Memorial Hall was crowded on that chilly late-fall night, as it often was for events in the popular Artist Lecture Series. During the 1961-62 school year alone, the series attracted historian and journalist William L. Shirer, poet Ogden Nash and author Aldous Huxley, among a handful of others. The December speaker didn’t exactly stand out in that company. The CEER yearbook would later identify him simply by name and occupation: “minister.”

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had not yet written his Letter from Birmingham Jail, nor delivered his I Have a Dream speech, and he was three years to the day from being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Still, for some in the audience, the man who stepped to the podium on Dec. 10, 1961, was already a heroic figure. And the experience of hearing him eloquently make the case for racial equality, social justice and nonviolent resistance made that evening a seminal moment in their lives.

Dennis Short ’64 (M.A. ’85) and Mark Messer ’62 are two such people.

TOWARD FREEDOM

As student chairman for the Artist Lecture Series, Messer played a key role in bringing King to campus. He had learned about the emerging civil-rights leader from articles by Glenn Smiley, who worked on the Montgomery bus boycott, and by reading King’s recently published book Stride Toward Freedom.

“I devoured that book,” said Messer, Ph.D., who is retired from a faculty position at UC Santa Cruz and still lives in that area. “King’s work and thoughts on nonviolence and social action helped channel the direction of my undergraduate study,” such as courses in ethics and philosophy with Dr. Bert C. Williams ’35, and in religion with Professors Guy Davis, Ron Huntington and James Christian.

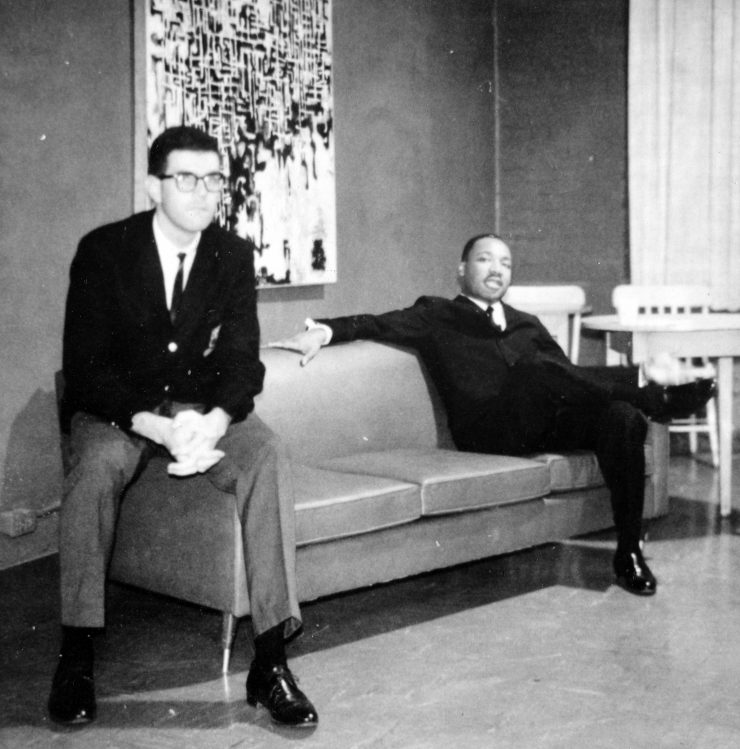

Mark Messer ’62 shared a couch with Dr. King as he helped lead an informal Q&A session after the civil-rights leader’s speech, but Messer says he was so self-conscious that he remembers little about this part of the evening.

After the talk came a question-and-answer session with students and faculty, where Messer was tasked with fielding questions from students while sitting next to the man he greatly admired.

When the Q&A session was through, Messer drove King to his hotel in Los Angeles. This was before King started traveling with a security detail, so it was just the civil-rights leader and the senior sociology major alone in Messer’s yellow-and-cream-colored ’55 Plymouth Belvedere for the 40-minute trip to Downtown L.A.

Messer was impressed with King’s politeness and humility as his passenger asked him several questions about his own studies. Messer had just been accepted to do graduate study at the Boston University School of Theology, so the two talked about King’s experience at BU, “and he offered me advice on what to expect.”

