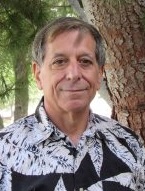

To protect 16,000 indigenous villagers deep in the Amazon rainforest, Hilly Kaplan is working his magic from 5,000 miles away.

The Chapman University professor is on the phone in his Orange County home, trying to get a vital piece of equipment moved from the Bolivian city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra to the remote town of San Borja – gateway to the rainforest villages. It’s Kaplan’s latest logistical challenge as he manages a globally significant research project during a worldwide pandemic.

For more than 18 years, Hillard Kaplan, Ph.D., a professor of health economics and anthropology, has led a research team of dozens as they gather groundbreaking health and history data. The project hinges on the symbiotic relationship the team has nurtured with the Tsimane – among the last people on Earth to still live a hunter-farmer-forager lifestyle.

Insights about humankind’s preindustrial past are in these Bolivian villages. Where muddy rivers flow and rutted roads impede, team members work year-round gathering data on aging, diet, lifestyle and health.

To keep the complicated research project on track, Kaplan has to maintain a delicate balance. He tends to the needs of the indigenous villagers, whom he cares about like family, while also meeting the demands of a project yielding highly prized information.

Never has Kaplan’s balancing act been more demanding.

Putting a Project on Pause to Safeguard Partners

In this time of the global COVID-19 health crisis, he and his team have shifted from health data collection to population protection. Team members scramble to keep the Tsimane and their neighbors, the Moseten, out of the crosshairs of the novel coronavirus. Which is why Kaplan needs to move that important piece of equipment – a biosafety cabinet for processing COVID-19 rapid tests. He had to get the cabinet specially built, then adapt it to fit in the back seat of Bolivian taxi cab for transport.

“These are minor problems compared to some of the other ones we’ve had to solve,” Kaplan says. “We’re constantly battling to get our people to the research site, because when it rains, the roads can be nothing but mud up to your waist.”

One time Kaplan’s truck slid into a ditch and he spent the night trying to sleep where the mosquitoes were so thick that they covered the windshield. He woke up at 4 a.m., walked a couple of miles and found a farmer, who helped pull the truck from the mud.

Why endure such headaches and hardships? That’s an easy one. The research is incredibly valuable, and the future of the Tsimane is at stake.

Plus, project partner Michael Gurven, Ph.D., is convinced, Kaplan just flat-out enjoys making the near-impossible happen.

“Hilly is great at taking things step by step, analyzing the angles,” says Gurven, professor of anthropology at UC Santa Barbara. “He has an amazing capacity to navigate it all – the meetings, the red tape, the obstacles. In some perverse way, I think he actually likes it.”

Tsimane’s Lifestyle Holds Clues to Healthy Aging

Since the Tsimane (pronounced Chi-ma-NAY) Health and Life History Project first launched in 2002, Kaplan and his colleagues have learned truckloads about how diet, exercise and lifestyle can impact overall health. They’ve found that 80-year-old Tsimane villagers have roughly the same vascular health as Americans in their mid-50s.

The Tsimane also have few cases of diabetes and hypertension, plus a near absence of stroke and heart attack. The link is clear: Villagers spend as much as seven hours a day being physically active. Their diet consists largely of non-processed carbohydrates that are high in fiber, while wild game and fish provide the bulk of their protein. There is virtually no smoking.

If the industrialized world emulated the Tsimane in diet and activity, it would save millions of lives and billions of dollars in health-care costs, Kaplan says. “We are our own worst enemies,” he adds.

The project’s findings on vascular health have been documented in high-profile peer-reviewed journals and have also garnered widespread mass-media attention. Those insights and many others are why the project has attracted grants totaling $8.5 million from the National Institutes of Health to also study brain atrophy, cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s among the Tsimane.

“The link between arterial health and Alzheimer’s is still unclear,” Kaplan says. “This is the first study that looks at tissue loss in the brain among an indigenous population.”

Project team members are eager to gather more of the data. But first they are acquiring real-time lessons in trying to safeguard a highly vulnerable population.

Crafting a Comprehensive Protection Plan

In the early days of the pandemic this spring, Kaplan and the project team of physicians, anthropologists and Tsimane leaders swiftly began putting together a detailed protection plan. Kaplan and Gurven recognized that their ideas might also be applied to safeguard indigenous populations elsewhere in the world. In the U.S., Navajo communities were already seeing spikes in coronavirus cases.

In May, the Tsimane Project’s report on its protection plan was published in the journal The Lancet. Since then it has been translated into Spanish, Portuguese and French so the plan might serve as a blueprint elsewhere.

By midsummer, COVID-19 reporting showed that one in every 2,300 infected indigenous Americans had died, compared to one in 3,600 white Americans. Among the most vulnerable are tribal elders, who are critical sources of cultural knowledge and traditions. Protecting these elders is an important part of the Tsimane Project plan.

Early steps in the multiphase plan focused on educating the Tsimane, who live in 95 communal villages. Flyers, town-hall-style gatherings and radio alerts encouraged social distancing and other prevention steps. A platform of rapid testing was developed, and crude gates were installed and staffed at village entry points.

“Self-isolating, building quarantine huts and moving them away from village elders – these are our best hope,” Kaplan explains.

Still, with increasing numbers of the Tsimane traveling to markets in San Borja, Kaplan and village elders knew their plan might be leaky.

“We weren’t so naïve as to think it would be foolproof,” Gurven says.

