At some point all kids go through a dinosaur phase. Ben Rotenberg ’23 pretty much started his at birth.

Family photos show him sleeping in a crib packed with dinosaur toys; in other snapshots, he’s wearing a dinosaur onesie or has his face halfway buried in a dinosaur birthday cake.

Alas, Rotenberg’s longings for a life full of prehistoric adventures didn’t survive his childhood.

Or did they?

“You get to a certain age and the idea of studying and actually working with dinosaurs seems so unattainable,” said Rotenberg, a senior at Chapman University. “But now, here I am working with this fossil discovery, and I’m having this incredible life-changing experience that I want to continue when this project is finished. I want this to be my life.”

Far surpassing “Jurassic Park” dreams, Rotenberg and fellow students Amalie Seyffert ’23 and Molly Steavpack ’24 are fulfilling some Late Cretaceous aspirations. In a first-floor lab at Hashinger Science Center, they’re bringing to light the fossilized remains of a Gryposaurus, a 40-foot-long genus of duckbill that roamed the then-swampy Badlands of Montana 78 million years ago.

None of the students started their Chapman Experience expecting to dig into paleontology – Rotenberg is studying screen acting and Seyffert documentary filmmaking, while Steavpack is majoring in English literature. But they’ve all found that Chapman is a great place to explore new fields, develop new communities and take up new challenges.

“It’s like doubling down on science learning for someone like me, who’s never felt drawn to the more typical forms of science education,” said Seyffert, an Honors Program student who’s working on a documentary about the project. “To have this hands-on experience with paleontology and the science discipline every day is immensely fulfilling.”

Legendary Paleontologist Leads Field Work in Montana

The work started last summer, when the three were among a larger student contingent that traveled to Montana to join in field research led by Professor Jack Horner. Since 2016, the legendary paleontologist has been a presidential fellow at Chapman, where he teaches an Honors course that takes students inside his breakthrough thinking.

Horner shook up scientific theory when he became the first scientist to prove that dinosaurs cared for their young. Later, he took on the role of paleontology consultant for the “Jurassic Park” film franchise.

During several weeks of fossil prospecting last June, the team revisited a discovery that Chapman student Sarah Wallace ’22 had made the previous summer. That’s when Seyffert and fellow film student Flo Singer ’22 began work on their documentary, which is still in progress.

Ultimately, after lots of strategizing and teamwork, the Gryposaurus fossil was freed from a hillside and wrapped in a 4,000-pound jacket of plaster for transportation to Orange County so excavation can continue.

Thanks to a generous donor and the tutelage of Horner, Rotenberg, Seyffert and Steavpack have been applying their new skills throughout the fall and winter in a lab set up just for the project. Working around their class schedules, they’re peeling away layers to reveal more and more of the Gryposaurus skeleton each day, as they also share the experience with students and visitors via social media, blog posts and other means.

Excavation Work Invites Conversations and Sparks Questions

When they’re working, they swing the lab’s double doors wide open and post a sign of welcome to invite visitors inside so the students can share their journey.

The specimen has told them a lot already, including about the environment the Gryposaurus called home. But the participants and their mentor are left with more questions than answers, which fuels their interest to learn more.

