Sowers Of

Peace

Sowers Of

Peace

All over the globe, changemakers are embracing Whitney McIntyre Miller’s peace leadership model, feeding a global movement for systemic change.

“Visualize Peace,” the bumper sticker proclaims in a font designed to be read at 70 miles per hour. But what good is such a bromide without a blueprint for transforming the sentiment into action?

Enter Whitney McIntyre Miller, a leadership studies professor at Chapman University whose Integral Peace Leadership model is now steering communities toward systemic change in more than 40 countries.

Eight years after introducing her model, McIntyre Miller continues to enhance it through her research and teaching in the Attallah College of Educational Studies at Chapman — one of the few U.S. universities where programs in leadership studies and peace studies overlap. Along the way, McIntyre Miller has helped take the nascent field of peace leadership from visions and dreams to tangible steps for replacing entrenched systems.

“When I think of peace leadership, I think of intentional practices grounded in research-based work that challenges violence and aggression in whatever forms they take,” McIntyre Miller says. “There’s a need not just to undo systems, but also to build new structures that promote peace, equity and justice.”

She launched the model via a 2015 article co-authored with Zachary Gabriel Green. The authors frame peace leadership as “much more than what Einstein referred to as ‘the mere reduction of violence.’ It requires proactive, intentional practices to shift patterns of thinking, knowing and doing in the face of strongly held beliefs and cherished ways of being.”

“There’s a need not just to undo systems, but also to build new structures that promote peace, equity and justice.”

— Whitney McIntyre Miller

Beyond “Leadership as Person”

McIntyre Miller grounds her research in the work of numerous authors who elucidate the traits and examples of historic peace builders such as Gandhi, King, Lincoln, Mandela and Chile’s Michelle Bachelet. But as she developed her model, she knew it would need to go far beyond a focus on “leadership as person.”

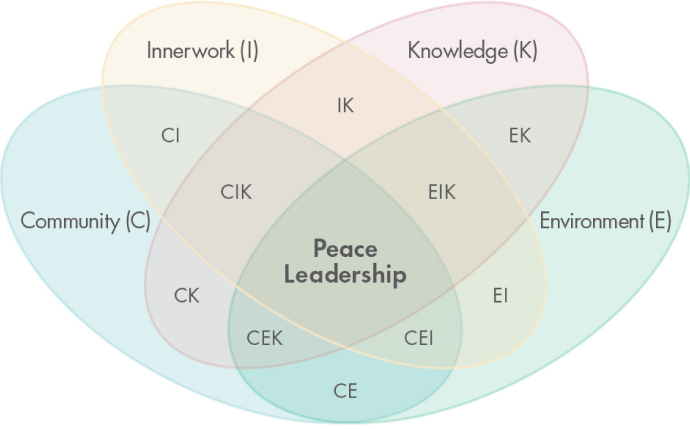

Through research and experience, including fieldwork in places like Sierra Leone and Bosnia-Herzegovina, McIntyre Miller ultimately built her peace leadership model on an integral theory structure called All Quadrants, All Levels, All Lines (AQAL) developed by American philosopher Ken Wilber.

Her model is designed to bring diverse theories and practices into a single framework for peace leadership impact. In essence, the model can inspire something like a peace-building checklist:

- Do the inner work so you embody peace in your personal life.

- Engage collectively to orient relationships and communities toward peace.

- Study theories, behaviors and practices of peace builders to provide evidence of peace in action.

- Apply strategies of group engagement to challenge societal structures.

Integral Peace Leadership

Whitney McIntyre Miller

The peace leadership model emphasizes four goals that, when combined and fully integrated, amount to an embodied practice with the potential to radiate outward.

But breakthroughs really become possible when all the elements come together over time to deepen experiences and create enduring connections.

“Each process in peace leadership is part of a nested and interwoven whole,” McIntyre Miller explains in the 2015 paper.

It didn’t take long for leaders and changemakers to embrace the professor’s integrated concepts, starting with Katy Lunardelli and Sylvia Murray of the Euphrates Institute.

“The model felt very true to the practices of our work,” says Lunardelli, executive director of the California-based nonprofit that equips, connects and uplifts emerging peace builders worldwide.

“It all clicked to have this research model that shows how inner work — embodying peace at the individual level — connects with outer work: interactions and relationships in the community,” Lunardelli adds.

Turning a Vision Into Peace-building Practice

The Euphrates Institute adapted McIntyre Miller’s model as it developed its Peace Practice Alliance, a six-month collaborative experience that explores peace leadership theories and practices while cultivating resilient peace-building communities.

More than 100 graduates of the program are now applying what they learned in leading organizations around the world, from California to Cameroon, Liberia to India, Afghanistan to Ukraine.

In Nigeria, trained peace builders are working with young girls who were kidnapped and sexually assaulted during the Boko Haram insurgency. Practices and trainings help victims “find a measure of peace after suffering such a horrible trauma,” McIntyre Miller says. “They’re also doing sensitizing workshops for the community so people learn about what their neighbors have gone through, and so the community itself can experience healing.”

McIntyre Miller and many of those who are putting her insights into practice recently met in Ghana for a Peace Leadership Forum, which featured focus groups, workshops and countless stories of peace-building progress.

Participants from the inaugural Peace Leadership Forum in Ghana.

