An ivory tower is no place for a scientist when a storm of misinformation rages.

Climb down and share what you know in a way that recognizes biases, teaches environmental literacy and invites trusted messengers to help drive the conversation. So says Richelle Tanner, Ph.D., an assistant professor of Environmental Science and Policy at Chapman University who is recognized nationally for her skills as a science communicator.

Tanner wants scientists, K-12 teachers and other science professionals to know that by using well-researched communication techniques, they can empower everyday citizens to help solve complex 21st-century problems like climate change.

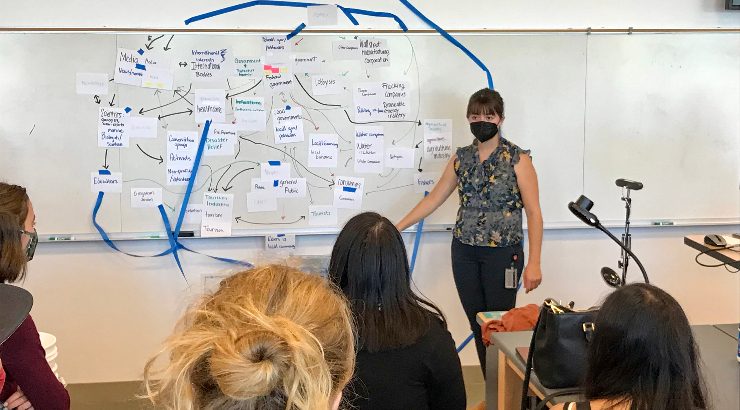

“Traditionally, scientists are up in that ivory tower, where they’re taught to approach [issues] with the perspective of an expert. But that’s not an effective way to communicate,” says Tanner, a biologist who researches coastal nearshore communities. She also teaches an interdisciplinary course at Chapman called “Environmental Advocacy Through Story.”

In addition to her role as a professor at Chapman, she serves as science director for the National Network for Ocean and Climate Change interpretation (NNOCCI), which provides training developed through social science research and promotes effective ways to engage audiences on issues of climate and ocean change.

“You don’t tell people that they have to listen to you because you’re better at this than they are,” Tanner says. “With the younger generation of scientists, we realize this is not a useful or equitable way to do the work.”

Tanner offers these tips to help scientists communicate effectively about climate change and other environmental issues.

1. Empower Trusted Messengers

Scientists are not always the best sources of information, even on issues of science, Tanner says.

“I’m not the right messenger for most of the population,” she acknowledges. “To have the greatest effect, I have to teach people who are trusted.”

Students — and young people in general — make great messengers, she notes. “They come from all sorts of backgrounds, so they can reach diverse audiences. Studies show that they have a lot of influence over their parents and their communities. We just need to give them the tools to advocate for themselves.”

2. Meet People on Common Ground

Find traits or experiences you share with your audience.

Tanner’s research on environmental communication points to two universal values — protecting the environment for future generations and responsible management of resources.

“No matter the stakeholder group, these values hold together,” Tanner says. “An appeal to shared values needs to be up front, so people have an inherent buy-in.”

3. Don’t Skip Foundational Steps in Building Your Case

In addition to values, a shared knowledge base matters. Don’t assume that terms like “climate change” and “global warming” are universally understood.

“Often I don’t even say ‘climate change’ because it can be its own can of worms,” Tanner says. “To explain, I say, ‘When we burn fossil fuels like coal, oil and natural gas, we contribute to a heat-trapping blanket around our earth, which warms our planet.’ Making sure we have a common understanding can help get us past biases and assumptions and guide us toward productive thinking.”

4. Focus on Community-Wide Solutions That Match the Scale of the Problem

Don’t present people with a problem without helping them to see themselves in the solution, she says. But the solution has to match the scale of the problem.

“We do our audience a disservice by pretending that individual steps like turning off lights is enough,” Tanner says.

Community-level solutions might be opting for clean energy in your electric utility’s portfolio or attending a local town hall to advocate for policies that add solar panels and EV charging stations.

“Normalizing the conversation makes it socially OK to pursue large-scale solutions,” she adds.

5. Give Yourself Permission to Share the Burden

It’s not scientists’ responsibility to carry the conversation to everyone they meet, Tanner says.

“Don’t think you have to solve things by yourself,” she adds. “Know that a community is fighting with you.”

Learn More

Richelle Tanner, Ph.D., is a member of the SEACR Lab (Socio-Ecological Adaptation and Climate Resilience), a research group in Chapman’s Environmental Science and Policy Program committed to science in service of communities. Learn more about opportunities for training in effective science communication.