How do you share war correspondence from generations of U.S. service people with scholars around the world? You digitize the letters. That’s just one assignment in a graduate level digital humanities course taught by Jana Remy, Ph.D., Associate Director of Digital Scholarship. It’s a scholarly process that uses computers but can’t be done by technology alone. And as Cory Rasmussen (MFA ’17) discovered this fall as he worked in The Center for American War Letters, it can also be a journey of discovery.

Voices and the Past

I have a gift. It’s like a superpower. I can’t fly, bend things with my mind or control animals, but I feel, strongly. Ever since I was a little boy, I’ve been sensitive to emotion. It’s not a curse but a gift to feel so connected. Most times.

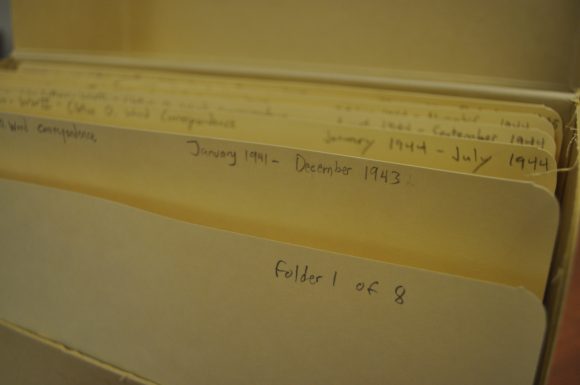

For class, we went to the basement of the Leatherby Libraries, which contains the silent voices of America’s past conflicts. Collections of letters are packed into many boxes. Through those letters

The Center for American War Letters

offers a lens into U.S. conflicts, from the Revolutionary War to the current conflicts in the Middle East. Our assignment was to explore three pieces of a collection. We’ll get to that, but let’s get back to my gift. Because I’m serious. When I walked into the room, a Korean War banner demanded my attention. There was a photo of a letter, and a snippet of its text stood out. I instantly thought of my grandfather who passed away this year. He fought in that war. He shared in the experiences of that letter. As I read some of the letters on the wall, the emotion hit.

