What do you do when an intricate ecosystem of trees and roots disappears?

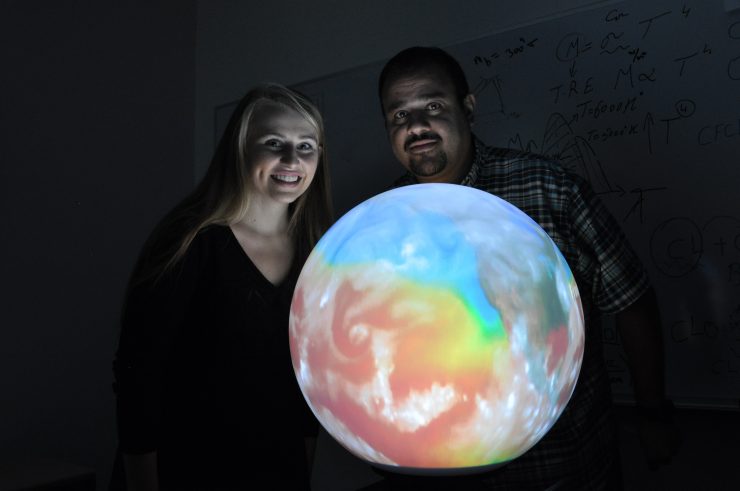

This was the mystery presented to researcher Hesham El-Askary, Ph.D., a professor in Chapman University’s Center of Excellence in Earth Systems Modeling & Observations.

He was alerted to the missing mangroves by NASA and U.S. Geological Survey joint program Landsat satellite images of the Arabian Gulf’s Jubail conservation area. They showed startling discrepancies as to how much of the coastline was covered in native mangroves — trees that support diverse ecosystems and thrive in salty conditions.

From 2000 to 2014, it looked like the entire forest had disappeared.

It turns out that while Landsat images make it easy to recognize variations in topography, they are far less effective at revealing differences in vegetation. As researchers studied bird’s-eye views of the mangrove distribution area, the submerged mangroves were being confused with salt marshes and macro algae.

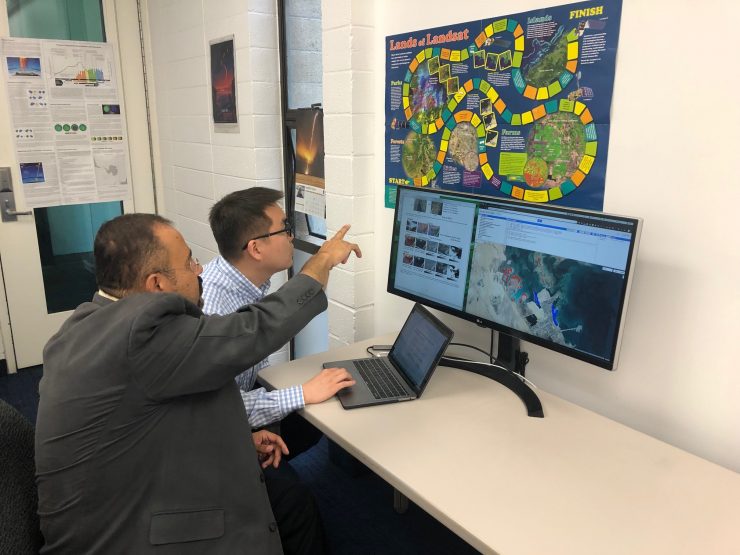

This is where the artificial intelligence comes in. El-Askary and his team used programs known as the Submerged Mangrove Recognition Index (SMRI), the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and Classification and Regression Trees (CART) to gain some clarity.

The programs allowed researchers to sort through the visual density in satellite images and determine which part of the Jubail coastline was mangroves and which part was marsh, El-Askary says.

CART was 95% accurate in identifying mangroves, while the other programs achieved 90% accuracy. With this honor-roll-worthy lineup of programs, El-Askary and his team were able to “find” the forest through its trees.

The team’s findings directly support conservation efforts by the Environmental Protection Department of Saudi Aramco, Saudi Arabia’s state oil company. The research will also be used by the Center for Environment and Water of King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals in Dhahran.

“Both are working closely with us on the preservation of these marine ecosystems,” says El-Askary. “Our mapping techniques will be key in establishing a better understanding of how they are affected.”

Going forward, the Chapman team’s findings are likely to be applied wherever Mangrove forests are studied – especially to validate USGS datasets, since that information is generally considered a baseline for mangrove mapping and monitoring.

The team’s approach of combining traditional AI algorithms with knowledge-based expertise may also be applied to solve satellite-data issues in other areas of research, such as analyzing crop growth, planning cities and monitoring traffic patterns.

And for the time being, mangrove forests of the world remain safely in sight.

Disappearing Trees

You can find mangrove forests in 123 countries – most of them in tropical latitudes. The arid Middle East accounts for about 0.4% of global mangroves. These coastal trees and shrubs play an important part in regulating climate by sequestering atmospheric carbon. They also help moderate extreme weather events such as cyclones and tsunamis.

About 90% of global mangroves are critically endangered. They are nearing extinction in as many as 26 countries.