On February 15, 2008, I received an e-mail out of the blue from John Benitz, one of Chapman University’s esteemed theatre professors, after he had read an article I‘d written for National Geographic about an initiative I had launched, called “The Legacy Project,” to seek out and preserve war letters from every American conflict. My purpose was not only to save history, but to honor and remember our nation’s troops, veterans and their loved ones, as expressed in their own words—the letters, and now emails, they have exchanged with one another.

Professor Benitz (from here on, just John, since he has become a close friend) learned of my travels to all 50 U.S. states and to almost 40 countries, including Iraq and Afghanistan, to search for war-related correspondences, and he had also read my two anthologies “War Letters” and “Behind the Lines.” In his first e-mail to me, John suggested that certain letters in the books, if woven together with stories from my travels, could be the basis of a play. Would I be interested, he asked, in workshopping a script with his acting students? I told John that I had been thinking about doing a play as well, so I replied that I was definitely willing to move forward.

My First Visit to Chapman

While I had certainly heard of Chapman, I had never been to the campus, and after I arrived, I was quickly impressed by the energy and pride (“Go Panthers!) of the Chapman community. And once I started working with John and his students, I was very moved by how respectful these young men and women were towards the material (the letters) and the troops and veterans who had written them.

Over time, I was introduced to senior members of the administration, primarily (then) President Jim Doti and Daniele Struppa, who was the chancellor, as well as Sheryl Bourgeois, and they all seemed to instantly “get” the mission of the Legacy Project. I also had the opportunity, thanks to professors Jan Osborn, William Cuniford, Marilyn Harran, Jennifer Keene, Jana Remy, and Robert Slayton, to talk about the Legacy Project with their students and show them some of the best letters from my collection. I was very grateful for how welcoming and gracious all of the faculty members were.

By this time, in around 2010, Americans had shared with me an estimated 100,000 letters from every conflict in U.S. history – from handwritten missives penned during the American Revolution to emails sent from Iraq and Afghanistan. The physical collection was so large that I had to rent out a second apartment in my building, back in Washington, D.C., just to “house” the letters.

Many prominent organizations, institutions and universities had contacted me about donating the collection to them, but, for whatever reason, I was afraid that once they accepted this unique collection, they would just lock it all up in storage room and no one would ever see them. But I did realize that I needed get these letters someplace where they would be professionally archived, and with the understanding that whichever institution received them would be pro-active about growing the collection.

Choosing Chapman

For all of the reasons I’ve mentioned above about, essentially, falling in love with the Chapman community, I informally hinted to President Doti and Chancellor Struppa that I was considering Chapman as the recipient of the entire collection, and I would donate it free of charge and without the hassle and cost to Chapman of an appraisal, which most donors of physical materials (i.e., not actual funding) request for tax purposes. They both responded very positively, and in a relatively short period of time, it was agreed that the Legacy Project correspondences would be given to Chapman University, and we would actually create an entire “center” based on the collection. Since the name “The Legacy Project” wasn’t self-explanatory, we decided to re-name it: The Center for American War Letters.

The collection was so massive that it required a moving truck to transport everything from Washington, D.C. to California. I was so terrified at the prospect of getting into an accident that would destroy the letters that I hired a professional company, “Two Marines and a Van,” to drive the letters from the East to the West coasts. (I mean, who better to entrust getting 100,000 war letters from one side of the country to the other than two young veterans?)

Growing by Leaps and Bounds; The Play, The Film, The Podcast and the Entirely Virtual Museum

Just as I had hoped, and thanks especially to the leadership of now President Struppa and the help and support of Dean Kevin Ross and Julie Artman (along with all of the hardworking archivists in Leatherby Libraries,) we are close to doubling the size of the collection, with new donations of letters coming in almost every day.

John Benitz and I, indeed, were able to create a play based on my travels and many of our best correspondences, titled “If All the Sky Were Paper” (the line comes from a letter in the script), which has toured the country. We even had the honor of performing it at the Kennedy Center, which, for a native Washingtonian like myself, is comparable to seeing one’s play on Broadway. We’re only on hiatus now because of the pandemic, but it will be back in theatres soon. Also, thanks to John, we have an incredible number of Oscar-nominated or winning actors who have performed in the play, including Laura Dern, Annette Bening, Common, Gary Cole, Ed Asner and Mary Steenburgen.

John Benitz and I are now working as well on a documentary – tentatively titled “War Unfolding: In Search of the Greatest Letters Ever Written” – based on the overall effort, and we’re thrilled that Chapman alum Bryce Cyrier, who recently joined Sypher Films, is working with us. Bryce is not only one of the most thougtful and considerate people I’ve ever met, he’s also one of the most brilliant and creative.

