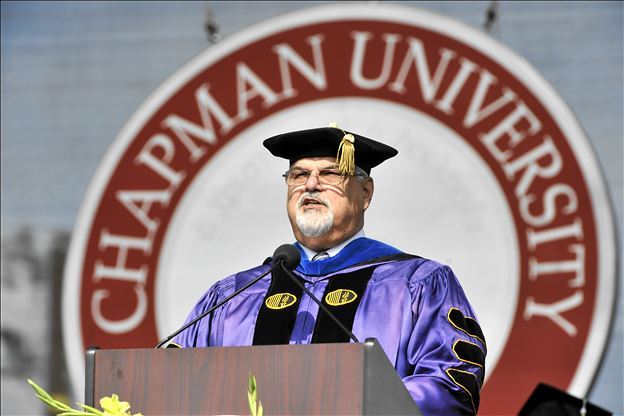

For 13 years as dean of the College of Educational Studies, Don Cardinal, Ph.D., has helped build programs and assemble a distinguished faculty aimed at bringing out the best in future teachers and the students they’ll eventually serve.

Chancellor Daniele Struppa

called Cardinal “a truly special leader in the history of Chapman University.”

Now Cardinal is stepping down to return to the classroom. But he’s hardly finished. A conversation with the outgoing dean reveals that he still has important work to do.

You’ve mentioned that one of the things you’re looking forward to is a return to teaching. When did you first realize you wanted to be a teacher?

I was not a great student in K-12, actually, very poor. High school was a blur and according to records, I had a very low, barely passing GPA and was put in the low-achievers classes. Seriously. One English class had only eight students or so. Pretty much the bad boys. They wouldn’t even let the teacher work with them. That teacher asked me if I would work with the others so they understood the assignment. He gave me a hall pass if I did. At the end of the year he told me I should consider being a teacher. That stuck with me.

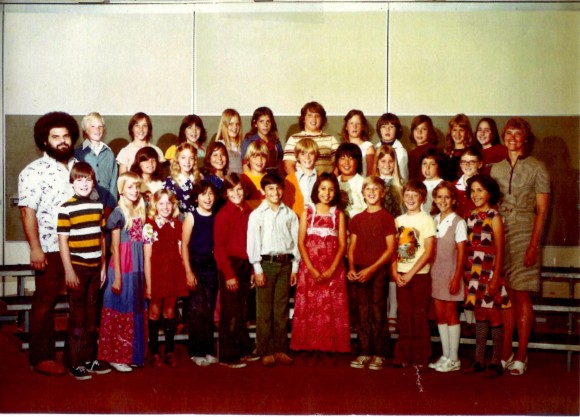

Dean Don Cardinal, Ph.D., in his student teacher days, circa 1976.

Community college was a mess, though, and I was asked to leave in my second semester. (My father passed away just before my senior year in high school.) I came back two years later, much more serious and began to do good work. I was focused. In my final semester before getting my bachelor’s degree in business finance, my then-girlfriend was in student teaching in special education. I visited her class. Shortly thereafter was my first thought of being a teacher.

“Teaching is really the same in all areas. One’s job is to create learning environments, not to transmit knowledge.”

I moved my focus to special education, received several teaching credentials and a master’s degree in special education. I’ve been teaching continuously since 1974 or so, from kindergarten to working in a state hospital to Ph.D. classes. Teaching is really the same in all areas. One’s job is to create learning environments, not to transmit knowledge. People confuse this too often. Leadership is the same I think. Hire great people, clear obstacles and provide the resources needed for faculty to do what they are hired to do. I suppose keeping people focused on shared goals and vision is critical as well. Not just in higher education, but in all areas of teaching.

What sparked your interest in disability studies and research?

I learned how to investigate problems and find solutions in business. Then in special education the quest to solve wicked problems continued. For example, if someone cannot read by age 16, how do you teach them the beauty of the written word or how to fill out a job application? These are all forms of research really, developing hypotheses and testing potential solutions.

With that backdrop, I began to notice that disability seemed more a product of how people were treated than the human characteristics themselves. I began to include within my problem-solving challenges, the systems surrounding those with disabilities; rules, regulations, others’ perceptions, the environment, unchallenged beliefs, social context, etc. I came to understand that “disability” seemed as much created by society as it is inherent to the person with the label. So, obviously, changing the environment around disability could have a major freeing effect on those with the labels. Overly simplified, but this is how disability studies came into play. Looking at disability as a socially constructed phenomena became my focus.

So I entered a Ph.D. program at Claremont to learn more about how best to share these thoughts with the professional community. My work then became one of research in the formal sense. Right after this, I came to Chapman. About five years later, I began to be involved in a national/international controversy in autism that persists today.

What have you learned as an administrator that will be valuable to you as you return to the classroom?

“I plan to also resume my fight of the phobia around math. It is an irrational stance, not a human condition. I want to eradicate it!”

I don’t see the processes as very different. The tasks are, but the idea that my job is to create an environment where students want to learn, is the same as being dean.

Since my teaching focus is research methods and statistics, and that will likely continue, I am eager to pick up on helping others see the value of quantitative logic and how it can assist other ways of knowing in decision-making. I am even more convinced now that many people fear numbers because they only see the work needed to use them correctly and effectively. They do not fully embrace the beauty of math and the insights it can offer. The numbers/symbols used in math, especially statistics, often cloud their conceptual nature. Numbers are often seen and criticized for being reductionist, only parts of the whole, rather than a tool to understanding the world. I suggest that this is due to the miss-use of, and possibly a misunderstanding of, the concepts of quantitative analysis. I plan to also resume my fight of the phobia around math. It is an irrational stance, not a human condition. I want to eradicate it!

If you could give one piece of leadership advice, what would it be?

Hmm. I don’t think so. Advice is a tricky thing in that it often assumes the giver is fully aware of how the advice will be interpreted and of the environment in which it will be used.

I use “Cardinalisms of Leadership” for talks in leadership classes. There are 16 Cardinalisms! But I think my favorite is this: There are no throwaway people. Too often we see issues in organizations as the fault of one person or a few people. So we tend to wish them into the “cornfields.” My experience is that once they are gone, someone else, or some group, will assume that negative role. It is the deeper organizational structure that often needs the intervention. Else, the pattern will simply repeat with the next hire. Nurturing the deep structure within organizations is what good leaders do.

“There are no throwaway people, just people who are stuck.”

Believing that everyone has a role and something to give, and that it is leadership’s responsibility to find the right fit for the person, makes the cornfields a last resort and it makes finding people’s strengths, and ways to use those strengths in the organization, the first option. Doing this regularly creates a culture where people want to reinvent themselves, they do not fear change because they know the organization will help them find a place in the change. There are no throwaway people, just people who are stuck.

Add comment