The football field was hot and muggy, thanks to August heat reflected by synthetic turf and magnified by a humid storm system hovering just beyond the Santa Ana Mountains. Textbook conditions for heat illness in a gear-intensive sport like football.

Within seconds,the player is cradled in a plastic tarp that can be a cooling tub when ice water is poured in.

That’s why at this time of year Pam Gibbons, Chapman University’s head athletic trainer, orders up a nice, cooling ice taco. An ice taco drill that is.

It’s a low-tech but effective method for cooling overheated athletes. A Panther football player was enlisted to fall into a state of mock heat exhaustion, prompting Gibbon’s crew of fellow certified athletic trainers to race in with a plastic tarp, roll the player onto it, hoist it aloft and pour simulated ice water into the taco shape that would cradle the athlete in a cooling, potentially life-saving bath.

The drill took just seconds, and the team applauded. “We just saved a life,” called out one of her student assistants.

Indeed, that blend of preparation, practice and expertise led by a certified athletic trainer is a formula that prevents serious and fatal heat stroke on football fields every fall. But just as the heat rises and high school athletes hit the fields this month for tough practices in heavy gear during the sport’s traditional “hell weeks,” researchers in the Chapman’s

Athletic Training Education Program say many California high schools are ill-prepared to deal with heat illness because they lack such emergency plans or staff.

“The high schools are not as aware as they should be,” says Michelle A. Cleary, associate professor and a leading researcher in heat related athletic injury.

More than 9,000 high school athletes are treated for exercise-related heat illness annually, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Of those, some 75 percent occurred in August during preseason practices. Just this week a

14-year-old Florida football player died from apparent heat stroke.

Biggest risk? Younger teens

Young athletes are particularly at risk because many don’t have the year-round fitness habits of collegiate and professional athletes, Cleary says.

“I always give the example of the kids who are sitting around all summer long playing video games indoors in air conditioning and then they show up for football practice totally unacclimated,” she says.

Freshmen especially pose special challenges, says Jason Bennett, D.A., ATC, associate professor and director of Chapman’s athletic training program. They may be new to the sport, overweight or intimidated by the competitive environment and hesitant to take extra water breaks, he says.

Increasingly, there’s the synthetic turf factor. While much of California is spared the kind of heat that players face in the southern states, the West’s drought has fostered a preference for synthetic playing surfaces. Bennett’s research has found temperatures on synthetic fields to be up to 20 degrees hotter than on natural turf. It’s not unusual for field crews to hose down artificial turf in a well-meaning attempt to cool them down.

“But that increases the humidity and makes conditions for the athletes even worse,” Bennett says.

Parents can call for change

Along with awareness and education, part of the solution is to urge schools to include certified athletic trainers in the athletic program staffing, Bennett says. Trainers can perform preventive work coaches don’t have time for, like conducting weigh-ins before and after practice to spot excessive water loss to dehydration, reviewing medical records or discreetly keeping an eye on the athlete with the new asthma medication.

Professor Michelle A. Cleary

Professor Jason Bennett

Bennett has researched why so many California high schools are reluctant to include certified athletic trainers, and he found that it mostly comes down to budget, but others cite legal concerns, he says. Some schools fear that by providing health and safety staff, they will bear even greater liability if something goes wrong.

Certified athletic trainers are trained for the worst-case scenarios, but the lion’s share of their work on campus is in preventing them, says Cleary, who helped write the heat illness prevention and treatment protocols for the National Athletic Trainers’ Association.

“Heat illness is 100 percent preventable, which is what makes it so frustrating when we see deaths of kids from heat stroke during football,” she says.

The best thing parents can do if their school doesn’t have a certified athletic trainer is lobby the school or district administration to earn the Safe Sports School Award, a blue-ribbon honor given to schools that take steps to prevent a variety of injuries, from heat stroke to concussion.

And until the day that award arrives, ask questions and keep nudging, Bennett says.

“Be ‘that’ parent,” he says. “It comes down to this – we need to take care of our kids.”

How can you keep your football player safe?

Got a child in football camp soon? Exercise-related heat illness has many levels, including mild muscle cramps, moderately serious heat exhaustion and at its most severe, heat stroke, a medical emergency that can lead to coma, kidney failure and death. Here are a few key prevention tips from Chapman’s Athletic Training Education Program faculty.

-

- Water should be available at all times and players allowed to access it when needed. Mandatory water breaks should be called every 15 minutes. It is never OK to deny water as a form of punishment.

-

- Make sure players are being slowly acclimated to heat and full gear outdoors — a 10- to 14-day process. Once helmets are in use, players should be allowed to take them off during breaks.

-

- After being acclimated, athletes sweat sooner and the body gets better at conserving sodium. Be extra vigilant about hydrating with water before play and non-caffeinated sports drinks once activity begins.

-

- Dump the caffeinated power drinks and sodas on practice and game days. Caffeine accelerates dehydration.

-

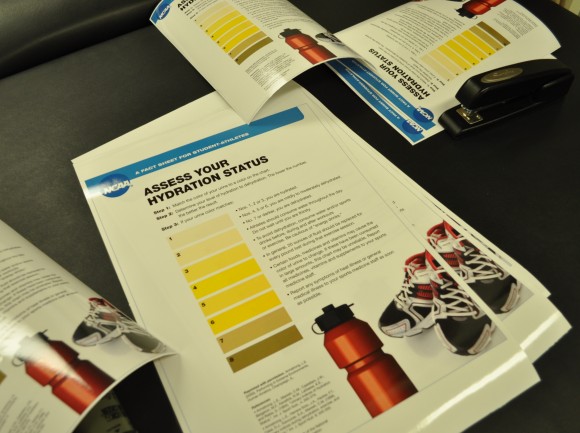

- Be alert for dark urine, a sign of dehydration.

-

- Learn more at the parents’ page of the Korey Stringer Institute.

Add comment