Scientists, decades of authoritative research, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, generations of physicians and more than a few grandparents who remember the dangers of childhood diseases all agree on this fact — immunizations save lives.

And yet, a U.S. measles outbreak that began last winter endures and is linked to a growing number of parents who reject vaccinations for their children. This fall, seasonal flu shots again will be offered at multiple locations, from supermarkets to work places, and yet only an estimated 37 percent of American adults will roll up their sleeves, despite the vaccine’s proven ability to prevent flu.

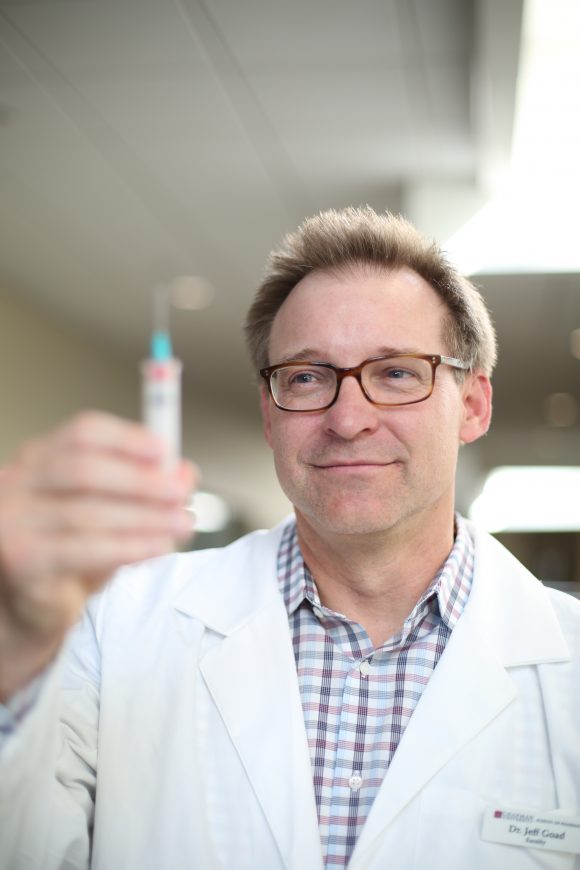

What’s going on here? In a nutshell, it’s more about social science than medical science, says Jeff Goad, Pharm.D., professor and chair of the Department of Pharmacy Practice at the Chapman University School of Pharmacy. Goad is past president of the California Immunization Coalition, winner of 2019 APhA Immunization Champion Award for Outstanding Career Achievement and a frequent lecturer on vaccination awareness and education.

Why do people think they know better than what research has proved?

We’ve had a mistrust of government that’s been percolating from the 1960s and on for a range of things, from supposed conspiracy theories to government cover-ups. It used to be that the media would investigate those kinds of stories and they’d be vetted, filtered and examined through a much more objective lens. Today there is no filter and there is no lens. The Internet can send you five different takes on the same story. It’s information overload for many people. The Centers for Disease Control becomes just one more voice. The cycle is so quick, the legitimate media sometimes get outpaced. People don’t know the difference between a CNN story and a mommy blog.

How do health educators combat this trend?

We think about it on a spectrum. You have the vaccine-compliant, who come in asking for vaccines and follow recommended guidelines. At the opposite end of the spectrum, you have the anti-vaccination groups. You’re going to make little to no headway with them. We actually try not to engage them. But what gets wrapped in the middle is what we call the vaccine-hesitant. That’s the group we need to work with. The vaccine-hesitant are moms and dads who’ve heard something on a talk show or read something on the Internet that makes them hesitant to vaccinate their child. But when you meet them where they are and present them with the facts, they usually choose vaccination. Fortunately, there are more people who get vaccinations for their children than not.

If most are vaccinated, why are unvaccinated children a problem?

Since measles is highly contagious, even a small number of unvaccinated kids can set off an outbreak. For example, a child with measles will infect around 12 to 18 non-immune people, who can then infect 12 to 18 more, and on it goes. If you increase the number of vaccinated (considered immune), that child with measles just has less people to pass it on to, and eventually the disease runs its course before they can infect anyone else.

What educational approaches work well?

I’ve worked with many different groups on this, from the Centers for Disease Control to the Immunization Action Coalition and lots of community-based groups. The universal theme is “fight fire with fire.” For example, since the anti-vaccine group uses personal stories to distort the facts, our immunization coalition created a series of videos of parents whose kids and other loved ones have been injured by the diseases that could have been prevented through immunization.

What makes this approach effective?

It’s difficult to relate to just numbers. Anytime you’re talking numbers, you must have a story with it — something they can contextualize, otherwise the message is not going to stick. Telling people that the flu killed almost 80,000 people in the U.S. last year, as amazing as that sounds, is not as powerful as showing a story of a mom recalling when she lost her little girl to what she thought was a cold but turned out to be influenza.