Chapman University’s section of the Berlin Wall is such a part of the campus landscape, nestled in a quiet reflecting pool outside Roosevelt Hall, that even those with connections to the Cold War symbol are sometimes surprised by its presence.

“I never even realized it was here. Probably because I was in a hurry to get to class and back,” says Agnes Weltmann, a student from Germany who had family on both sides of the wall.

For Weltmann’s generation, that’s all history now. The Berlin Wall has been down almost as long as it stood. Twenty-five years ago this month it fell, a world-changing collapse helped along by peaceful demonstrations that rose up from the very people it was built to contain.

Today sections of the wall that divided East and West Berlin for 28 years are displayed around the world as reminders and memorials to that tense chapter of Cold War history. One portion stands near the center of campus, surrounded by a reflecting pool, lawn and benches that make up the Liberty Plaza installation created by artist and professor emeritus Richard Turner.

The wall’s footprint on history – and even the planet, if you consider an astronaut’s recent photo of Berlin – is still being studied. But to reflect on at least a bit of the human history attached to the graffiti-scarred hunk of concrete, we turned to people from the Chapman community with four different perspectives on the wall that came down Nov. 9, 1989.

-

- Chapman University Trustee David C. Henley was a foreign correspondent in Germany at the time the wall went up, and he helped two children escape East Berlin.

-

- Karen Gallagher, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Department of World Languages and Cultures, spent part of her childhood in the shadow of the wall while living in West Berlin.

-

- Marilyn Harran, Ph.D., professor and the director of the Rodgers Center for Holocaust Education, in November 1989 was studying in the city of Leipzig and witnessed the Monday demonstrations that flowered into the people’s movement that helped bring down the wall.

-

- Weltmann and fellow international student Luiz Zuch are young Germans who know the wall mostly as a historic artifact.

An Escape Remembered

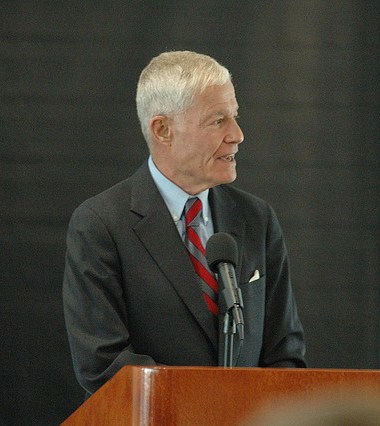

While working as a foreign correspondent, Trustee David C. Henley helped two young children reunite with family in West Berlin. Henley recounts the experience and others from his 60-year career in his memoir

From Moscow to Beirut: The Adventures of a Foreign Correspondent

.

He doesn’t remember their names. Never knew what became of them. But David Henley, a Chapman University trustee, does remember one thing about the night he piled blankets and a spare tire on top of a little girl in the backseat of a Volkswagen and smuggled her and later her brother out of East Berlin.

When he got to Checkpoint Charlie at the border, “I was shaking like a leaf,” says Henley, who was a foreign correspondent in Germany days after the border was closed. Those early days when the democratic West Germany was sealed off from communist East Germany were frightening, he recalls. Armed guards were everywhere. There was no way to communicate via phone or mail. The “death strip” near the wall was covered with raked gravel and sand, making it easy to spot footprints, and was booby-trapped to prevent escape. As a journalist he had freer passage between the border and was talked into smuggling the children by a few American students and others helping to reunite families. He says he was just plain lucky that night when he made it to the border because the guards only looked at his press card and waved him on. He repeated the same harrowing journey the next night with the little boy.

“It was a very foolhardy venture, but I wanted to help get those children out,” he says. The children were reunited with their parents, who had fled to West Germany earlier. That’s all he knows about them. “But I will never forget it,” he says.

A Child’s Memory

Assistant Professor Karen Gallagher.

As the daughter of a German mother and an American father who worked for Pan American World Airways, Gallagher grew up mostly in Europe, including five years in West Berlin. Among her childhood memories is a field trip to see the wall – particularly unforgettable from a child’s point of view because one of the students was hit by a brick that tumbled off a crumbling building on the western side.

An uneasy trip to visit cousins in the east also stands out in her memory.

