History is always personal, but sometimes it can hit very close to home.

That was the case for Stephanie Takaragawa, Chapman University associate professor of cultural anthropology, when she was a college student and first learned about the imprisonment of Japanese Americans by the U.S. government during World War II.

In 1942, 120,000 Japanese Americans, most of whom had been born in the United States, were evacuated from their communities and transported to relocation camps around the country due to unfounded concerns that they might pose a public threat in a time of war. Living conditions in the camps were grueling, with communal housing, little privacy and insufficient insulation against extreme temperatures. Entire families lost their homes, their livelihoods and their freedom.

“I learned about it and then I went home and I said to my parents, ‘I learned about the Japanese American internment and it makes me wonder where our family was during this time.’ And my parents were like, ‘Do not ever talk about this to your grandparents. They’ll be very upset. Yes, the family was interned,’ and that was it,” she remembers.

More than three decades later, Takaragawa still regularly encounters students in her classes who have never heard about the incarceration or have only the barest notion that it occurred. Even though the 1988 Civil Liberties Act mandated instruction about the incarceration as part of school curricula, it is still a largely overlooked topic in primary and secondary education.

Putting History On Display

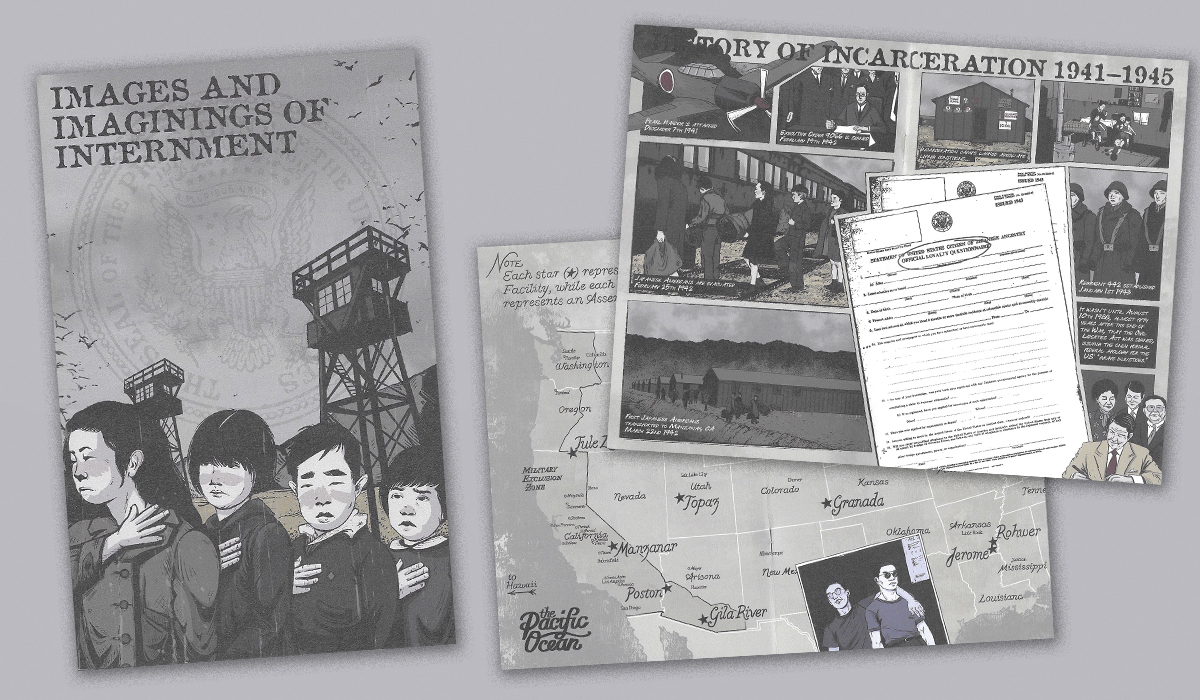

In 2022, Takaragawa was awarded a $124,906 grant from the California State Library’s California Civil Liberties Public Education Program to produce an exhibition that tells the story of incarceration using art created by the internees themselves. The exhibition, “Images and Imaginings of the Japanese American Internment: Comics and Illustrations of Camp,” can be visited in several locations on the Chapman University campus, and it includes an online resource that is designed to teach about the Japanese incarceration through photo galleries, interactive features and discussion questions.

The project evolved from a discussion in one of Takaragawa’s courses at Chapman. As the class delved into biased depictions of Japanese Americans in WWII-era comic books — Superman, for example, once visited an incarceration camp to root out “anti-American” activities — Winston Andrews (MA ’21) asked about comics produced inside the camps. The question turned into a class project for Andrews, and that project turned into the exhibition of incarceration art currently on display on Chapman’s campus.

