This story appeared in the spring 2014 issue of Chapman Magazine.

If you have ever taken an aptitude test, been prodded by a physical therapist to exercise while still aching from surgery, looked skeptically at the government’s justification for foreign involvement or been influenced by propaganda marketing, that was World War I talking, even after all these years.

In that moment 100 years ago when a Serbian nationalist assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand on a Sarajevo street, a boom was triggered that still resonates in American politics, education, health care, foreign policy and culture. And we’re not just talking about the affection for BBC dramas — we’re looking at you, Downton Abbey.

Surprised? You’re not alone. Professor Jennifer Keene, Ph. D., knows that most Americans tend to think that World War I didn’t much affect, involve or change the United States.

Granted, the U.S. entered the war late. It sustained far fewer losses than its allies in the horrific trench battles that came to characterize the war that claimed the lives of some 10 million combatants. And to echo a lyric from a patriotic tune of the era, “over there” truly was a long way away.

But as the world marks the centennial of the war’s beginning, no one should discount its imprint on America or the shadow it casts here, says Keene, an internationally recognized scholar of the war.

“Nobody thinks that World War I is important for the United States. That’s my big soap box speech,” Keene says. “Why is World War I important for America and how did it transform the world and the United States?”

The answers are everywhere. Most obvious are the continual struggles in the Middle East and the powder keg of Eastern Europe, where religious and ethnic groups still strain against borders drawn up by the victors in an effort to render the old Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian empires powerless.

“That is the first and most significant outcome, and we still see the legacies of that. The way the Middle East was created, the way the Balkans were created, the way that entirely new states were created — we’re haunted by it today,” says John Hall, Ph.D., a law professor, historian and international law scholar at Chapman’s Dale E. Fowler School of Law.

President Woodrow Wilson’s ideals that American self- determination should be shared around the world still shape American foreign policy, Keene says.

But there are numerous other connections, too.

Pencils Down, Please

Take our culture’s obsession with standardized testing — some might throw in a vehement “please!” It begins in grade school for all children and reaches a test-prepping frenzy in the junior year of high school for teenagers determined to ace the SAT and ACT. The seeds of that zeal were planted in the pre-war progressive era, but World War I brought it into full flower, says Professor James G. Brown, Ph.D., who teaches educational history in Chapman’s College of Educational Studies.

When the U.S. Army was faced with screening millions of recruits, it turned to the new science of psychological testing to quickly sort out who might be officer material, a drill sergeant or a potato peeler. After the war, American schools likewise were challenged by a flood of enrollment, fed by compulsory education laws and a surge of immigration delayed by the war. The timing was perfect. Educators adapted the new technology of testing and ran with it in what historians call the beginning of the efficiency movement in U.S. schools.

“The people who were behind the testing movement really believed that testing was our way to reach a utopia,” Brown says.

The reality that followed was far from paradise.

“The question becomes, then, should we provide the same curriculum to everybody or a differentiated curriculum? Does a bricklayer need to study Shakespeare? Well, how are we going to do that?” he explains. “That’s where we go back to the testing. It does lead to tracking.”

Tracking was also akin to the “scientific” justification for school segregation. Immigrants, the poor, African Americans and just about any other group that couldn’t identify with most of the tests’ cultural references and readings drawn from middle- and upper-class life were always at a disadvantage, Brown says.

Those blunders, as well as today’s debate over the merits of tests like the SAT and ACT, should remind all test writers: “We have to be careful,” Brown says.

Up and Around

Like the Army and the schools, the medical world had to pick up its game during and after WWI because of the sheer numbers coming its way. For the recovering wounded, physical therapy came to the fore, thanks not so much to physicians but to a contingent of women called reconstruction aides, says Jacklyn H. Brechter, Ph.D., chair of the Department of Physical Therapy in the Crean College of Health and Behavioral Sciences.

Like the Army and the schools, the medical world had to pick up its game during and after WWI because of the sheer numbers coming its way. For the recovering wounded, physical therapy came to the fore, thanks not so much to physicians but to a contingent of women called reconstruction aides, says Jacklyn H. Brechter, Ph.D., chair of the Department of Physical Therapy in the Crean College of Health and Behavioral Sciences.

Taking their cues from Scandinavian countries where exercise and gymnastics were embraced, the women reversed the American medical practice of prescribing extended bed rest, Brechter says.

“We learned that if you don’t move, you die. (The aides) learned the value of getting patients up post-injury. You have to get people moving,” she says.

