It was the best possible news for a parent. No more signs of cancer in their 2-year-old daughter, a curly-haired toddler named Emily.

So Christopher Jerry breathed a sigh of relief, even as the oncology team prescribed one more short course of chemotherapy, a dose of extra protection for Emily. The future looked sunny. They started planning a going-home party.

But in the hospital pharmacy that day, a technician slipped up while preparing the IV bag containing Emily’s last treatment, accidentally adding an excessive amount of sodium chloride to the solution. The error transformed the treatment into a toxic concoction that proved suddenly fatal for the little girl.

That day Emily fell through the thin net of patient-safety procedures and practices that health professionals say puts all Americans at risk for preventable patient death and injury, a cause of more than 200,0000 fatalities in the U.S. each year.

His daughter’s death transformed Jerry into an activist.

“Emily’s legacy has been very much a catalyst for positive change in health care, in how we look at preventable medical error, how we learn from preventing medical error and, more important, how we respond to it,” Jerry says.

Strengthening Patient Safety With a Network of Diverse Experts

Chapman University’s School of Pharmacy (CUSP) has taken up the challenge of patient safety in force, leading an initiative aimed at strengthening that safety net. CUSP hosts a patient safety conference every spring, will launch an M.S. degree in patient safety this fall, and collaborates with the medical technology company Masimo on its Patient Safety Movement Foundation, which includes a network of partners, from hospitals to patient advocates like Jerry.

Included is a core curriculum that Chapman faculty helped write to improve patient safety education for students in medical, pharmacy and nursing schools and made available free to those institutions. It outlines numerous best practices that should be standard, such as the use of pre-mixed sterile solutions, which might have helped avert Emily Jerry’s tragic death.

It’s all part of a renewed response to the problem of medical error, says Ron Jordan, dean of CUSP. The problem isn’t new, but the fix has proved elusive. Twenty years ago, the Institute of Medicine published its revolutionary report “To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System,” and many of the difficulties it outlined still exist today.

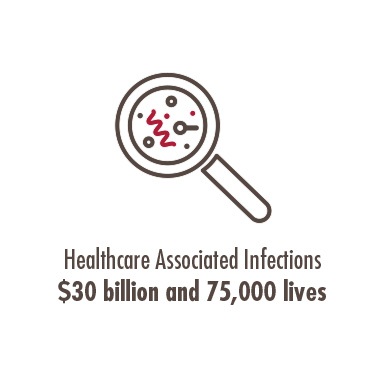

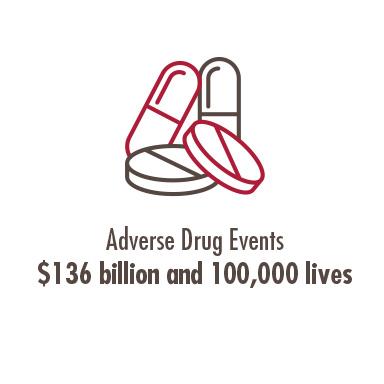

“That report said 20 years ago that we have to fix the healthcare system. Today, adverse drug events are still the third-leading cause of death in the country. Errors are happening in all kinds of places in healthcare delivery, however. There are wrong-side surgeries, hospital-acquired infections and several risks specific to long-term care facilities that need better attention. That tells me that we haven’t really done the job that we need to do in health care,” Jordan says.

Pharmacists Provide Front Line Defense as They Manage Chronic Conditions

Pharmacists take a natural lead in this effort, Jordan says. They can be on the front lines guarding against tragic drug errors like Emily’s, along with more common mistakes that occur with widely used medications millions of people need every day to manage chronic conditions or support recovery following surgery.

For example, medication management between hospital release and home care is a challenging period for many patients, and pharmacists can bring particular expertise to that window of time, he says.

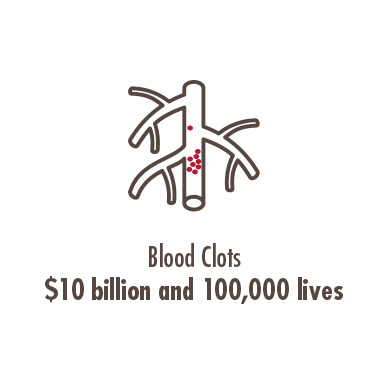

But that’s not the only reason patient safety is a major initiative at CUSP. Errors that cause avoidable complications, injury and exacerbated recoveries of all varieties add up to a hefty medical bill – some $19.5 billion a year in the United States alone. For change to take effect, every branch of health care must contribute to the effort, Jordan says.

But that’s not the only reason patient safety is a major initiative at CUSP. Errors that cause avoidable complications, injury and exacerbated recoveries of all varieties add up to a hefty medical bill – some $19.5 billion a year in the United States alone. For change to take effect, every branch of health care must contribute to the effort, Jordan says.

“It’s not only pharmacists, it’s physicians, hospitals, the system itself and its complexities,” he explains. “Every sector of health care needs to be involved.”

Christopher Jerry says efforts like those at CUSP will make a difference.

“Chapman is taking a leadership position from the educational standpoint and showing other institutions the direction that needs to be taken with our future leaders in health care,” Jerry says.

“This Involves Everyone, From the CEO to the Surgeon”

Sharing in that view is Joe Kiani, CEO of Masimo and founder of the Patient Safety Movement Foundation.

“This involves everyone, from the CEO to the surgeon to the pharmacist and the person making sure the operating room is clean,” Kiani says.

He’s optimistic that tangible efforts like the curriculum developed by CUSP will help, but Kiani still sees a long road ahead, although he’s encouraged by the UK’s stepped-up attention to the problem and hopes it will be replicated in the U.S.

“Those are the things that encourage me,” he says.

Christopher Jerry can’t help but look for hopeful signs of change, steadfast in his determination that no one ever suffer the fate of his beloved Emily. Lifesaving treatments are a modern wonder, but medical practice doesn’t end there, he says.

“We’ve come up with viable treatments extending the lives of people with all different types of diseases and conditions,” he says. “What good are they if we’re losing patients due to preventable medical error?”