A Chapman professor and team of student researchers are exposing the questionable practices of some supplement companies that could put consumers at risk.

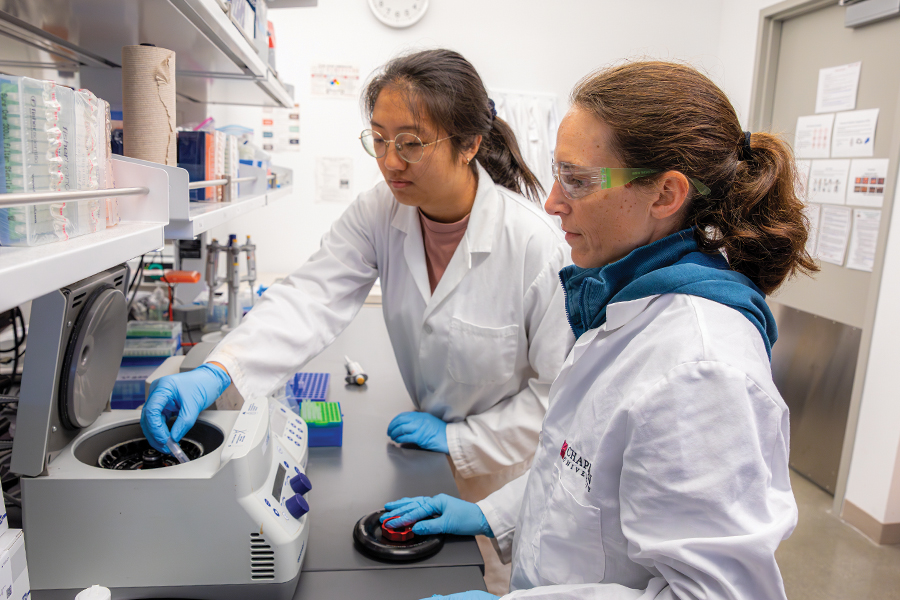

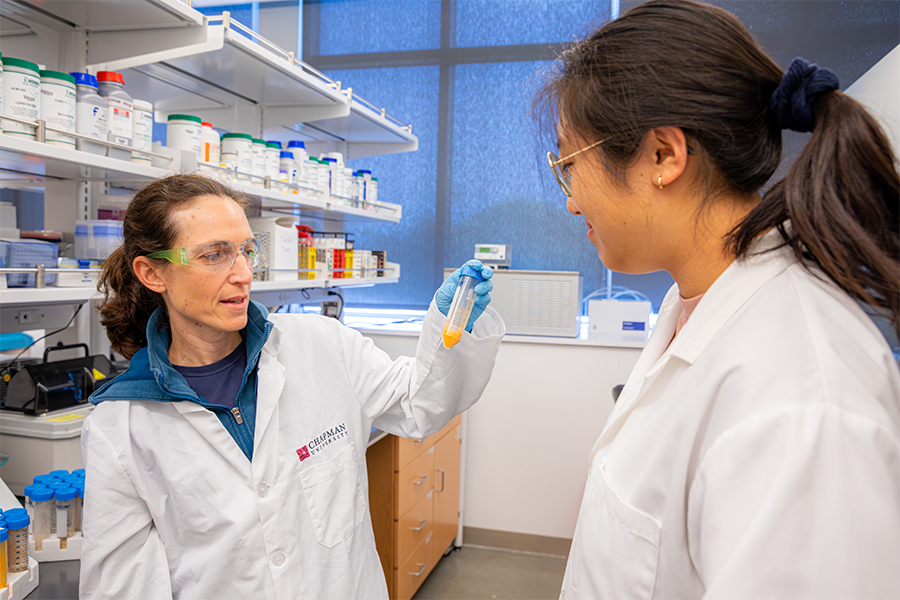

Two studies conducted by Professor Rosalee Hellberg and students Calin Harris, Diane Kim, Miranda Miranda and Chevon Jordan, reveal that some supplement companies may mislead customers with unproven health claims and undeclared ingredients. The researchers specifically focused on supplements that have been associated with the purported treatment or prevention of COVID-19 and other respiratory illnesses.

During the pandemic, the use of dietary supplements skyrocketed throughout the world. Individual use of supplements increased by about 35% in the United States during this period. The industry had already been growing significantly before the pandemic, with a rise in herbal supplement sales from $9.6 billion to $11.3 billion in 2020, according to the Chapman researchers.