Markets Become Centers of Transmission

In recent years, more of the Tsimane have turned to selling fish, plantains, rice and other goods that they catch, grow or gather. During the pandemic, many have been willing to brave the additional risk of the marketplace to provide extra benefits for their family.

“Markets in Latin America have proved to be centers of transmission,” Kaplan says.

In July, Kaplan said, “We’re very nervous now. Trying to do something with COVID is like trying to get a tiger by the tail.”

By September, that tiger had pounced. In some villages, the infection rate was as high as 70%. In the communities closest to San Borja, “COVID spread like wildfire,” Kaplan says.

The team’s plan entered a new phase. Kaplan and his colleagues marshalled resources, and seven doctors started visiting the villagers, stepping up rapid testing and treatment. Nine Tsimane team members who were being trained as anthropologists started doing contact tracing and checking on those known to be sick.

“What’s particularly impressive is how few people have gotten really sick,” Kaplan says.

The Chapman professor is reluctant to dive too deeply into the numbers, with the COVID-19 crisis still evolving and his team still compiling data. But through the first two weeks of September, a broad picture was emerging. The Tsimane’s communal lifestyle was facilitating transmission, but their miniscule rate of chronic disease was translating to a very high rate of recovery.

“Our nightmare about penetration of the virus is smacking us in the face, although the worst nightmare about severe illness and death isn’t happening,” Kaplan said in early September. “We’re not through it yet. There will be a story to tell, it’s just premature.”

Project Grows from Humble Beginnings

The team’s coronavirus pivot is just the latest twist to the Tsimane Project. The story of Kaplan’s interest in the health and safety of the Tsimane goes back to its earliest days.

The study subjects and the Amazon setting landed on his radar in 1999 thanks to preliminary research done by Gurven when he was a grad student at the University of New Mexico, where Kaplan was then a professor. Gurven had backpacked across South America and was so fascinated with Amazonian culture that he want back to explore Tsimane villages.

He and Kaplan talked about starting a research project, but they had no idea how it would blossom.

“We thought it would be a year-long project – maybe a couple,” Gurven recalls. “Long-term ongoing research is hard under the best of circumstances – it’s just draining. If you’d told me two decades later we’d be doing CT scans in the Bolivian Amazon, I’d have said, ‘What?’”

Still, they knew the project had promise.

“Given how much focus there is on the chronic diseases of aging – and not just the physical but the emotional, the cognitive, the psychological – we knew this was a huge opportunity,” Gurven says. “What we have found so valuable about the Tsimane Project is learning about what life was like prior to the Industrial Revolution, when people were living off the land.”

A key reason the project thrives is the deep relationship the team has built with the Tsimane. From the start, Kaplan and Gurven took steps to involve village leaders in all decisions. Project members knew the team’s presence would have impact, but they were determined that it would affect the Tsimane only in ways the villagers wanted.

“We had no idea we were going to play such a large role in the health care of the Tsimane,” Kaplan says. “But very early on, we realized there was a complete lack of care. The hospital basically refused to treat the Tsimane for tuberculosis because they thought they wouldn’t complete the treatment and because the Tsimane had no money.”

So Kaplan started working with village leaders and Bolivian officials. One of the project’s health-care research participants, Long Beach Medical Center and the MemorialCare Health System in Southern California, provide expert advice to Bolivian doctors, who offer care in the villages.

“We started saving people’s lives,” Kaplan says.

Broken Bones, Snake Bites and Gratitude

Though the Tsimane have excellent vascular health, their active lives and rainforest environment lead to many injuries and illnesses. Three Bolivian doctors employed by the project began going from village to village, providing primary health care as they also collected data. A mobile lab processes routine tests. Broken bones, snake bites and hernias are common; with more complicated and emergency cases, the project pays for transfer to a Bolivian hospital.

“Over the past 18 years, there is almost no family in the Tsimane population that hasn’t had a life saved or seen a big difference in their well-being,” Kaplan says. “They have come to believe in our commitment to them, and that relationship of trust has benefited our science.”

The project has now gathered data on 8,000 people, providing robust information that Kaplan and colleagues have shared in about 100 scientific articles. The current team consists of 12 to 14 anthropologists and eight to 10 cardiologists, as well as cognitive health experts, infectious disease specialists and other scientists. In addition to Chapman, UC Santa Barbara and Long Beach Medical Center, other participating institutions include Arizona State University, USC, the Institute for Advanced Study in Toulouse, France, and Mount Sinai Health System in New York City.

At the hub of it all is Kaplan, whose project duties often begin at 5 a.m., whether he’s needed to find an oncologist to treat a villager diagnosed with bone cancer or to help thousands of villagers cope with the countless complications of a pandemic.

“I kind of feel like I’m an orchestra leader who doesn’t play any instruments,” he says.

For Kaplan, the project challenges are nothing compared with the rewards.

“It’s not something to which I expected to dedicate 20 years of my life, but then I didn’t expect to have a deep connection to so many lives and health-care problems,” Kaplan says. “It has become a fundamental part of our whole relationship with the Tsimane – that care is determined by the level of need and not by their contribution to the project. These are investments we’ve made – commitments we’ve made – and the reward is that the science we’re doing is unlike any other project ever done with a tribal population.”

Even without the scientific benefits, “the help we’ve given would justify my time,” Kaplan adds.

In a reflective moment, he recalls a four-day period when the project facilitated 20 cataract surgeries for Tsimane villagers. Their faces beamed with the gratitude of having their vision restored.

“Moments like that,” Kaplan says, “certainly make you feel good.”