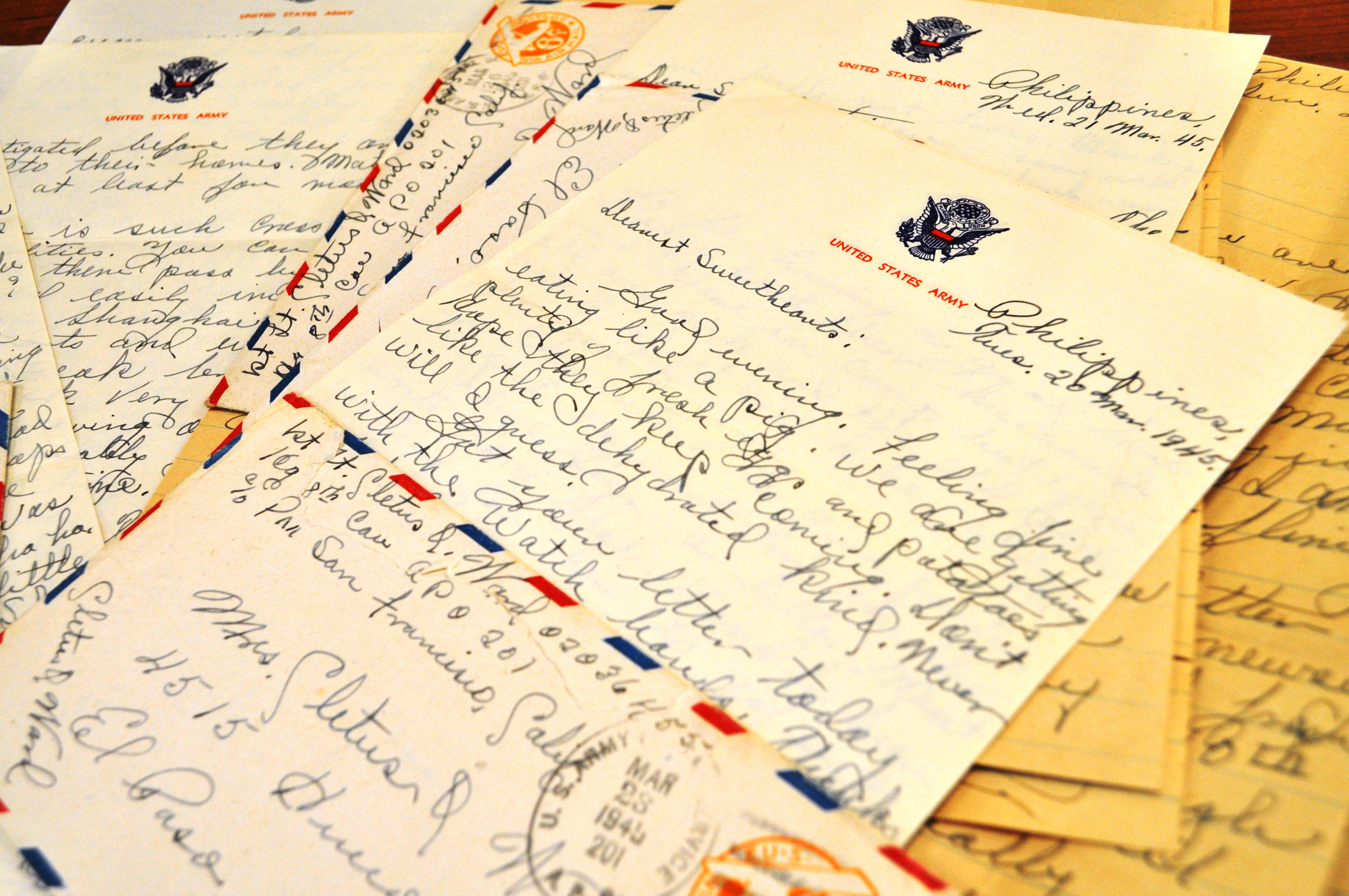

My eyes brimmed with tears as I realized that inside the next room there were boxes of voices, pieces of soldiers’ souls, documented in ink and paper. I felt a quiet respect wash over me, like I was at a funeral and the body was just in the other room. The course schedule stated I’d be digitally transcribing some letters. But I knew it was more than that. It was also an opportunity to pull apart the threads of time and follow a specific strand at a very important time within an American soldier’s life. This thought both worried me and excited me.

What is digital transcribing? It’s taking the envelopes and letters and transforming them into digital text so researchers from around the world can search key words and make connections among the letters. Think of doing a “search in document” in Microsoft Word. Here is an

example

of three letters that I digitally transcribed. Or, rather, attempted to, because it is such a careful process.

The letters I received were written by a WWII soldier, Cletus O. Ward, to his wife and child, and by a Vietnam-era Marine, Larry, to a woman in California. It felt eerie being privileged to a personal moment of their lives and made me question the ethics of my presence and intrusion, even though the letters had been donated. What right did I have to read something so personal? And yet, how fascinating and amazing it was to follow the thoughts of fellow Americans from different eras during a treacherous period of their lives.

When my classmate, Joanna, began to read out loud Cletus’ letter detailing the horrors of his camp being attacked, we realized that my calm letter, which focused on women and food, was written the day before hers. The emotion and imagination flooded my senses again. I felt anguish. Pain. Sadness. People died between my letter and hers. I was reading the ink that was pressed to the paper the day before his fellow band of brothers died. It’s like I felt the collective spirit of these soldiers. And as my imagination ran, I felt my soul being strung like a harp. I didn’t like that feeling. But I didn’t want to stop, either. I wanted to stare into the letter, blur the letters and let time flow backwards … let me warn his company of what’s to come.

But, alas, I can’t. It’s not my superpower.

The collection of war correspondence from Cletus O. Ward fills eight folders.

Buried somewhere among my grandfather’s things are the letters he wrote to my grandma while in Korea. One day, I think I’d like Chapman to have some of them. I’d love for his words to be immortalized and shared with the world. Though I placed Cletus’ and Larry’s words into digital text by my own fingertips awhile ago, the memory of them has followed me. Even now as I write. I’d like to immortalize my grandfather the same way. Let the world learn of his aspirations, his love, even memorialize the mundane aspects of war. Because they were

his

moments. And they were important.

Then again, is nothing sacred?

This essay was reprinted with permission from Rasmussen’s blog, Lightbulbs and Switches in Digital Humanities.

Add comment