly and her history teacher, Judy Richonne (M.A. ’18), partnered on a research project that took them to Normandy, France, to tell the story of a D-Day Silent Hero, paratrooper Tony Burnett. Here they put the finishing touches on a presentation to be delivered to the Normandy Institute.

This story appeared in the fall 2017 issue of Chapman Magazine.

Add comment