The reception that follows the awards ceremony for Chapman University’s annual Holocaust Art & Writing Contest is full of contrasts.

Holocaust survivors with canes, walkers and the aches and pains of age tread slowly but diligently into a light-filled party tent set on a large swath of lawn. Hundreds of middle and high school students swirl around them, eager to meet the survivors they’ve encountered through their oral histories. Students lean in to hear the soft voices and accounts of survival, escape and loss. In the next moment, the elders smile for photos captured on cell phones. A traditional klezmer band plays nearby, and nearly everyone grabs a kosher hot dog or lemonade. The springtime scent of new grass perfumes the air.

But everybody here also understands that what brought them to this pleasant afternoon in a big airy tent is one of history’s darkest chapters – the genocide of 6 million Jews during World War II. It’s a complicated mix of realities – particularly given the rise of anti-Semitic activity in the United States and around the world.

But those complications offer a life lesson, too, says Marilyn Harran, Ph.D., professor of history and director of the Rodgers Center for Holocaust Education.

“Probably more than most of us, the survivors know how to appreciate each day,” Harran says.

Still, it’s not easy. None of this is easy.

“For them to tell those stories and share those memories is very difficult. They do it because there is something at the very core of it that’s important for other people to know,” Harran says.

That duality of spirit is at the heart of what the Rodgers Center has achieved with the contest, which marked its 20th anniversary in March. To understand the Holocaust, or any moment in history, one must attend to the human stories – the good, the bad, the why, the how and the somewhere in between that complete the picture. So through the years, survivors and witnesses have devoted time and energy to tell their stories on video, in media interviews and every spring at Chapman when they meet personally with the contest participants.

Profound Impact

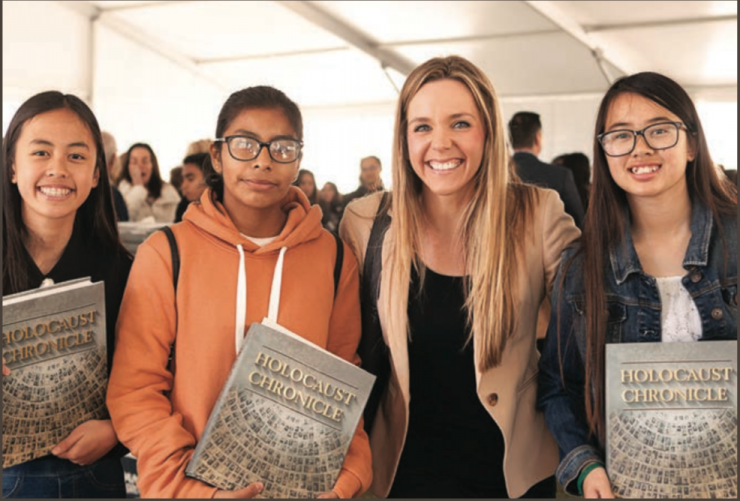

Today the contest attracts some 8,000 participants from 26 states and 12 countries. Several hundred travel to the Orange campus each year to attend the awards ceremony and reception. Reactions like that of middle school student Ezekiel Torres are typical. He and fellow classmates toured Chapman’s Sala and Aron Samueli Holocaust Memorial Library and later stood spellbound while an 89-year-old man described how his family escaped the Nazis and survived in hiding for more than two years until the end of World War II.

“Just wow. Wow, wow, wow,” Torres said. “Most of the time I have words to say all of the time. I’m just left with nothing. I’m left in awe at the stories that the survivors have to tell.”

Then he paused and said that of course he would tell others what he had learned, starting with his family “as soon as I get home.”

That, in a nutshell, is what the contest has always been all about. Launched as an essay competition in collaboration with The 1939 Society, an organization of survivors, their descendants and friends, the contest invites students to watch videotaped firsthand testimonies from people who lived through the genocide and then respond to a specific memory through creative expression. Specifically, that means participating schools dedicate time for students to focus on a videotaped testimony of their choice and then create prose, poetry, art or film to share what they personally gained from the experience.

We’re overwhelmed by the numbers and the horror

The second part of that challenge is that the students go forward as “witnesses to the witnesses” – an increasingly poignant call to action as that generation passes on.

