For people in countries with advanced economies, using an ID card to open a bank account, vote and get a loan or a job is often taken for granted. Even traveling abroad to the World Cup requires an ID. Chapman University Assistant Professor Jonathan Hersh is working to bring IDs to more remote areas like western Africa.

For people in countries with advanced economies, using an ID card to open a bank account, vote and get a loan or a job is often taken for granted. Even traveling abroad to the World Cup requires an ID. Chapman University Assistant Professor Jonathan Hersh is working to bring IDs to more remote areas like western Africa.

Hersh, who teaches in Chapman’s Argyros School of Business and Economics, became interested in using economics and data analysis to solve global challenges while working on his dissertation at the World Bank a decade ago.

At the time, the capabilities of computer algorithms to analyze satellite images were advancing rapidly, and the World Bank was conducting on-the-ground surveys to monitor and alleviate global poverty.

The challenge was that those surveys were costly and didn’t cover a significant part of a country’s population, Hersh says. And countries with developing economies often lack comprehensive birth records for economic, logistical or cultural reasons.

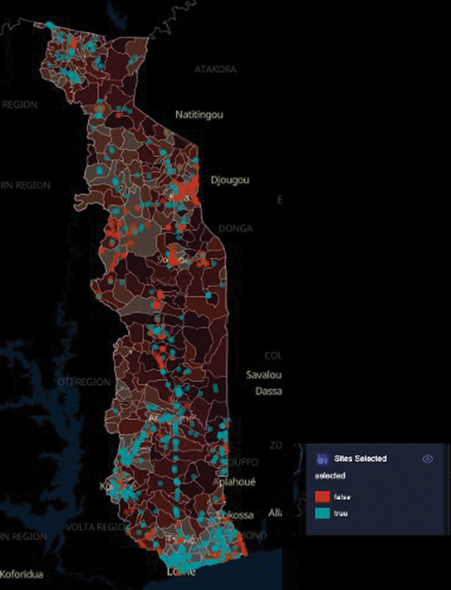

When the pandemic hit, governments wanted to quickly deliver economic aid to vulnerable people. The World Bank asked Hersh if he could help identify vulnerable populations in Togo, a narrow country of more than 8 million next to Ghana. He and a graduate student analyzed satellite images to pinpoint where these people were clustered and helped deliver economic transfers to them.

of ID cards.

According to the World Bank, around one billion people worldwide don’t have a foundational ID. This makes it hard to get a loan, vote and get a pension. Some of the people Hersh worked with in Togo asked if he could help figure out how to get an ID to everyone in the country – work supported by the World Bank’s Identification for Development (ID4D) Initiative. Hersh had funding and a robust server that could handle the data processing, so he agreed to help.

“Implementing a unique ID system is one of the primary steps that we can take for a country as they’re trying to get on that first ladder rung of development,” Hersh says.

IDs are a “bit of a chicken-and-egg” situation in developing countries.

“We know everyone should have one – it helps individuals who want to get a loan for their business, get a job or vote. But how do we get to the point where most people possess an ID card, prompting banks and employers to request it?” he says.

Creating IDs is easy – officials use portable kits to make them using a photo and fingerprints. It’s delivering one to everyone in often remote areas that’s challenging, Hersh says.