Then Messer mentioned he had recently written a paper on redemptive suffering, a concept introduced to him by King’s book. Specifically, Messer recalls, he and King discussed the contrast between the notion of the redemptive quality of self-inflicted suffering as expressed in Roman Catholic theology, and how absorbing suffering from an aggressor without returning the violence can have a redeeming effect on the aggressor himself.

“Dr. King generously left me with the feeling that together we had engaged in a genuine intellectual exchange,” Messer said.

At the hotel, just before the two parted, Messer asked King to autograph a small paperback titled The Measure of a Man. King wrote, “To Mark – Best wishes at Boston, with warm personal regards, Martin Luther King.”

While Messer didn’t end up doing his postgraduate work at BU because Northwestern gave him a more generous fellowship, that doesn’t qualify as a regret. This does: In an impulsive moment seven years later, he gave the autographed book to one of his students at UC Santa Cruz after the student said King was also his source of inspiration.

Still, he will always have the moments that matter most –sharing a couch with King as he relayed questions from his peers, and then engaging in a reflective conversation during a car trip that is still packed with emotional and intellectual power, at least in Messer’s mind.

“What a night,” he said in a recent moment of reflection. “To this day, Dr. King is my most cherished hero.”

A POWERFUL PRESENCE

“I was mesmerized,” Dennis Short says of the time he spent with Dr. King, whose bust became the first of many to grace Chapman’s campus.

Like Messer, Dennis Short served on the committee that brought King to Chapman, and he had also been already influenced by King’s writings and teachings.

“I was a very active student on civil-rights issues,” said the Rev. Short, Ph.D., who was chaplain at Chapman in the 1970s and later served as minister at Covina Christian Church. “I picketed a Woolworth store in Santa Ana because they refused to serve African Americans.”

So when King agreed to speak at Chapman, “I was very excited,” Short said. “There were very few African American students at Chapman then, but the event seemed to have support from the faculty and the students.”

And the speech itself?

“It was the most moving speech I had heard up to that time in my life, and probably since then, as a matter of fact,” Short said. “I had heard him on the radio and seen him on TV, but you didn’t get a sense of his powerful presence until you met him. I was mesmerized.”

Like Messer, Short also shared a more personal moment with King. He, Professor Netter Worthington, who was chairman of the Artist Lecture Series committee, and another faculty member drove King to the airport for his flight home.

The other professor was less than sympathetic to the civil-rights movement and made his feelings known, Short recalled. “I think he was from the South. Perhaps he felt threatened. I felt embarrassed.”

Throughout the conversation – about living under Jim Crow laws and the struggles faced by his family – King “had an amazing sense of calm,” Short said. “You could feel his confidence that he was doing God’s will and was calling others to do the same.”

After graduating from Chapman in 1964, Short’s own call took him to Indianapolis, where he attended Christian Theological Seminary. He was in his second year when he saw televised images of King’s march from Selma to Montgomery in Alabama. He watched as police on horseback rode into and over the crowds of participants.

He and some classmates jumped on a bus and rode eight hours to be there for the last five miles of the march.

“It was exhilarating but frightening,” he recalled. “That was the most scared I’ve ever been in my life, and I’ve been where rioting broke out.”

At the end of the journey, surrounded by the National Guard, marchers gathered on the courthouse steps. As preliminary speakers addressed the crowd, the Guard members made lots of noise, but when King stepped up, “it got eerily quiet,” Short said. “Those Guard members didn’t like what he was saying, but he still had them captivated.”

Years later, as chaplain on campus, Short would help found the Peace Studies program and teach conflict resolution at Chapman. He also co-founded the Orange County Interfaith Peace Ministry.

Throughout his ministerial life, he repeatedly has been drawn back to his collegiate moments with Dr. King as touchstones for his own actions on issues of equality and social justice.

“It may have been 50 years ago, but it was a pivotal moment for me, and it remains so,” Short said. “It’s a moment that made me very proud to be a Chapman student.”

Add comment