None of this is easy.

“We’re overwhelmed by the numbers and the horror of the Holocaust,” Harran says.

Beyond Numbers and Dates

For many students, that summary approach of numbers and dates is the extent of their understanding of this difficult history, says Jessica MyLymuk, assistant director of the Rodgers Center for Holocaust Education. MyLymuk manages much of the logistics of the contest and follows Holocaust educational trends in secondary schools.

“What I see is that it’s not a well-rounded education. The focus is on the death and destruction and it’s not on the causes. It’s not about how any of it started. It’s focused on the big numbers. It puts up a barrier,” she says.

By its very design, the contest counters that. Brittany H. Urig, a practicing attorney who has taught at Chapman’s Fowler School of Law, received first prize for her prose in the contest’s fourth year and was a guest speaker during the recent anniversary awards ceremony. She credits her participation in the contest for helping to shape her into who she is today.

Advancing Holocaust Education

“It has been a huge theme in my life. It was the first time I met Holocaust survivors, obviously. It was the first time I shared my voice with hundreds of people. Both have had a lasting impact on me,” she says. “It gave me a perspective of what people are capable of and how important it is to be the best human you can be. That perspective has never been lost on me as I practice law.”

Because of the contest, Urig was inspired to become a law fellow with Fellowships at Auschwitz for the Study of Professional Ethics in the summer following her graduation from law school. When she toured a museum, she was pleased and proud to see that the subject of her essay, a Jewish teacher and physician who refused to escape the Nazis and instead went with his students to the gas chambers, was remembered in the displays. (In the contest’s early years, students could opt to base their essays on biographical accounts of Holocaust victims.)

“I often think back on him and the choice he made … and his belief that what was happening was wrong,” she says.

Meeting Survivors

Friendships sometimes blossom as well. Hailey Shi, who won in multiple categories in middle and high school, still corresponds with Engelina Billauer, whose story she portrayed in an award-winning artwork recalling the day Nazis hauled away Billauer’s deaf parents, who signed their goodbyes through the back of a bus. Their meeting still resonates.

“I happened to see both her and her late husband, Richard, arrive before the ceremony started, so I decided to walk over to introduce myself. Everything happened very quickly,but I will always remember how Engelina’s eyes lit up when I told her that I was the girl who chose to tell her story,”she says.

Indeed, the lion’s share of the awards day is spent connecting all the students with the survivors, furthering the mission of education. The morning begins with students touring the Samueli Holocaust Memorial Library. Harran and a team of volunteers lead the students through the exhibits.

Timely Messages

Although the contest is always relevant, this year it was particularly timely. The previous week a video of area high school students playing beer pong with plastic cups arranged into the shape of a swastika went viral online and drew national attention.

“In a time of increased acts of bigotry and anti- Semitism, including here in Orange County, and a decreasing knowledge of the Holocaust, you have learned that the Holocaust is not about numbers but about people,” Harran told the audience that packed Memorial Hall in March. “You know what the ideology of the swastika did to people and what it meant to someone your age to have to wear a yellow star. You will be the ones who will stand up and speak out because of what you’ve learned.

The students who participated in this contest know that a swastika is never a joke.”

There is no replacement for such an experience, says art teacher Maria Diaz from St. Mary’s School in Aliso Viejo, Calif. One of Diaz’s students was among the contest winners.

“Listening to their experiences firsthand is amazing,” Diaz said as she watched her students hurry around the tent to speak with Holocaust survivors.

“This is what teaching and learning is to me,” Diaz says. “Empowering our kids to be those who go out and tell the stories about what went on so we don’t make the same mistakes again.”

Exhibition Showcases Student Work

Chapman University’s Rodgers Center for Holocaust Education, in partnership with Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust, presents a special exhibition featuring 20 years of prize-winning entries from Chapman’s annual Holocaust Art & Writing Contest.

The exhibition, titled “Messengers of Memory,” includes first-place entries in prose, poetry, art and film representing the more than 100,000 middle and high school students who have participated in the contest over the years. Initially regional in its outreach, the contest this year includes students representing 26 states as well as 12 countries and five continents.

The exhibition was unveiled at an April 7 reception. It remains on display through August 2019.