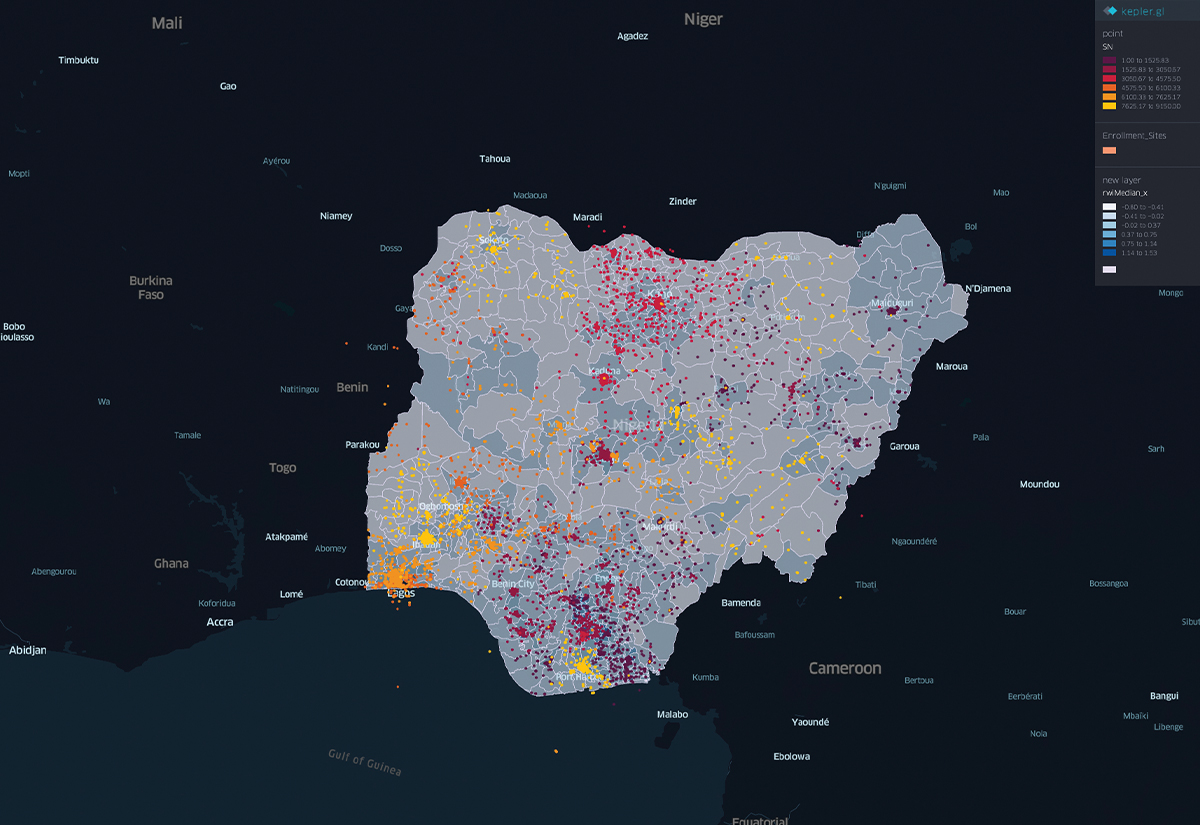

His student research team – including Joshua Anderson ’20 (MS ’22), Erin Lee ’22, Connor Lydon ’22 and former Chapman graduate student Kushal Reddy – used publicly accessible satellite data to develop alternative ways to track a country’s vulnerable population. From there, Hersh’s team uses the OpenStreetMap database to find the best places to set up ID registration, like markets, malls, government centers, health clinics and places of worship.

Knowing where vulnerable people are helps officials with limited resources to serve the greatest number of people and limit residents’ travel time. The same algorithm – known as the facility location problem – is used in business logistics and humanitarian work, Hersh says.

“We solved this using many of the same skills around math, algorithms and data analytics that we teach in our classroom,” he says.

He adds, “The fact that we’re addressing these challenges using completely open methods means that this problem can be solved anywhere in the world.”

To date, Hersh and his team have presented their ID distribution framework to officials in Togo, Côte d’Ivoire and Nigeria — Africa’s most populous country at over 200 million people.

Togo’s minister of digital economy and digital transformation, Cina Lawson, expressed admiration for the presentation, and Nigerian officials incorporated it into their ID registration strategy, Hersh says.

“Our aspiration is that a substantial number of people will have access to bank accounts, the ability to work formally, and have the chance to exist in ways they’ve not previously experienced,” he says. “This is happening in collaboration with operational partners who can work on the ground.”