“The new Center for Science and Technology will allow us to expand the range of different questions we can ask. We already are asking important questions, and doing important research to answer them. But the new Center will allow us to be more expansive in our exploration. I think that’s true of all Chapman researchers.”

–Andrew Lyon, Ph.D., dean of Chapman’s Schmid College of Science and Technology, on the new Center for Science and Technology

Andrew Lyon’s research world revolves around stretchy bits of science 10,000 times smaller than a human cell. But those nanoparticles hold oversized promise as breakthroughs in the lives of everyone from trauma victims to cancer patients.

The microgels in Lyon’s lab at Chapman University may ultimately be the building blocks for an IV injection that stems uncontrolled bleeding. Or they may get commercialized as a topical powder that first responders pour into a wound to get blood to clot. Then there’s the science fiction scenario: They become a preemptive product that safely flows through the bloodstream of soldiers or others headed into harm’s way so if they sustain a traumatic injury, protection is already in place.

Closest to market is a product that aids patients whose blood doesn’t clot properly because they’re undergoing chemotherapy.

“If we can use these polymer nanoparticles to commercialize artificial platelets, we can change bleed rates and improve models of survivability,” says Lyon, Ph.D., dean of Chapman’s Schmid College of Science and Technology. “That’s why we’re so excited.”

To see Lyon at the whiteboard in his Hashinger Science Center office is to see him totally in his element. After 18 years of exploring foundational things like condensed-matter physics and how proteins and DNA move inside a cell, the science of polymer nanoparticles pretty much flows through his own genetic makeup.

“The artificial platelets and how they work is kind of like taking an Isaac Asimov Fantastic Voyage,” Lyon says.

Using an erasable marker, the dean creates interlocking loops, squiggles and arrows as he diagrams the science of his project at the molecular level.

The particles at the heart of the research feature a coil-like structure inside a fibrin mesh that elongates and stretches to allow for multiple binding sites, mimicking the architecture of natural platelets.

Lyon uses an analogy: “If you’re putting a stack of papers together, 20 staples are better than one,” the dean says. “So that’s part of the secret sauce here – a super stretchy polymer that we’ve designed as the body of an artificial platelet.”

Once the platelets bond to a clot, they pull the fibrin polymer in, “almost like a little muscle,” Lyon says. “That makes the clot more stable so the body can step in and regenerate normal tissue.”

These days, Lyon’s team is focusing on scale-up of the project to produce more of the polymer and ensure consistent quality. That will allow for further testing and, ultimately, commercialization.

“Going from a gram of polymer to making 50 grams takes a lot of science and engineering,” he says.

