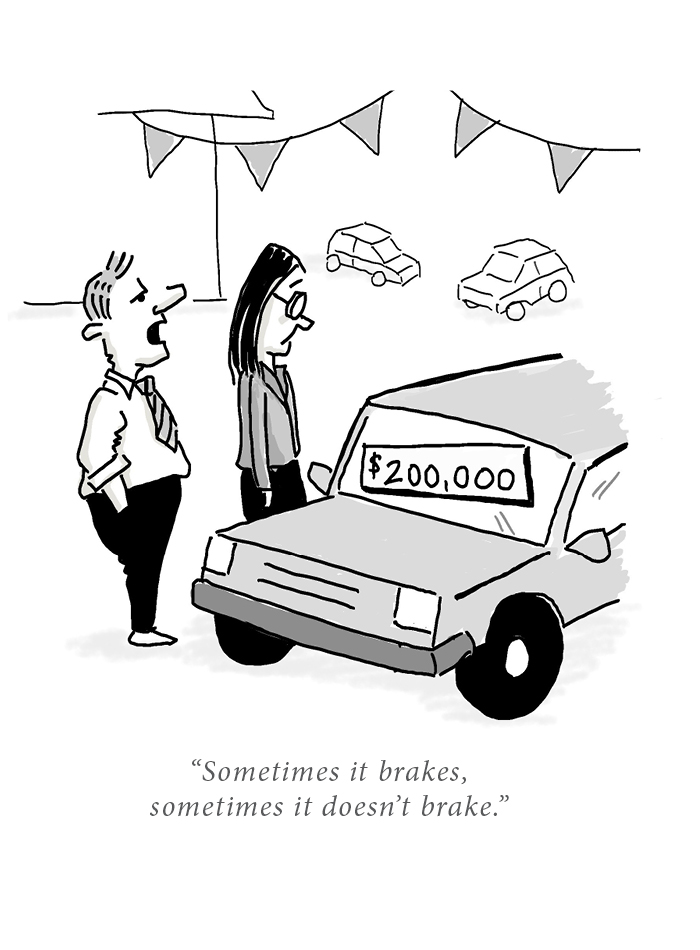

When shopping for a car, a buyer doesn’t spend over $100,000 on a vehicle that hasn’t been rigorously tested.

Yet, the Food and Drug Administration would have buyers spend exorbitant amounts on many untested new drugs, according to a Chapman University professor.

“What is the fuel consumption? ‘We didn’t test that.’ Then tell me it brakes well. ‘We only tested 10 cars – sometimes it brakes, sometimes it doesn’t brake,’ says Enrique Seoane-Vazquez, a professor at Chapman’s School of Pharmacy. “What if you charged $200,000 for this car? Someone will say, ‘No, I don’t want this car,’”

“But with pharmaceuticals, the FDA allows these companies to enter the market without evidence that the drugs actually work,” he says.

The United States is infamous for high drug prices, and many Americans turn abroad for affordable medications. But many newer FDA-approved medications may not have been green-lighted overseas, according to a study published in JAMA Internal Medicine by Seoane-Vazquez, former School of Pharmacy fellow Catherine Pham and two co-authors from Kaiser Permanente.

Of 206 new drug approvals from 2017 to 2020 in the U.S., 47 – a fifth of the total studied – were not recommended for use or reimbursement in other countries because of issues like “uncertain clinical benefit” or “unacceptably high price.” The median cost in the U.S. for these drugs was $115,281 per person per year, according to the study.

Drugs in the JAMA study ranged from antibiotic ozenoxacin – sold as Ozanex to treat impetigo at a mere $312 for five days – to cerliponase alfa, which targets a rare pediatric neurological disease with a price tag of about $755,900 per year. The former wasn’t recommended for reimbursement in Canada, deemed “unlikely to justify the price premium proposed. Cerliponase alfa wasn’t recommended for reimbursement in Australia due to “uncertainty regarding survival benefit and an unacceptably high proposed price,” Seoane-Vazquez and his co-authors write.

“Drug expenditures in the U.S. are higher than in any other country and are projected to continue increasing, so U.S. health systems may benefit from evaluating international regulatory and reimbursement decision-making of new drugs,” according to the study.

They analyzed recommendations issued by agencies in Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom for new drugs approved by the FDA from 2017 to 2020.

Twenty of the 206 new drugs – which were examined by active ingredient – were for cancer treatment, and 36 were approved by the FDA through the 1983 Orphan Drug Act. Many were fast tracked for approval. Thirty drugs on the market that have been approved by the FDA for over two years remain unauthorized by the agencies abroad.

Seoane-Vazquez and his co-authors believe this is the first such study. They conclude that reviewing refusals by international regulators “can support safe and cost-effective clinical decision-making by US health systems and payers.”

Seoane-Vazquez, who is also part of Chapman’s Economic Science Institute, says that new drugs should be analyzed for adding value, or improvement in patients’ outcomes.

“We need to bring together the value, the safety and efficacy, and then combine those with the cost to ensure that the drugs are available and affordable for patients,” he says.

Instead of reference pricing – which places a limit on an insurer’s or employer’s contribution to a health care service – the U.S. could move toward a value-based reimbursement system similar to health systems abroad, the authors recommend.

“With annual U.S. prescription drug spending expected to increase, reimbursement criteria such as comparative clinical benefit and cost-effectiveness may be considered to address issues of health-care affordability and access,” Seoane-Vazquez and his co-authors write.

Many health care providers he works with won’t recommend a drug whose value hasn’t been proven through enough clinical trials, he says.

“I work with oncologists, and one of my colleagues tells me what he tells the patient: ‘You can have this new therapy that will probably extend your life a few more days, but you will be in the hospital in intensive care. Or you can just decide to have palliative care, be at home and have a better quality of life.’”

These are tough decisions, and often the person making them doesn’t have enough information about a new drug – often because it was fast tracked to the market. This can create false expectations, he says.

“Sometimes we are desperate. We want to have an alternative,” he says.

He tells his pharmacy students that just because a drug is FDA approved doesn’t mean it’s appropriate for a patient. Like buying a car, why pay a premium?

“We need information about the safety and efficacy of a new drug. If we know that it works, we can decide to pay more for improved patients’ health,” he says.