The proper names preferred by a tribe of native people living in the Peruvian Amazon are lovely and captivating, even in their English translations. “Shining Anaconda” and “Proud Bird” are just two examples.

But to the Spanish-speaking officials who manage Peru’s public records, the spellings and pronunciations of those names in the indigenous Shipibo-Konibo language seemed strange and difficult to spell or pronounce. So administrators there have long pushed members of the indigenous tribes to register their newborns with Spanish names — monikers that would be printed on identity cards and follow them through life, from school records to death certificates.

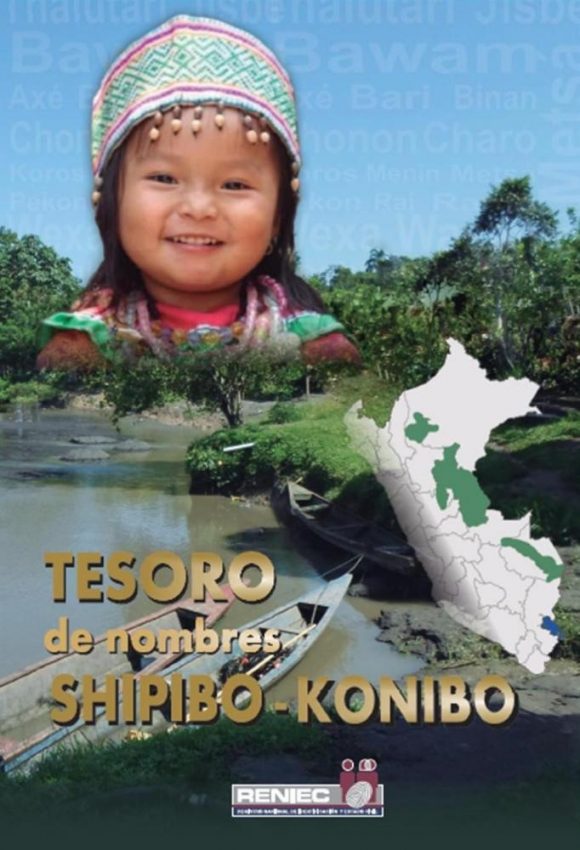

Now that is changing. And to help officials and educators better understand the naming tradition, the government of Peru enlisted the help of Chapman University Professor Pilar Valenzuela, an expert in Amazonian languages. They asked Valenzuela for both a research study and practical recommendations to help bring what many Amerindians call their “true names” into official use. The result is the book “Tesoro de nombres Shipibo-Konibo,” which roughly translates to “Treasure of Names of the Shipibo-Konibo.”

Honoring Identity

The new respect for the pre-Columbian names, called janekon, is significant, says Valenzuela, Ph.D., who teaches in Chapman’s Department of World Languages and Cultures. The practice of requiring Spanish or Christian names is a remnant of the Colonial era when the Portuguese and Spanish subjugated the indigenous peoples.

“I’m so glad that there is such a big change ideologically,” Valenzuela says. “It’s about the rights of indigenous peoples to be able to maintain their own languages, identities and names for places and people.”

Her catalog and study of more than 1,000 names also allowed Valenzuela to provide further evidence supporting anthropologists’ theories that the earlier Shipibo (shih-pee-boe) organized themselves into patrilineal clans, often identified with animals such as Jaguar, Snake or Parrot. The names she studied were all compound, with the first portion usually reflecting the clan animal.

Language Conveys History

Such research not only helps strengthen endangered languages and cultures but also can offer scientists insights into different worldviews because language is laced with unique information accumulated over centuries by its speakers.

“Names and language are part of the core of people’s identity. The special knowledge you have, the special connections you maintain to nature, animals and especially, the plants. Plants such as ayahuasca occupy a central place in indigenous spirituality,” she says. “Nowadays it is not uncommon to name a girl after her maternal grandmother and a boy after his paternal grandfather. However, it may also be the case that a child is given the name of a spirit that appeared during an ayahuasca vision.”

This latest project dovetails with Valenzuela’s ongoing research, supported by the National Science Foundation, to document the language of the Amawaka, a tribe living in the Amazon forests of Peru and Brazil. The term Amawaka means “Children of the Capybara.” The collaborative team led by Valenzuela will include student researchers from Chapman and the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru.

‘Big Cultural Change’

For the moment, though, Valenzuela will focus on promoting the mainstream use of “true names” and is helping to plan a radio spot to encourage the practice among the indigenous people, who have typically used the names just among themselves. She is delighted that in addition to an official release party in the capital city of Lima, the National Registry of Identification and Civil Status also held a special unveiling of the book in the Amazonian city of Pucallpa, on the banks of the Ucayali River, home to the largest population of Shipibo-Konibo.

“The very office that would deny them the use of these names in the past is now actually acknowledging these names and making it easier to use them,” she says. “It will be a big cultural change.”

Display image at top/Pilar Valenzuela, at center in blue, with a soccer team from the community of Paoyhan.