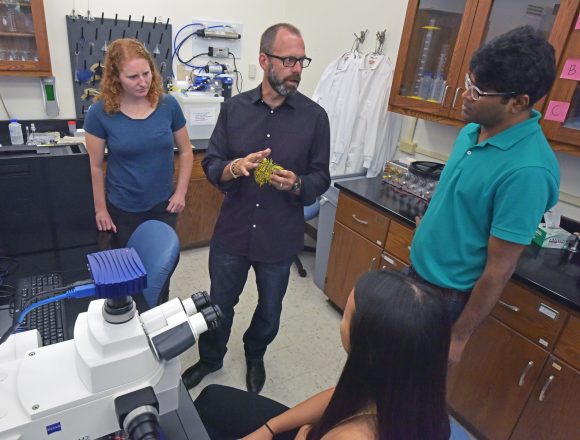

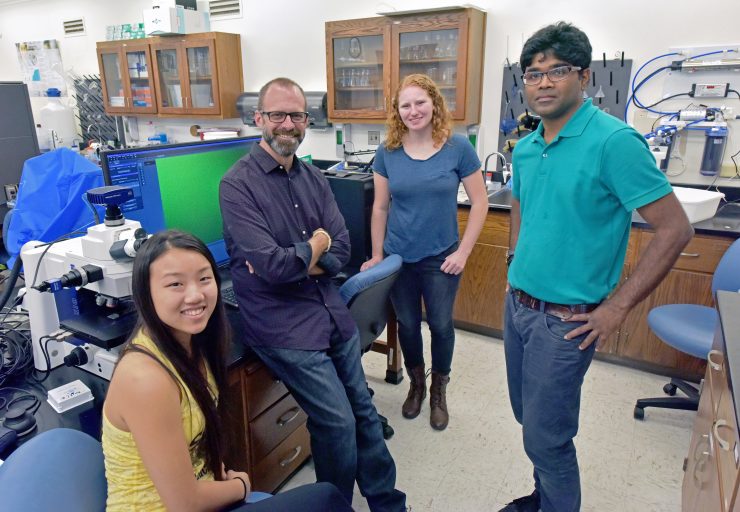

This endeavor is hardly Lyon’s alone. His team at Chapman includes research scientist Dr. Molla Islam, as well as Chapman graduate and student researchers Sonia Djafri ‘17, Anne Roffler ‘17, Rachel Nguyen ‘18 and Alyce Baughman ‘18. This summer, the team also features the contributions of high school students Vivian Yip and Maddie Tumbarello.

Meanwhile, collaboration crosses campuses and time zones, as Lyon is one of four main investigators on the project. The others are Thomas Barker, Ph.D., a professor of biomedical engineering at the University of Virginia; Ashley Brown, Ph.D., a professor at North Carolina State and UNC-Chapel Hill specializing in regenerative medicine and pharmacoengineering; and Wilbur Lam, Ph.D., of Emory University and the Institute for Electronics and Nanotechnology at Georgia Tech.

It was over a cup of coffee four years ago that Lyon and Barker launched the joint research effort. At the time, they were pursuing a $13 million grant from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) for a field-trauma application of their research. Although they didn’t get that grant, the process “made us think deeply about how the technology could be successful,” Lyon says. “So when we got in the lab and started building something, we had a good idea what the design features would be.”

Now Lyon’s team is part of a five-year grant from the National Institutes of Health, and the hope is that the grant will culminate with team members gearing up for a clinical trial.

“All the initial studies are positive,” he says.

As the project advances, transforming from a broad concept discussed over coffee into a biomedical breakthrough, Lyon takes a moment to reflect on the ups and downs along the way.

“I think of science as this constant oscillation between fascination and frustration,” he says. “What you’re really striving for is spending more time on the fascination side than on the frustration side.”

Sure, there are frustrations as team members try to translate research into a reproducible product and then commercialize it. But, oh, the rewards on the fascination side when “you learn something about nature that no one has ever known before,” Lyon says.

“The exciting thing is that we continue to challenge this technology, and now we can see the light at the end of the tunnel,” he adds. “We can see how this will have a positive impact on people’s lives.”

To support Dean Lyon’s research or to name his laboratory, please contact Lauren Lee at 714-289-2032 or lkenny@chapman.edu.

Photo display at top/The polymer research team at Chapman is led by Schmid College Dean Andrew Lyon, second from left, and features high school students Vivian Yip, left, and Maddie Tumbarello, as well as research scientist Molla Islam, right.

About the Artists and Their Designs

Opening a window to process, we asked our alumna artists to tell us about the pages they created for this issue of Chapman Now and how the experience compares with their other design work. Here is Deena Edwards ’14 and her insight on designing “The Science of Breakthrough.”

Calling it “a huge challenge,” Edwards pivoted from her daily software-development duties for WeWork to help us interpret the nanoparticle research of Andrew Lyon, Ph.D., and his science team at Chapman.

She leaned on tools from her Chapman studies.

“My traditional process kicked in,” Edwards says. “I did research about the content and I gathered some inspiration pieces. Illustration became a big part of this. I wanted to represent what goes on within a cell, and I wanted colors that would carry the idea of cells moving through the bloodstream.”

The resulting design mixes vibrant hues with “clean white space,” creating a balance that her Chapman professors can appreciate.

“I was definitely inspired by the content,” Edwards says.

And in the end she met her own fundamental measures of success.

“It’s about making things easier for users so they can have a good experience,” she says. “Solving problems in an organized way – that’s what I really like about design.”

Edwards’ full design for “The Science of Breakthrough” can be viewed below, online or on pages 10-12 in the summer 2017 print issue of Chapman Now.

Add comment