What begins in Earth orbit is now spurring grassroots response where environmental impact is most acute.

What begins in Earth orbit is now spurring grassroots response where environmental impact is most acute.

In a Chapman University cross-disciplinary course called “Observing Earth From Above: Using NASA Satellite Data for Real-Time Environmental Monitoring,” professors Gregory Goldsmith and Joshua Fisher help students translate remote-sensing information into community-based change.

“Greg and I had this common vision to do more than just another science project,” Fisher says. “We really wanted to expand this to capture climate disasters as they unfold in real time. There’s a need to keep up with the pace of both climate change and the media cycle.”

The scientists point out that their recent research study of heat-stressed trees in the tropics was three years in development before it was published as a cover story in the high-profile journal Nature.

“We need it to take three days to get research to the public, not three years,” Goldsmith says. Fundamental to the course is the professors’ work helping students learn to access and analyze data downloaded from a sophisticated remote-sensing instrument called ECOSTRESS, mounted on the International Space Station. But developing student skills in art, design and persuasive speaking is just as important.

“To do things like create effective climate policy requires an interdisciplinary team,” Fisher says. “We’re writing the recipe book on how to do that. These students are that interdisciplinary team.”

Sharing Science Findings to Drive Change

During a recent class session, students representing diverse majors – from engineering to philosophy – pitch their projects to Professor Susan Paterno, director of the journalism program at Chapman, and John Nielsen, a former science correspondent for National Public Radio. In previous class sessions, students also gleaned insights from Chapman art professor and information design expert Claudine Jaenichen as well as NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory data lead Scott Davidoff.

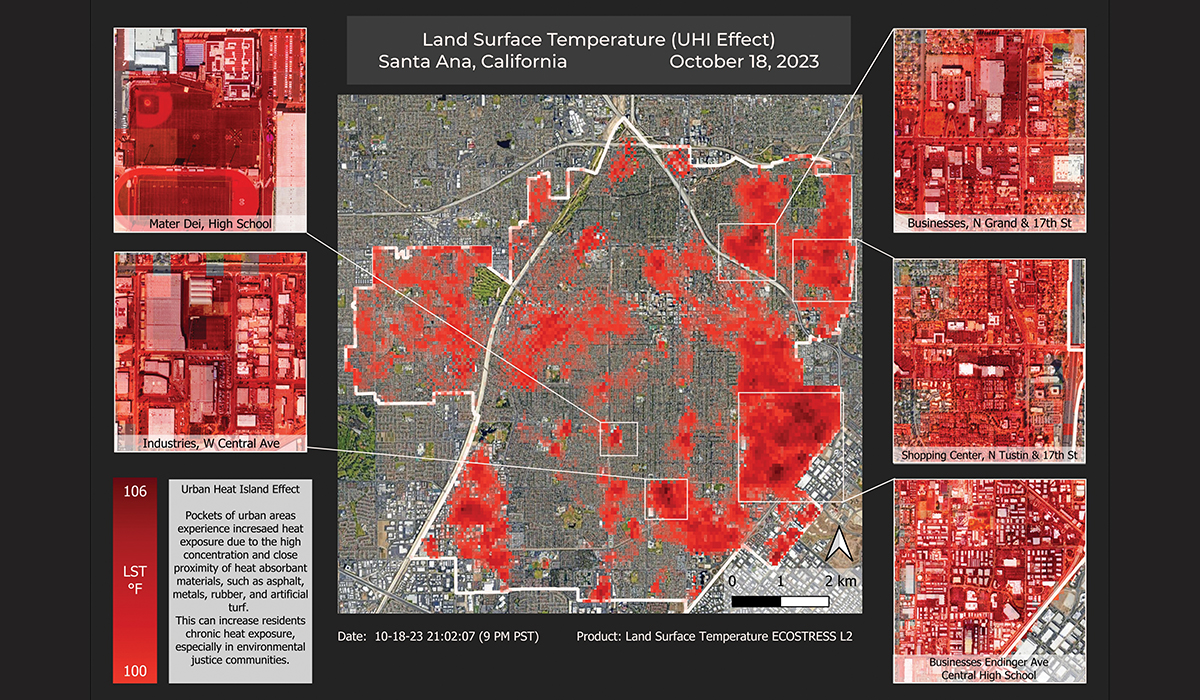

In pitching her data-driven project, first-year student Ashley Agatep ’27 uses artfully displayed temperature maps to show how the Urban Heat Island Effect is impacting residents of Santa Ana, about five miles from the Chapman campus.

“In Southern California, heat is an everyday part of our lives during the day,” says Agatep, an environmental science and policy major. “What if we can’t escape that heat, even at night?”

Agatep’s maps show patches of pink that turn deep red over infrastructure such as parking lots and turf sports fields.

“During the day, these concentrations of asphalt and turf soak up the heat instead of reflecting it back, and then at night they emit that heat into our homes,” she explains. “The chronic heat exposure deeply impacts the lives of residents, with lower-income and minority communities being affected at much higher rates.”

Keila Villegas knows firsthand how urban heat takes a toll. She grew up in Santa Ana and still lives in the densely populated neighborhoods mapped by Agatep.

“I live in an apartment complex with no AC system, and it’s hard to be at your best when you need a fan blasting in your face to stay cool,” says Villegas, water justice director for the Orange County Environmental Justice Educational Fund. “[Keeping cool] becomes somewhat of a marathon when it’s even hot at night.”

Feedback Helps Refine Project

After Agatep’s heat presentation during class, Paterno and Nielsen suggest tweaks to her messaging, but they also praise her presentation.

“I want to do this story for Voice of OC right now,” says Paterno, referencing a local news site to which Chapman journalism students contribute stories.

Later, Agatep would say that the pitch experience “taught me how to make my science more effective by communicating it to the public and to policymakers. I see that if I keep working on a project like this, it has the possibility of going out to people in Orange County.”

She’s also excited to get support for her work from the wider research community. Agatep and class colleagues Ruby Baldwin-Smith ’23 and Holland Hatch recently presented their work to NASA researchers at an ECOSTRESS team meeting.

The NASA experience was “nerve wracking,” Agatep admits, but she adds that many attendees approached her afterward to offer ideas for new applications of her research.

“A few months ago, as I was graduating from high school, I would have never thought I would be presenting to a NASA conference or having my work published on their website,” she says.

The Power of Research to Influence Policy

At the local level, Agatep’s project and others developed in the class also resonate with Maya Cheav ’22, a graduate of Chapman’s Environmental Science and Policy Program, who now is land and health director for Orange County Environmental Justice.

The neighborhood data Agatep collected reminds Cheav of a lead contamination project her team is working on in Santa Ana. After a local resident brought the problem to light, community partners helped expand the data set to include about 1,500 soil samples, Cheav says.

Along the way, advocates and policymakers learned that the contamination was disproportionately affecting lower-income neighborhoods and people of color.

“A big map showed the concentrations, and the city started listening to residents,” Cheav says. “That’s the power of research to influence policy.”

Back at Chapman, Goldsmith and Fisher are dedicated to seeing their course drive action, not just to address climate change, but to lift underserved communities and underrepresented students. They note that a dozen other universities have committed to creating a course modeled on theirs, and all of those schools are Minority Serving Institutions, including several Historically Black Colleges and Universities.

“The geosciences are the least diverse of all the STEM fields, and we think this project-based learning approach has the potential to improve recruitment and retention of a new generation of diverse geoscientists,” Goldsmith says.

“Many smart people have been working on climate change for a very long time, which begs the question: Where will new and different ideas come from?” Fisher adds. “The answer is from voices that have been historically excluded from participating in STEM.”