With a swipe of his hand, Professor Frank Frisch uncovers the inner workings of a human body. Skin and muscles disappear from the cadaver before him, and his students marvel at the skeletal structure instantly revealed.

“Remarkable, isn’t it?” says Frisch, Ph.D. His students respond with nods and appreciative murmurs. Soon they, too, join the exploration, adding organs back in or pausing to open the top of the skull and peer into the brain.

The process is easy because this body is actually a virtual three-dimensional cadaver digitally recreated and displayed onto a simulated dissection table that works like a large computer touch screen. Chapman University students were introduced to the state-of-the-art technology in the fall semester when the Crean College of Health and Behavioral Sciences overhauled its anatomy lab, equipping it with three of the virtual dissection tables widely used at medical schools.

The tables don’t eliminate the value of cadavers, which students still work with in graduate programs at the Rinker Health Science Campus, Frisch says. But for under- graduates, the interactive technology is a good way to quell anxiety surrounding a first scientific encounter with a body.

“For some students, because of the early instructions about the lab and environmental practices, about the propriety of handling human tissues and about the reverence for this human body, they become fearful about making mistakes. They worry about damaging the specimen,” he says. “With this technology, any mistake is rectified with the push of a button. And that allows students to be, not cavalier but less fearful. And that’s a barrier down. Now the focus is on learning.”

They intuitively grasp the technology.

“The students pick it up fast,” he says. “They write quizzes and store them on the table.”

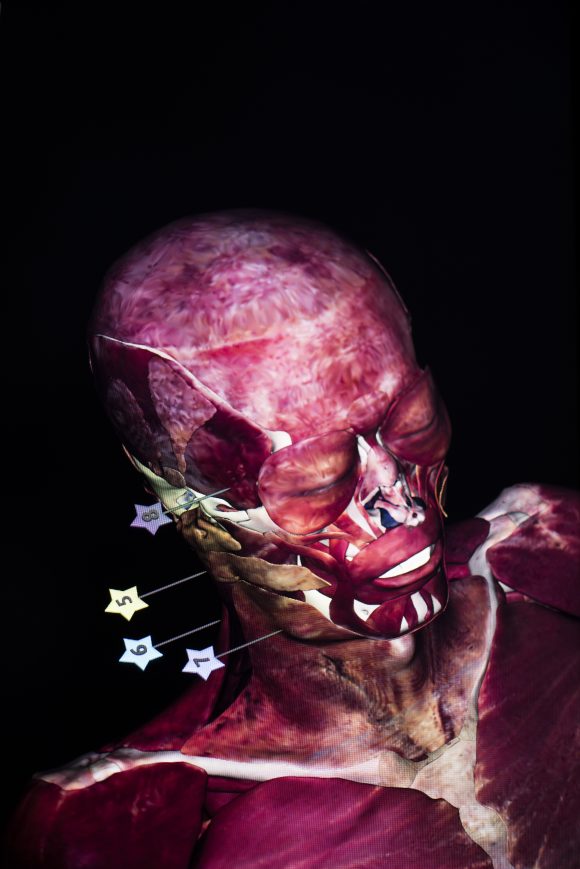

Respect for the donor is still important, though. During an introduction to the table, Frisch tells students that the young man whose body they are studying was a 33-year-old male who died of leukemia and in the last stage of his life agreed to have his body dissected after his death and the images reconstructed into the virtual cadaver they see before them. A female cadaver is also included in the software.

The tables are made by the Silicon Valley medical imaging firm Anatomage and function like giant iPads or smart phones. When the life-size body image is displayed, it nearly fills the table. Simulated dissections can be performed with finger motions. Students and teachers can zoom in and out on a specific body part, enlarging it for a close-up examination. Selected body systems can even be hidden from the screen, allowing a focused look at one system or perhaps a combination. For example, just the musculature and nervous system can be viewed together and their unique relationship examined.

Unlike with a real cadaver, the entire body image can be easily rotated or shifted.

“If I had to manipulate a body in a traditional lab, it would take three or four of us to do it,” Frisch said.

Which brings him to this point. Although the three tables required an investment of nearly $300,000, traditional anatomy labs are expensive to maintain and manage because of health, environmental and handling regulations. The matchless hands-on experience of working with real cadavers will always be needed, but the virtual experience – which includes student access to online study guides and programs – is incredibly valuable, he said.

“When I first heard about the tables, I was against getting them. Cadavers are so great,” Frisch said. “But I have changed my position. I think we’ve hit a home run with the virtual lab.”

Add comment