The ballots have been counted and the presidential campaign that seemed as if it would never end is over. Yet the Chapman University Survey of American Fears makes it clear that fears highlighted by the divisive 2016 election existed before the first convention speech and aren’t likely to evaporate just because the votes have been cast.

“Fear of government corruption, the top fear for two years in a row, reflects declining levels of trust in government that we’ve seen over the past decades,” said Ann Gordon, Ph.D., an associate professor of political science and one of three principal investigators for the Chapman Survey of American Fears, first conducted in 2014. (Public trust in government reached a three-decade high shortly after the 9/11 terrorist attacks but has declined sharply in the 15 years since, according to data from the nonpartisan Pew Research Center.)

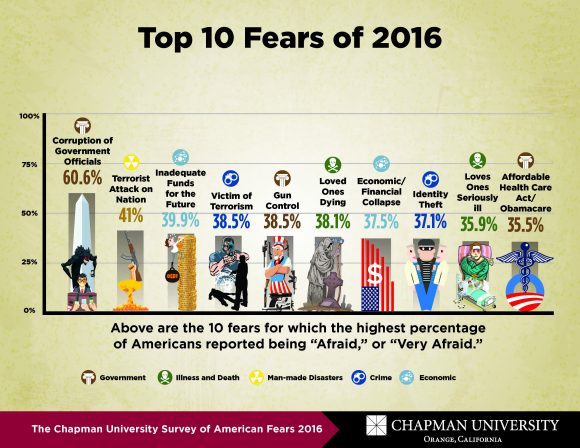

The 2016 Chapman Fear Survey, the first to be conducted in a presidential election year, was dominated by politically charged concerns. Fears of terrorist attacks, not having enough money for the future, being a victim of terror, government restrictions on firearms and ammunition, economic or financial collapse, identity theft and the Affordable Care Act known as Obamacare also ranked among the top 10 things Americans fear most.

The 2016 Chapman Fear Survey, the first to be conducted in a presidential election year, was dominated by politically charged concerns. Fears of terrorist attacks, not having enough money for the future, being a victim of terror, government restrictions on firearms and ammunition, economic or financial collapse, identity theft and the Affordable Care Act known as Obamacare also ranked among the top 10 things Americans fear most.

Nor does the climate of fear reflect the concerns of a single party.

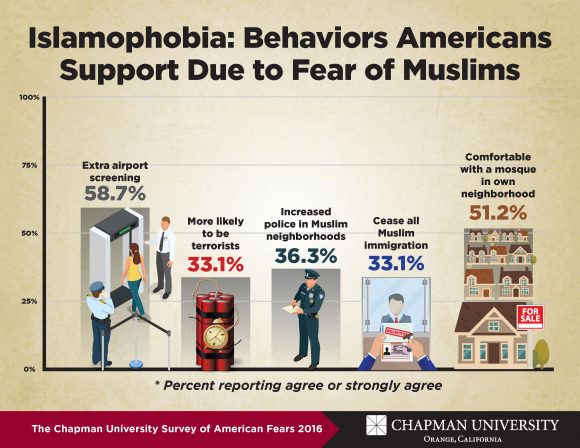

“Fears are driving both sides,” said Christopher Bader, Ph.D., a professor of sociology and a co-investigator with Gordon and Edward Day, Ph.D., associate professor of sociology. “For example, Democrats are more afraid of climate change than Republicans and less afraid of Muslims. But many of our fears do not show strong political differences.”

Politicians don’t create the fears that fuel their campaigns, Gordon and Bader said, but they may increase them.

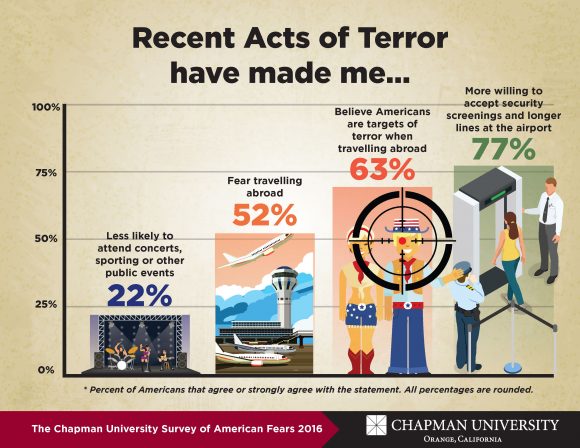

“The nature of the relationship is uncertain,” Bader said. “I would say that campaigns are adept at determining people’s fears and playing upon them. But political campaigns themselves by talking about fears are going to stoke them as well. Put another way, I think terrorism fears were not caused by the political campaigns, but the political rhetoric in this campaign has likely heightened those fears.”

“The nature of the relationship is uncertain,” Bader said. “I would say that campaigns are adept at determining people’s fears and playing upon them. But political campaigns themselves by talking about fears are going to stoke them as well. Put another way, I think terrorism fears were not caused by the political campaigns, but the political rhetoric in this campaign has likely heightened those fears.”

Fear appeals are not new to campaigns, Gordon said.

“The most famous example may be the “Daisy Girl” advertisement from 1964, in which President Johnson stoked fears that Goldwater would start a nuclear war,” she said, citing the television ad for Lyndon Johnson in his campaign against Barry Goldwater in which a small girl counted the petals of a daisy before a nuclear explosion.

“It’s important to note that the use of nuclear weapons had already been part of the campaign rhetoric, and the advertisement capitalized on those fears; it did not create them,” Gordon said.

“It’s important to note that the use of nuclear weapons had already been part of the campaign rhetoric, and the advertisement capitalized on those fears; it did not create them,” Gordon said.

Troublingly, a society predisposed to distrust government and believe in cover-ups might also be vulnerable to fabricated ones. Nearly a third of respondents in the survey believed the government is concealing information about “the North Dakota crash” – an incident the investigators made up, Bader said.

“We know that our government has engaged in conspiracies before – Watergate, Iran-Contra, etc. – but if it becomes the default position of Americans to distrust the government, this could have a huge effect on upcoming elections,” Bader said. The trend could be toward more extreme candidates, with programs that might serve the public good being victimized by fears that there is a hidden agenda behind them, he added.

The 2016 election is over, but the fears have not all been extinguished.

“Unfortunately, the fear of government officials, high distrust of government (as seen in our measures of conspiracies and others), do not suggest a more rational discussion post-election,” Bader said. “Some of the fire will naturally die down, but the long-term trends in distrust are troubling.”

Display photo at top of post: Student researchers contributing to the Chapman University Survey of American Fears include, back row from left, Annika Ford ’16, Andrew Calloway ’18, Kai Hamilton Gentry ’18, Sarah LeMay ’18, Brittney Souza ’18, Kunal Sharma ’18 and Natalie Gallardo ’18. The survey’s principal investigators are, seated from left, professors Christopher Bader, Ann Gordon and Edward Day.

Add comment