“When we crossed the border, I had a beanbag doll and I was concerned that the guards would cut open my doll (to search), but they didn’t,” she recalls. “And our relatives were paranoid. They didn’t want neighbors to know they had guests from the west, so they hid our car in the garage.”

Her proximity to the east fostered a deep feeling of privilege, Gallagher says. So much so that when she visited Leipzig last summer as a

Fulbright Summer Academy

fellow, one of the most striking takeaways from her home-stay visit were conversations she had with the older woman who hosted her. While the woman had been forbidden from travel and other liberties, she shared that life behind the wall wasn’t always an abysmal experience. The retiree was grateful that she had been able to successfully build a career and rear children as a single mother in the communist society, something that western counterparts of her generation tell her was harder for them to achieve.

The trip still resonates with Gallagher: “This wall in our heads is slowly disappearing.”

The Monday Night in Early November

Leipzig is also at the center of Harran’s experience with the wall. She was there studying under an international fellowship when the

Monday Demonstrations

that helped fuel the wall’s demise grew and poured into the streets outside her apartment window. Harran recalls:

From her sixth-floor apartment in this building, Professor Marilyn Harran watched the street fill with peaceful demonstrators.

“From my apartment by the Nikolai square, I literally had a view no other American—no other Westerner—did. I had no telephone and no way to contact the American Embassy in Berlin, so at times I felt isolated and apprehensive. Certainly I did the Monday evening that a Stasi officer stood outside my apartment building checking passports and papers of everyone in the building and forbidding us to have any visitors. The authorities didn’t want anyone else to have the view I did. I can still hear the thousands of people who shouted over and over again, ‘Wir sind das Volk, ‘We are the people.’ I’ll never forget the courage of the tens of thousands—ultimately hundreds of thousands—who gathered peacefully to demonstrate for change, even when loudspeakers positioned on the streets repeated the words, “Go home; do not demonstrate” and the threat of armed intervention by the Soviets hung in the air.

“If I had to choose just one memory from the many I have of that time, it would be the Monday night in early November, just about this time 25 years ago, when I looked out my window at the hundreds of thousands of people gathered in the square and far beyond. To my utter amazement—I still can’t quite believe it—I heard people begin spontaneously singing, in English, We Shall Overcome. Even though it’s been 25 years I can still hear those voices in my mind. It was truly one of the greatest experiences of my life.”

‘Back to a Good Life’

Chapman students Agnes Weltmann, 20, and Luiz Zuch, 24, know all about the wall’s history and recount their visits to the Berlin Wall Memorial as insightful experiences. The memorial’s informational walking trail that follows the wall’s path especially fascinated Zuch, who enjoyed jumping “from East to West” along the trail and marveling at the divide that once stood there.

Agnes Weltmann and Luiz Zuch, international students from Germany studying at Chapman University this semester, say they are grateful to come of age in a unified Germany.

“It’s very good that we still have the memorial, and part of the wall within the city is still part of it, because they thought of tearing it down,” says Zuch, who is studying international business in the

Argyros School of Business and Economics. “I definitely have to deal with my history and what my ancestors have done and had to deal with. I want to have that knowledge. I want to know how they felt at the time.”

Weltmann, who’s studying athletic training in the College of Educational Studies, even has a family story associated with the wall. Her mother had a childhood book in her backpack seized by border guards when she traveled with her family to East Berlin to visit relatives. The picture book of an American Indian and Western cowboy overcoming stereotypes to forge a friendship was deemed “revolutionary.”

Weltmann and Zuch know well the wall’s sinister history – that more than a hundred people were fatally shot while trying to escape from the East and countless others suffered under Soviet dominance. And they acknowledge that rebuilding and compensation programs continue in the former East Germany. But both say it’s the story of the wall’s demise and the opportunities that came with Germany’s unification that resonates with them today.

“It’s a happy association,” Weltmann says. “I know that (the history) happened. But the first association that I have is that it came down and people found their way back to a good life.”

Did you know?

Chapman University’s piece of the Berlin Wall was obtained thanks to the efforts of President Jim Doti, Professor Marilyn Harran and generous donors. Read the history in this Los Angeles Times story.

Thank you all for sharing your reflections on a part of history we should never forget.