In honor of Black History Month, the Escalette Permanent Collection of Art would like to highlight some of the incredible Black artists in the collection.

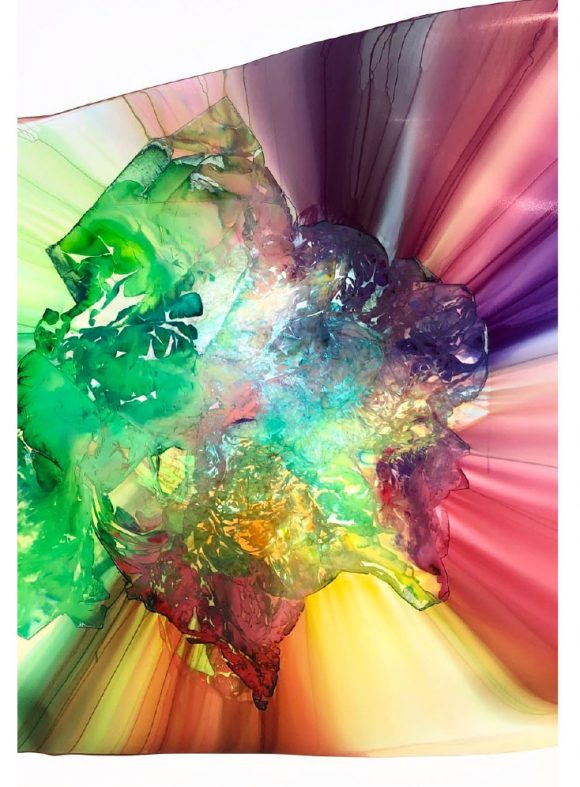

Maya Freelon Asante

Maya Freelon Asante is an award-winning African American artist who is best known for her lively, colorful sculptures that sometimes combine printwork with photography. Freelon’s work was described by poet Maya Angelou, her godmother, as “visualizing the truth about the vulnerability and power of the human being.”

All of Freelon’s artwork is dedicated to her grandmother, Queen Mother Frances J. Pierce, and is about Freelon’s experiences of living with her, remembering her as a child, or using the water-damaged tissue paper she found tucked away in her basement.

I hope I can empower girls who identify that way – publicly or not — that I made something out of nothing and they can too.

Asante says that her grandmother “let me know that I have purpose and she helped me access my own worth… Especially as a young black, queer female. I hope I can empower girls who identify that way – publicly or not- that I made something out of nothing and they can too. Trust and believe that what you’re doing in life has value.”

The water-stained tissue paper found in her grandmother’s basement in 2005 had an enormous impact on Freelon’s creative process. She was drawn to the expression of color and the physicality of the material and felt that the concept of watermarks was a natural and familiar concept. A few weeks after her discovery, Hurricane Katrina occurred, and she saw how the water forever altered, and left a mark, on the landscape. Since then, Freelon has been experimenting with “bleeding” tissue paper and witnessing how it’s destroyed or degraded through the creative process. Each of these pieces of tissue paper are altered in some away – soaking in and out of water, being ripped apart and put back together, thrown, stepped on – before being unified in an artwork, a practice that references her family’s history of quilt-making and tradition of preservation and resourcefulness.

“Each piece speaks to me as a memory of existence and resilience. Independently, a torn piece of paper seems like a scrap of trash, but once unified with others, the force is overwhelming,” says Asante.

Each piece speaks to me as a memory of existence and resilience.

Freelon’s tissue ink monoprints, like the one in the Escalette Collection, are created by saturating tissue paper with water to release the ink from the fiber. The tissue is then pressed onto a thick paper which permanently absorbs the ink. The paper and tissue are then mounted onto a potter’s wheel, allowing Freelon to stand above the work and use the tissue paper as a brush while the paper is in motion. As the wheel moves at different velocities, the ink spreads and mixes with the other colors to stain the paper in different spiral patterns that evoke the natural formation of islands or basins.

Freelon’s assemblages reside in collections around the world, from U.S. Embassies in Madagascar, Swaziland, and Rome, as well as the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill and the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Maya has completed residencies at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine, the Korobitey Institute in Ghana, and the Brandywine Workshop in Philadelphia. She earned a BA from Lafayette College and an MFA from the School of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Maya Freelon is currently an artist-in-residence at QueenSpace in NYC.

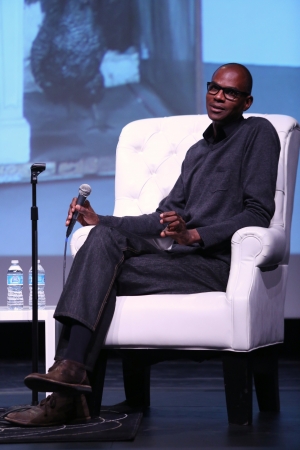

Rotimi Fani-Kayode

Rotimi Fani-Kayode was a photographer who used his art to capture the black queer experience, to reject homophobia, and to fight for equal political representation during the AIDS crisis. Fani-Kayode was born in 1955 in Lagos, Nigeria. His father was a politician and chieftan of Ife, the ancestral Yoruba capital. At age 11, Kayode and his family moved to Brighton, England to flee the Nigerian Civil War. He later attended Georgetown University and earned an MFA in 1983 from the Pratt Institute. He began his career in photography after moving back to England and founded the organization “Autograph: Association of Black Photographers.” This nonprofit helps black and minority photographers build careers and advocates for them in the mainstream.