A Firsthand Look At Japanese Incarceration

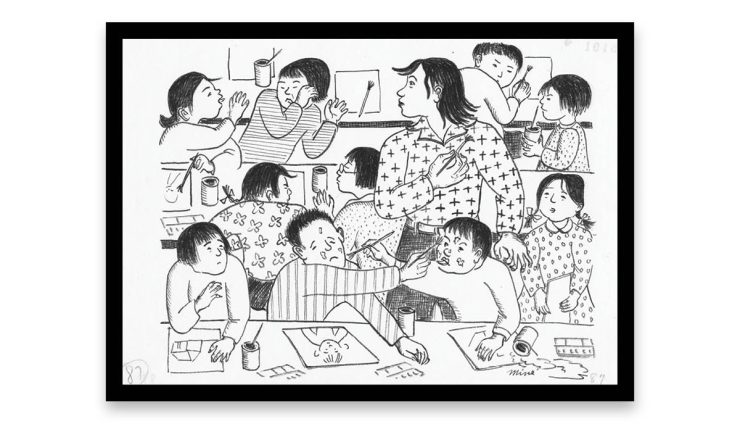

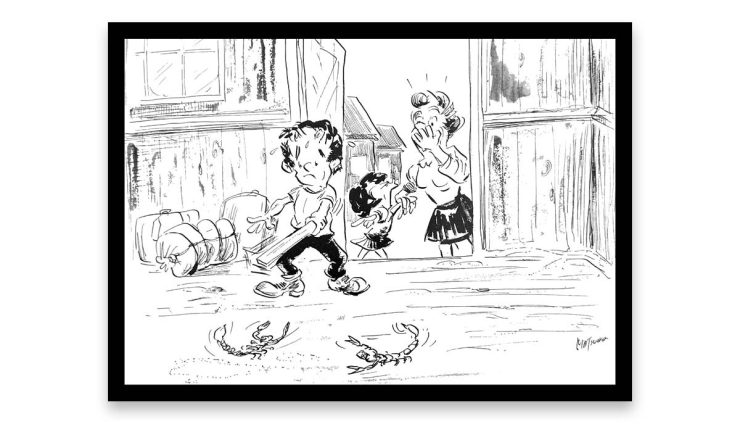

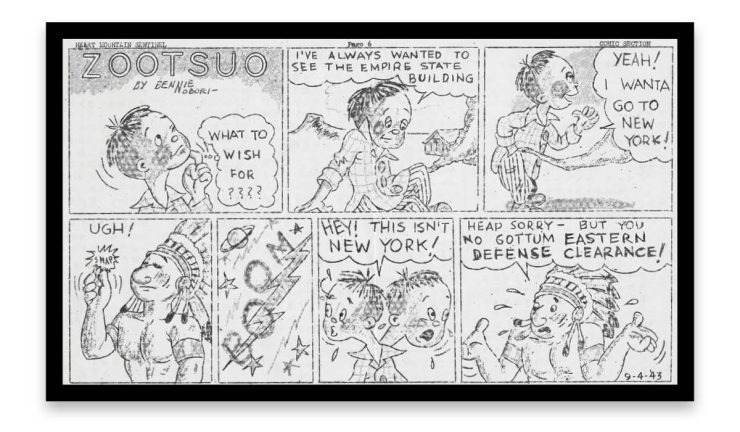

The comics and other artwork featured in the exhibition offer a unique, firsthand glimpse into what life was really like behind the barbed wire of the incarceration camps.

“The comics that were in the different camp newspapers are ways in which people could enact some form of resistance,” Takaragawa says.

The comics were a way for people to communicate a feeling of community while simultaneously acknowledging the situation they were in, without being outwardly critical of the government and being potentially identified as disloyal.

Jan Osborn, associate professor of rhetoric and composition studies, and Jessica Bocinski, registrar of Chapman’s Escalette Permanent Art Collection, worked with Takaragawa and Andrews to develop the online curriculum and design the virtual exhibition. Early versions of the site were presented to focus groups consisting of teachers and students at nearby schools.

“I was genuinely surprised that they knew so little,” Osborn says. “I knew I had never learned about this in my own education at all, and I thought that had changed … It’s just not a history that has made it into the curriculum in a meaningful way yet.”

Takaragawa hopes that featuring comics will make it easier for students to connect with what can be a difficult subject.

“Sometimes it is easier to have a conversation around images than it is around a textbook,” she says.

Some of the Japanese American artists whose work is featured in the exhibition include:

Graphic novels continue to be a powerful means for Japanese Americans to examine the ongoing impact of incarceration, including titles such as “Displacement” by Kiku Hughes, “Stealing Home” by J. Torres and David Namisato, and “They Called Us Enemy” by George Takei, Justin Eisinger and Steven R. Scott.

The “Images of Internment” exhibition will be on display at Chapman University through December 2023. View the online version.