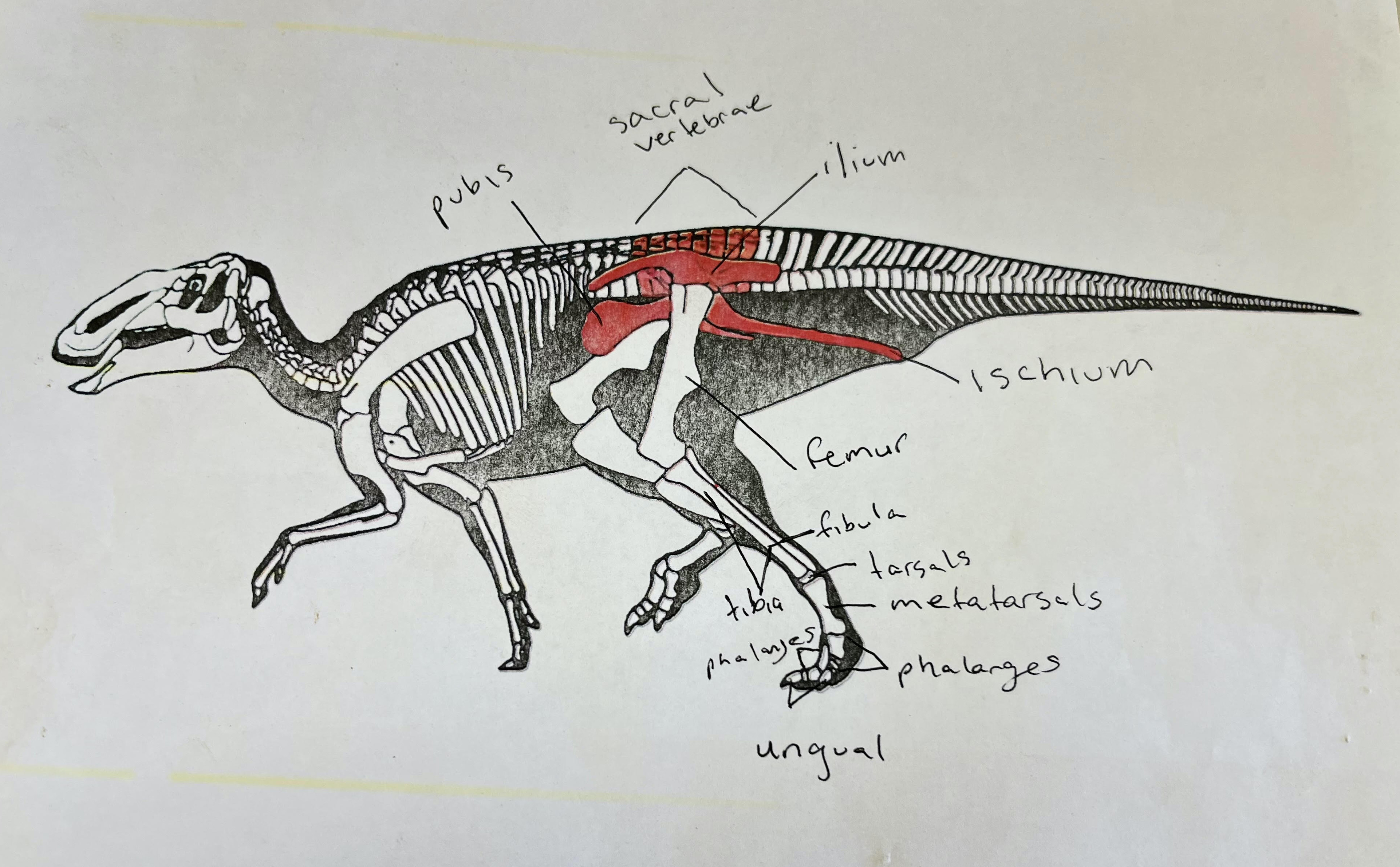

“This is an unusual specimen – the most puzzling I’ve seen,” Horner said. “We have the whole pelvis, short one bone. And that one bone is the opposite of the pubis, that big flat bone,” he added, pointing to the fossil in front of him. “Usually when you find this part articulated, you find the whole skeleton together. It’s just weird that the tail is missing.”

Finding more pieces to the puzzle is why Horner and the students will return to the field in June. They plan to widen the search and include more participants in a project that Horner says will turn into a research paper, with Chapman students among the co-authors.

Rotenberg isn’t the only one for whom this is a life-changing experience.

“Being involved in this project has reinforced my appreciation for science as a whole, and for what we can accomplish as a community,” Steavpack said. “We’re working to better our knowledge while also honoring something that doesn’t exist anymore, and that’s special to me. There’s no way to communicate with these animals that lived for hundreds of millions of years, but there is a way to connect with and preserve them. We’re doing what we can while we are here.”

Project Has Potential to Inspire Future Generations

Though the fossil excavation is a here-and-now experience, the impact of the find will endure.

Once all that’s in the plaster jacket is uncovered – probably by the end of the spring semester – the bones will go back on the road. Their ultimate destination is the Burke Museum of Natural history and Culture at the University of Washington in Seattle.

But before the fossils depart, the hope is that they can be scanned and turned into 3D-printed replicas at Chapman’s Fowler School of Engineering. That way the fossil find can continue to captivate and educate Chapman students for generations to come.

“One of the things I try to get across in my classes is that there are great rewards in putting down your phone and taking a good look at the natural world,” Horner said. “You can always go to Instagram and look at a picture of a dinosaur bone, but to see one in person is mind-boggling, right?”

Sure, but the fascination wanes after more than six decades in the field, yes?

“I’m as excited to find a dinosaur fossil now as I was as a little kid,” Horner said. “I mean, look at this – don’t you think this is a pretty cool thing?”

Rotenberg didn’t need to answer. He just smiled as he used a dental pick and a paint brush to meticulously remove Montana soil from 78 million years of history.

As he considers his own next steps, possibly including study toward a career in museum collection management or fossil preparation, Rotenberg is enjoying every moment of his chance to live out a lifelong dream.

“In my entire life, I never thought I would have an opportunity like this,” he says. “The fascination that began when I was a baby is now opening new avenues. That’s incredibly exciting.”