“We’re seeing what we envisioned, which is a global movement of peace practice that’s growing and evolving,” Murray says. “Whitney’s theories are proving true in practice.”

Impact is being realized across a host of community and business sectors, including education, medicine and engineering. Nongovernmental organizations, churches and other community leaders are creating change in fields such as public health, conflict resolution, domestic violence, trauma healing, climate justice and even youth sports.

“I can’t tell you how humbling and amazing it is that this idea I put on a napkin in 2014 is now being used every day around the world,” McIntyre Miller says.

“We’re seeing what we envisioned, which is a global movement of peace practice that’s growing and evolving.”

— Sylvia Murray

A Broader Perspective Leads to Wider Impact

In Saudi Arabia, Miznah Alomair (Ph.D. ’18) is applying peace practice principles in her leadership role with the Alnahda Society, where she and her 70-plus employees work to empower Saudi women and families to succeed socially and economically.

“The work I’ve been doing with Whitney and my research in peace leadership have changed me as an individual,” says Alomair, who helped create a peace leadership curriculum during her time as McIntyre Miller’s first doctoral student at Chapman.

“I’ve been able to take my sense of empathy to a new level,” Alomair adds. “It’s not that I’m more peaceful; it’s that I have a broader perspective — I look at the wider impact of actions and I’m able to think more systematically about everything. I see how all the lines connect.”

“I look at the wider impact of actions and I’m able to think more systematically about everything.”

— Miznah Alomair (Ph.D. ‘18)

The lessons of peace leadership represent a cultural shift for Alomair’s organization, where the approach of previous leaders was more pragmatic and transactional rather than based in peace-building principles, she says. Progress is incremental as she helps prepare women to step into roles that used to be unavailable to them.

There’s optimism that succeeding generations will be especially open to change.

“As I connect with the youth, I continue to believe this is the right fit. There are great opportunities to impact societies at different levels and in more powerful ways,” Alomair says.

Cultural transition is also at the heart of the work being done by Nick Irwin (MA ’17, Ph.D. ’24), who includes peace leadership research in his Chapman doctoral dissertation. He’s also a student of the Euphrates Peace Practice Alliance.

Irwin retired in June after 20 years in the Navy, and now he’s applying peace leadership lessons as he works with college students who are military veterans — many of whom struggle to adapt to campus life.

“In the military, things tend to be black and white — us vs. them,” Irwin says.

Peace leadership practices help with self-regulating responses, “so we can manage our stress and respond rationally,” he adds. “Connecting the personal to the interpersonal is all part of building positive peace strategies.”

As a mentee of McIntyre Miller, he has seen the best of peace leadership in action, he says.

“Whitney embodies peace leadership,” Irwin enthuses. “After defending my dissertation proposal, I told her I wanted to take summer school to maximize my veteran’s benefits, and she advocated to make that happen. As we say in the Navy, she rogered up, which isn’t a surprise because she’s continuously supportive and is always looking for ways to collaborate.”

Refining the Model Through Ongoing Research

These days, McIntyre Miller continues to explore opportunities to refine and apply her Integral Peace Leadership model. She and colleagues published four papers on peace leadership in 2022, including one, co-authored by Alomair, for the journal Peace Psychology titled “Understanding Integral Peace Leadership in Practice: Lessons and Learnings From Women PeaceMaker Narratives.”

Another paper, written with researcher Anna Abdou, shares stories of peace leadership growth, training and development in K-12 educational settings. In addition to their research, the authors are working with teachers and administrators to share peace leadership practices and develop curricular materials.

Financial support for this project comes from Attallah College’s Solutions Grants, which support faculty research that addresses a specific local need, as well as from the American Psychological Association’s Peace Psychology Division. In addition, grants from the Miner Anderson Family Foundation support the school training project along with a new Peace Leadership Collaborative, which will bring together a broad range of peace leaders to network and share resources.

Also on the horizon for McIntyre Miller is a book of peace leadership narratives, building on her work during the Ghana conference.

“The plan is that each of these stories will illustrate the Integral Peace Leadership model — how it actually works in practice and what it looks like for people,” she says.

As the seedlings of peace leadership planted by her model continue to propagate, McIntyre Miller also works to root the lessons in her own life.

She loves that the story-gathering and other research she does take her to frontline peace-building communities in Ghana and beyond. But she knows that the work begins in her home and classroom.

“Really, it’s a fairly idealistic, optimistic model, and we acknowledge that it’s hard to do this work — hard to do all the pieces, and especially hard to do all of them well,” she says.

“So I try to use this at an interpersonal level all the way up to how we might implement the Paris Climate Accords so they aren’t just signatures on a document. I want to find a place for it in all of my decision-making — how I spend time in this space to give to the work and to the world.”

Local peace leaders from all over West Africa and the United States participate in the forum in Cape Coast, Ghana.

Local peace leaders from all over West Africa and the United States participate in the forum in Cape Coast, Ghana.

Local peace leaders from all over West Africa and the United States participate in the forum in Cape Coast, Ghana.

Story by Dennis Arp

Design by Cindy Harvard, Julie Kennedy and Vivian To

Video by the Euphrates Institute

Media Contacts

Strategic Marketing and Communications

1 University Drive

Orange, CA 92866

Contact Us

Newsroom Site

Your Header Sidebar area is currently empty. Hurry up and add some widgets.