Although far more refined today, much of the treatment physical therapists provide would be familiar to those reconstruction aides, she says. They were the first to understand the mechanics and benefits of resistance training, contract-and-relax exercises and soft-tissue manipulation to improve mobility.

They even pioneered procedures to desensitize post-amputation limbs for prosthetic devices — an advancement borne out of necessity because of the heavy use of artillery. The practice helped generations of war wounded.

“There were a lot of amputees, but when these people were left in bed to recuperate, the limb would tighten up and become sensitive,” she says. “So they started with gentle pressure and would build, build and build until they could take the pressure of a prosthetic device.”

Lingering Cloud

Mass casualties and the kinds of wounds that kept reconstruction aides busy were inescapable in a conflict the size and length of the war, but intolerance for poison gas weaponry was fierce, creating the spark for international bans of today.

“The use of poison weaponry, the horrific nature of the injuries, was different in kind, not just different in scale. It reverberated in a number of ways,” including a host of international laws banning their use, Hall says. While some regimes have used such weapons since then, more have shelved them, aware that the international response would brand them as pariah states, Hall says.

“When the Syrian regime decided to hand over its poisonous gas munitions, I think this was really very interesting. It’s this notion that the use of poison weaponry is too abhorrent to the world. That’s this lingering memory of the First World War,” he says.

Cynicism on the March

Perhaps the most subtle but ingrained legacy of the war on Americans is something that’s harder to pin down.

“In terms of America, if there was one change that came about from World War I, it was cynicism,” says Chapman historian and author Robert Slayton, Ph.D., who holds the Henry Salvatori Professorship in American Values and Traditions and teaches a course on the history of everyday life in America.

Americans felt betrayed by everything from the propaganda of the era that inflated and manipulated reports of German atrocities on Belgians to the enormous slaughter in what most considered “the stupidest war in history,” Slayton says.

“People generally think that (cynicism) was a product of the Vietnam Era. No, that really is a product of the First World War,” he says.

Selling the War

Much of the distrust can be traced to a World War I phenomenon — the use of government-controlled propaganda. But that’s not to say that when the U.S. first entered the war in 1917, the government’s message wasn’t effective. Posters with powerful visuals were developed and displayed just about everywhere there was foot traffic. The message was obvious, even to those who couldn’t read: The European threat is real, so better to confront it over there rather than wait for it to cross the Atlantic.

There were two main purposes of the posters — to fund the war by encouraging people to buy bonds, and to generate “the fodder of the war — getting men to sign up,” says Gail Griswold, an adjunct art professor at Chapman who teaches the history of graphic design.

And the U.S. wasn’t the only country pumping up nationalistic fervor.

“The closer you get to ground zero in this, the more urgent the posters,” Griswold said. “Germany’s message is extremely hard-edged; they were fighting for their lives. England’s approach was more ‘Save our families.’”

U.S. posters were image driven, with very little text. These posters introduced Americans to Uncle Sam, who pointed a finger and said, “I want you for U.S. Army.” There was also a demonic-looking Hun with blood dripping from his bayonet and a teeth-bearing gorilla that wielded the club of German kultur (culture) in one hand and held a half-naked woman in the other.

“One thing graphic designers knew back then was that they had a tremendous influence over people. That visual contact is everything, and graphic designers were able to grab hold of that,” Griswold said.

As the war wound down, Americans started to question the message they’d been fed. The distrust was compounded as immigration, which had been put on hold by the war, rose again and the 1920 census revealed that for the first time in U.S. history, the majority of the country’s population was urban.

“It’s the first census where we are no longer a country of farmers. … The country gets hysterical,” Slayton says.

That hysteria prompted immigration restrictions and was the final push needed to pass Prohibition, but a wariness of change and government became a lasting part of the national consciousness, Slayton says.

Keene agrees. Whenever news followers question government reports, statistics or motives, they’re echoing questions most citizens didn’t ask until after World War I, she says.

“A lot of people want to link this mistrust to Vietnam, where it also belongs, but it actually goes back to World War I.”