Because of my friendship with an award-winning producer and writer, Celia Straus, I’m now working on a podcast, called “Behind the Lines,” with the journalist Barbara Harrison, who has won nineteen Emmys. We’ve done four episodes so far, but we hope to do many more if we can secure the funding. Everyone has a podcast now, and I’m so grateful to Celia and Barbara for investing both their time and resources to get this project off the ground.

And finally, I am very happy to announce that we have begun the “construction” on the entirely virtual Museum of American War Letters. Thanks to an unsolicited grant (i.e., they came to us!) from the National Endowment for the Humanities, we have the funding to create this pioneering museum. Working with a sensational company called Treasured, we opened our inaugural wing, about the Vietnam War, on March 29, 2021. (We chose that war because we knew we could meet that March 29 deadline, and that day is now, officially, National Vietnam War Veterans Day.) We were fortunate to be featured on the front page of The New York Times’ Arts section, and then, later that day, CBS Evening News ran a wonderful story on the museum as well.

The Mission Continues: An Overview Shot of the Vietnam War Wing:

I hope that those who read and hear about this far-reaching campaign to find and protect our nation’s war letters will be inspired to help us spread the word. You might have war letters—and, again, we preserve letters from every U.S. conflict, both by troops and their loved ones—stashed away in your home, and we would be honored to have them. We do accept photocopies and scans, but we prefer originals, and what many donors have told us is: “I made copies for myself, but I’m giving you the originals because I’m afraid that, down the road, younger members of our family will just throw them away.”

Visit the War Letters website for more information. You’ll also find, on the right hand side of the site, links to the virtual Museum of American War Letters, the trailer for “If All the Sky Were Paper” and a direct link to the “Behind the Lines” podcast.

And if you have something that you think is particularly unique, historical or special in some other way (and we value everything donated to us, but some letters, objectively, are especially descriptive or have an incredible “back story” to them), feel free to email me directly.

Again, you can assist us by spreading the word. If you have veterans in your family, ask them if they have any of their war letters. Even sharing our website link on social media or in other ways also helps us significantly.

A Final Word

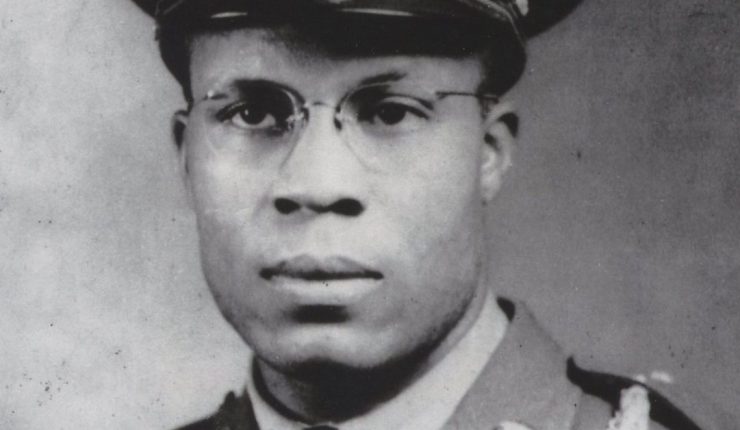

“At the very top of this post, there is a photograph of a soldier named Oscar Mitchell, and he was a major in World War II. Oscar wrote what I believe to be one of the greatest war correspondences ever written. His letter was a response to a friend, back in the States, who was “envious” that Oscar was serving overesas and part of history. Oscar, in no uncertain terms, replied that there was nothing romantic or glorious about what he was experiencing.

I’ll end with his words, as I could never articulate these sentiments more powerfully than Major Oscar Mitchell, himself:

“Dear Sylvia:

You say that you wish you were over here. Although most people think that they are “war conscious,” are they really? So far removed from the far-flung battle fronts, how can they be?

You are really “war conscious” when you see the airplanes, in formation, early in the morning, flying to meet their rendezvous . . . and then see this same formation returning in the evenings. But the number is not the same. Twelve went out, but only nine returned. You stand there, looking up, watching them fly into the distance; into and part of the horizon, then disappear.

You wonder, what really did happen? Those who went down in flames. Do they die as you see them in the movies? I don’t think so. Not with a smile on their lips and a happy gleam in their eyes, but rather painfully and with the knowledge that this is it.

You’d have to see the wounded streaming back from the front after a battle, above all, to see the light go out of men’s eyes. Young men shaking from nervous exhaustion and crying. Strong men they are, or were, who did not or will not have the chance, ever, to live normal lives.

People may think they know what war is like. Their knowledge is facts of the mind. Mine is the war-torn body, scared to soul’s depth. When I was in the States, war was far away, unreal.

I had read, I had seen pictures, but now I know.

Oscar”