If silver had a season, this would be it. It’s everywhere, from sterling menorahs and heirloom silverware trotted out for holiday dinners, to shiny gifts in small boxes.

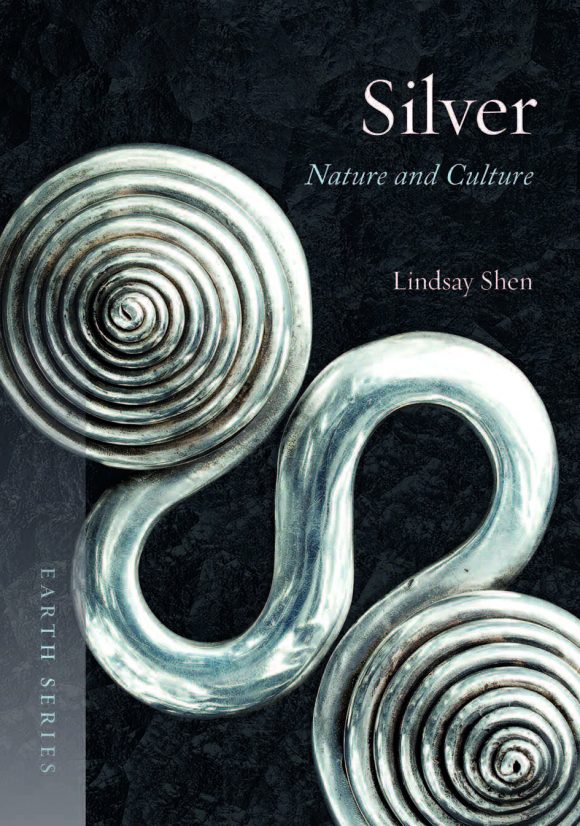

But, in fact, it’s always around us – in our phones, medicines, socks, Olympic medals – yes, even the gold ones – and, especially, our history and culture. Art historian Lindsay Shen, Ph.D., director of Art Collections at Chapman University, explores the long and shiny reach of the lustrous metal in her new book Silver, published by Reaktion Books for its Earth series.

Silver linings

As Shen see it, silver is no second cousin to you-know-what because the properties of the lustrous white metal are uniquely valuable, and its beauty is just as striking.

“If what you need is silver, it doesn’t really matter that gold is the more scarce or precious material. It’s almost like saying water is more precious than air,” she says.

Her interest in the topic evolved over time. She’s worked and taught in museums and universities around the world, noting along the way that silver was a recurring theme in culture, art and history, as well as technology.

“I began to notice that in different cultures silver would pop up with shared meanings,” she says.

That can be attributed in part to the nature of the metal. For generations, artisans worldwide have enjoyed its malleable qualities, while its chemical properties proved essential to the development of photographic film and electronics. But less obvious is the shared view of silver as a source of protection, she says.

Cyrus had a great hunch

And she’s not just talking about those silver stakes that come in handy when vanquishing pesky vampires. In ancient China, parents embroidered small silver mirrors and sieves into children’s clothing to deflect evil. Likewise, early Norwegians affixed silver amulets and brooches to their children to ward off huldrefolk, or trolls. Cyrus the Great is said to have demanded that his water be stored in silver containers to keep it pure.

“There are even pioneer stories about putting a silver coin in your milk to keep it fresh,” she says.

Today scientists understand silver’s antibacterial properties and put it to work in a variety of ways, from cosmetics to antimicrobial coatings for medical devices. It’s a reminder that ancient folks might have had a good hunch or two.

“They understood from experience that somehow silver could keep things from being tainted,” she says.

Silver bidet anyone?

Other highlights of her book are chapters titled “Silver Transformed” and “Status Symbols,” chock full of photos and stories of silver turned extravagant and useful, from a bidet to a Paul Revere teapot. In another section she describes the landscapes where silver has been found through the eons, including briefly in Orange County’s Silverado Canyon, just a few miles from Chapman.

Among her own silver collection, Shen prizes her great-grandmother’s Edwardian-era belt, an artisan bracelet from China and a keepsake napkin ring given to her as a baby.

“I come from Britain, where we’ve long been interested in status symbols. As a baby, you’re often given a silver napkin ring,” she says with a laugh and a shrug. “Why a baby needs a napkin ring, I don’t know. But it is a very traditional present for babies.”

But like silver itself, it will always be something to be prized and certainly won’t hurt to keep at hand.

Display image at top/Her great-grandmother’s silver belt is among Shen’s prized silver pieces. Photo/Amanda Galemmo ’20

Add comment