Censorship in the Field

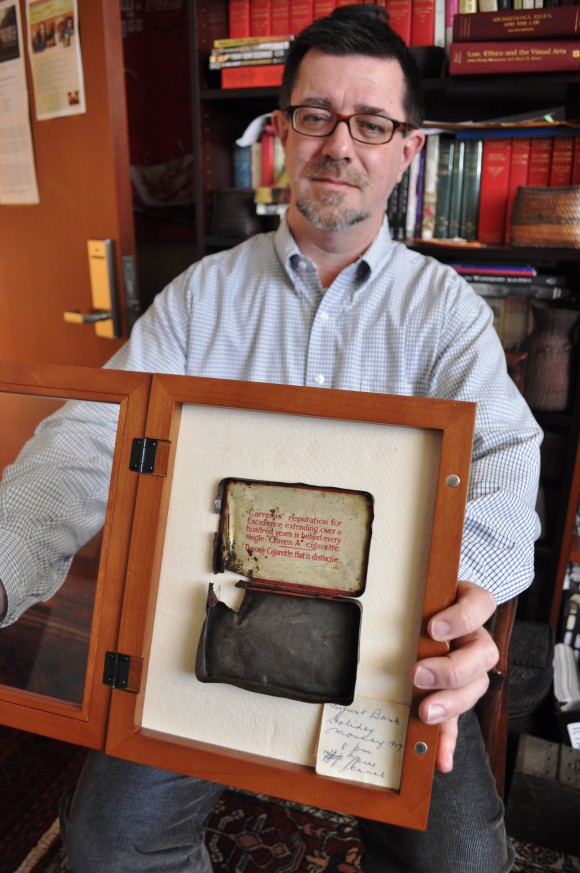

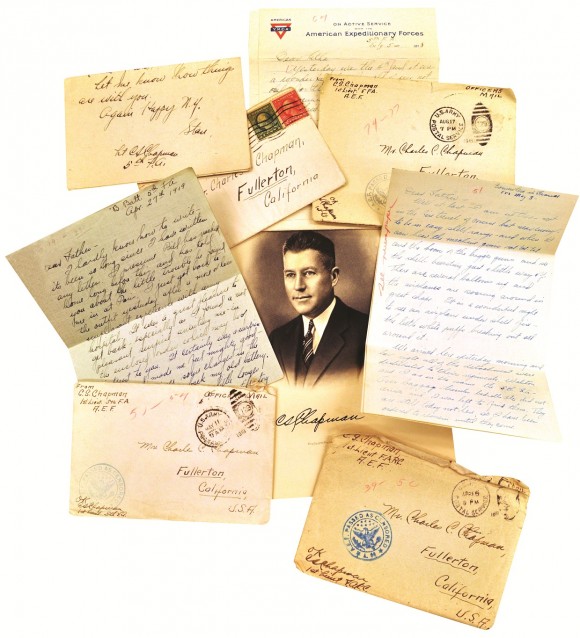

Even during the war, there was a fair amount of mistrust that extended from the trenches right through to Allied headquarters. For the first time, U.S. officers censored their troops’ letters home, because of worries that they would divulge strategic information.

“Civil War soldiers wrote pretty much whatever they wanted,” said historian Andrew Carroll, director of the Center for American War Letters at Chapman University. “In some cases they were very graphic, and they weren’t shy about complaining about their commanders.”

Because the Civil War was fought on home turf, and soldiers of lower rank often didn’t know until the last minute when and where an attack would come, there was little concern about giving away secrets, Carroll said.

“In World War I, there was so much fighting on the Atlantic that it was completely conceivable that letters could fall into the wrong hands,” Keene added. “Plus, there were lots of German Americans back home.”

Officers would simply black out sections deemed inappropriate, Keene said. Of course, there were complications. Because of immigration, letters were being written home in as many as 50 different languages, Carroll noted. The letters also highlighted a widespread problem with literacy. This revelation helped fuel a final post-war push for compulsory education — something for which progressives had long lobbied, Keene said.

At least at the beginning of U.S. involvement in the war, service members who did write letters struck a distinctly American tone, Carroll noted.

“They’re full of optimism,” said Carroll, who oversees the Chapman collection of as many as 100,000 letters, from every war involving U.S. troops. “It was the fresh blood of the Americans that helped win the war, and that fighting spirit really comes across in the letters, although by the end of the war, they do confront the enormity of the suffering they’ve seen.”

A Narrative Deficiency

Finally, what’s behind Americans’ fuzzy vision about the so-called Great War? After all, it preoccupied American novelists like Ernest Hemingway, ramped up the country’s international role and resulted in Veteran’s Day being on Nov. 11, a memorial to the Armistice that ended the blood bath at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month.

Keene suspects that it’s related to that fuzziness: The war was about so many things, it’s hard to attach a narrative that makes sense of all its ambiguity.

“Americans don’t have a natural place for World War I in their national narrative. What role did it have? How did it change us? There’s not a straightforward answer to those questions,” she says. “It’s not ‘It ended slavery,’ ‘It defeated Nazism.’ You don’t have that quick shorthand answer for it. It’s essentially a little bit here, a little bit there, and that makes it an important war.”

Add comment