“On three counts I am an outsider: in matters of sexuality; in terms of geographical and cultural dislocation; and in the sense of not having become the sort of respectably married professional my parents might have hoped for,” says Fani-Kayode.

On three counts I am an outsider: in matters of sexuality; in terms of geographical and cultural dislocation; and in the sense of not having become the sort of respectably married professional my parents might have hoped for

Much of his early work was created during the height of the AIDS crisis and responded to the homophobia in Thatcherite England and his home country of Nigeria. His photos expressed black queerness, focused on cultural identity, and acted as political calls to action. His photographs combine African and European iconography as a way to contest the marginal status of Yoruba culture and explore the position of the black body in Western society. In some images, Fani-Kayode incorporates elements of Yoruba spirituality into ironic signifiers of African “otherness” in a way that rejects the Primitivist themes of European modernism. Other images make reference to explicit eroticism and moments of intimacy or communion to present queer sexuality as an act of healing and survival.

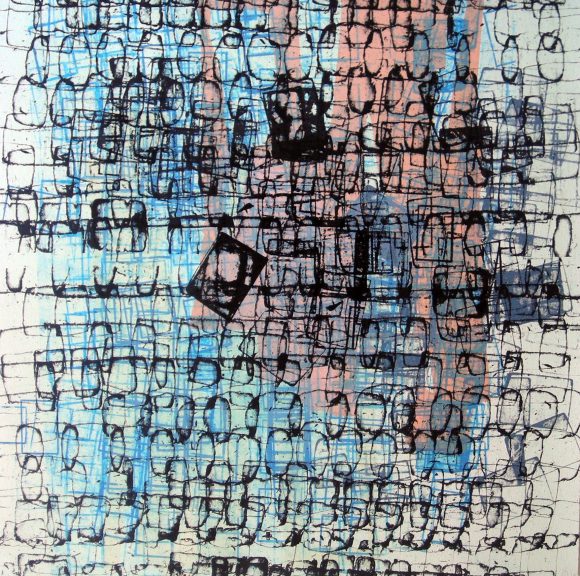

Mark Bradford

Los Angeles based artist, Mark Bradford, is well-known for his abstract style. Born in 1961, he grew up in a working-class family in an all-white suburb in Santa Monica with his single mother. Later on in his adolescence, he moved to South Central L.A., where he witnessed police brutality and racial turmoil. The disparity between the neighborhood of his childhood and that of his adolescence shaped his world-view and artistic interests. Much of Bradford’s work reflects or comments on the the struggles of race and poverty by uniting high art techniques with the visual material of popular culture.

Bradford is best known for his use of the discarded materials of urban life including remnants of found posters and billboards and graffiti stencils and logos. These materials, and the large-scale collages and installations they are transformed into, often respond to the impromptu networks of underground economies, migrant communities, and appropriations of public space, that emerge within the city. The seemingly organic, yet urban compositions Bradford constructs appears to mimic the layered growth of the streets, crowds, and diverse communities in Southern California.

He describes his work: “Think about all the white noise out there in the streets: all the beepers and blaring culture – cell phones, amps, chromed-out wheels, and synthesizers. I pick up a lot of that energy in my work, from the posters, which act as memory of things pasted and things past. You can peel away the layers of paper and it’s like reading the streets through signs.”

I pick up a lot of that energy in my work, from the posters, which act as memory of things pasted and things past.

Another of Bradford’s favorite materials, the paper hair-dying rectangles, bobby pins, and other suppliers used in hair salons, can be seen in the works in the Escalette Collection. Hair salons hold a personal significance to Bradford, who came from a family of hairdressers and worked at his mother’s hair salon after graduating from high school. By layering these unconventional materials, Bradford creates conceptual artworks that hint at his own excavation of emotional and political terrain

Mark Bradford has received many awards, including the Bucksbaum Award (2006); the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Award (2003); and the Joan Mitchell Foundation Award (2002). He has been included in major exhibitions at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (2006); Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (2003); REDCAT, Los Angeles (2004); and the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York (2001). He has participated in the twenty-seventh Bienal de São Paulo (2006); the Whitney Biennial (2006); and “inSite: Art Practices in the Public Domain,” San Diego, California, and Tijuana, Mexico (2005).

Bradford lives and works in Los Angeles and frequently gives back to his community. He is the co-founder of the Art + Practice Foundation, a non-profit organization that serves as an arts center for transitional youth. It has a large exhibition space and artists in residence, as well as mentoring, tutoring, therapy, and job placement programs in place for participants. He hopes to use art education to engage the minds of young people and allow them to interpret the world they live in.

We invite you to explore all the works in the Escalette Collection by visiting our eMuseum.

Wilkinson College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences is the proud home of the Phyllis and Ross Escalette Permanent Collection of Art. The Escalette Collection exists to inspire critical thinking, foster interdisciplinary discovery, and strengthen bonds with the community. Beyond its role in curating art in public spaces, the Escalette is a learning laboratory that offers diverse opportunities for student and engagement and research, and involvement with the wider community. The collection is free and open to the public to view.