The increase could be concerning given the limited regulatory oversight of the supplement industry. While supplements may be useful in improving immune function, particularly in people with vitamin deficiencies, supplements may contain undisclosed ingredients or lack a sufficient amount of the stated substances. Although supplements are regulated by the Food and Drug Administration, they are under a different set of regulations than those covering other foods and drugs. Supplement companies do not need to get approval from the FDA prior to placing supplements on shelves, according to the researchers.

“There was a big spike in purchase and use of these types of supplements during the pandemic,” Hellberg said. “Whenever there’s an increase in demand, there’s also an increased chance for fraud to occur.”

Consumer Risks

For the most recent study published by the researchers, the Chapman team collected 54 supplements containing Ayurvedic herbs, which refers to alternative medicine originating from India. They specifically chose herbs that had been used for the purported treatment of COVID-19. These included ashwagandha, cinnamon, ginger, turmeric, tulsi, vacha, amla, guduchi and tribulus.

The products were purchased online and from local retailers in Orange and Los Angeles counties. Ayurvedic supplements have been rising in popularity in the last few years. But their efficacy remains in question. Recently, the Supreme Court of India temporarily banned one of the country’s largest manufacturers of Ayurvedic herbs from advertising some of its products, with one judge claiming that “the entire country has been taken for a ride.”

The Chapman researchers analyzed whether they could use DNA barcoding techniques to identify plant species in supplements to help determine the authenticity of the products. DNA barcoding is a method that allows scientists to use a short section of a DNA sequence to identify the species of an organism.

The results of the study revealed several concerns indicating a need for increased scrutiny of these products. In 60% of the products, the researchers did not detect the expected ingredient. However, Hellberg did not explicitly pin these results on fraud. The DNA barcoding method, because it’s being utilized in a novel way, may have a limited ability to detect degraded DNA. Therefore, a negative result does not necessarily prove the absence of the species in the product.

The researchers also uncovered 19 products with undeclared plant species. Rice and a few other materials were used as common fillers. They also identified other Ayurvedic herbs that were not listed on labels.

“So these could be used in a fraudulent manner,” Hellberg said. “Instead of having 100% of the declared species on the label, some manufacturers might mix in filler because it’s cheaper. There’s also a possibility for cross contamination. When these herbs are harvested, plants growing in the same area could get mixed in. During processing there’s also a chance for contamination from other supplement products manufactured in the same facility.”

Another limitation of the DNA barcoding method is it doesn’t reveal the quantity of the detected species of ingredients. Additional research would be necessary to verify the amount of each, Hellberg said.

With undeclared species and ingredients in supplements, consumers could ingest substances that cause allergic reactions and other health risks. However, it isn’t clear from the study how high the risk would be because the researchers were not able to detect the amount of each ingredient.

“If the ingredients were present at a higher amount, that is where the concerns can arise,” Hellberg said. “Also, any time you’re detecting things that aren’t on the label, that can indicate some quality control issues. That could also suggest that there are other health risks going on or maybe things aren’t being handled properly.”

Hellberg noted that as she conducts further research on supplements, she would like to incorporate chemical-based research methods in addition to DNA detection to identify the amount of each ingredient in a supplement.

Questionable Business Practices

Researching supplements is an ongoing project for Hellberg. She’s currently conducting a similar study with students Diane Kim, Adriana Ten Cate, and Donna Miranda-Romo investigating ginseng products with DNA barcoding and other targeted DNA-based methods. Last year, Hellberg and her team of student researchers published another paper analyzing the validity of claims made by supplement companies on the labels of their products.

Those findings also brought to light questionable labeling practices, with 61% of herbal supplements that were examined having violated some form of government requirement. This included missing disclaimers and mailing addresses or phone numbers, which limits consumers’ abilities to report adverse effects.

The researchers also analyzed the online profile of supplements and compared the claims made online to those found on labels. Researchers found many more questionable health claims online.

“Some of the claims were clearly not legal,” Hellberg said. “It’s very concerning because consumers are going to read that and possibly think it’s true when these claims haven’t been clinically proven.”

More than a third of the supplements featured an online claim that either explicitly or implicitly indicated that the products could be used to prevent, treat, or cure diseases. The researchers noted that this is a “major public health concern.”

“…Many consumers are not likely to understand the regulatory differences between dietary supplements and drugs,” the researchers said. “This misunderstanding may present serious risks to consumers that delay seeking proper medical attention for the treatment of life-threatening diseases.”