One download at a Time

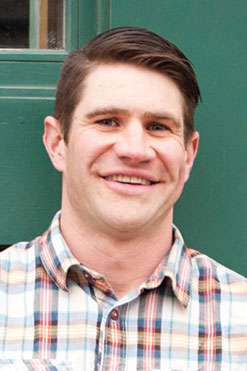

With his popular podcast, Paul Churchill ’05 “shreds the shame” as he empowers a growing support community.

Listen to Paul Churchill’s first podcast episode, “I’m an Alcoholic.”

When Paul Churchill ’05 sits down alone behind a microphone in Bozeman, Mont., a community starts to come alive.

“My name is Paul Churchill, and I have a confession to make. I’m 32 years old, I live in southwest Montana. I share my condo with a standard poodle named Ben. And here’s the confession. In reality, I’m terrified to say this. And I’ve known this for a fact, what I’m about to say, for 10 years, but every time I say it, I’m still getting used to it. It stings. It’s something I’ve held hidden, deep dark inside my realm of secrets. But here it is: I am an alcoholic. I have been sober for 156 days.

Those are the words that launched the “Recovery Elevator” podcast when it first aired on Feb. 12, 2015.

More than 2 million downloads and 200-plus weekly episodes later, Churchill is more than four years sober, and “Recovery Elevator” is an entrepreneurial success that embraces technology as a way to create communities that help people learn to live a life without alcohol.

“I think I’m going to do ‘Recovery Elevator’ for the rest of my life,” he said.

A Different Approach

What began as a way for Churchill to carry himself through the challenges of his first year of sobriety has evolved into a multifaceted business. The podcast has attracted multiple corporate sponsors, and “Recovery Elevator” offers listeners paid subscription-based access to private online communities known as Café RE, along with “sober travel” group tours, including a trip to Peru.

As the audience grew, Churchill realized his mission had become to “shred the shame” caused by the stigma surrounding substance-use disorders, and to help people manage a life without drinking by creating connections with others.

Excessive alcohol use leads to about 88,000 U.S. deaths each year and is involved in almost a third of driving fatalities. An estimated 15 million American adults have an alcohol-use disorder, but fewer than 10 percent receive treatment in a given year.

“Alcohol does not discriminate,” said Churchill, whose weekly podcasts now include a listener each week who wants to share their story. “I’ve interviewed doctors, lawyers, engineers, even the CEO of a Fortune 500 company.”

What Churchill inadvertently discovered is how technology can ease the path to sobriety.

Taking a first anxious step into an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting or committing to a rehab program can be frightening. But by listening privately at first, then signing up for a private Facebook group or going onto the podcast as a guest, people often find they become comfortable enough to be more open in their journeys and many times eventually find their way to AA or treatment if they need additional support, Churchill says.

The listeners on Churchill’s warm, witty and bantering podcast — be prepared for occasional references to the band Third Eye Blind — are not who some people might expect them to be. They are mostly in their 20s, 30s and 40s. Many are in relationships or are the parents of young children. Most are doing well in their careers, though many have had personal or work setbacks at some point. But whether Churchill is talking to Elaine with 15 days sober, or Ronnie with 25 years, his refrain is the same: “We can’t do this alone.”

“When I graduated Chapman, becoming an alcoholic was not part of the plan, but you’ve got to roll with the punches.”

An Entrepreneur at Heart

At Chapman, Churchill majored in business administration and knew he wanted to become an entrepreneur. Also a member of the football team, he was often the life of the party, but not in the way you might think.

“I was always DJ’ing at Chapman. I would be on the microphone and just felt comfortable,” he said. “It’s kind of a God-given talent.”

Starting his own businesses was always in the cards — “That’s just how I’m wired. I was the kid who had lemonade stands,” he said.

“I loved at Chapman that I could go talk to any one of my professors,” Churchill said. “I took advantage of the office hours, and it was a small school. That’s what they sold, and that’s what they delivered. They delivered a personalized education.”

Churchill’s current roster of successful businesses includes a thriving wedding DJ company, adult sports leagues and an arcade business. But it was his first venture, buying and operating a bar in Spain, that set him on a harrowing path that ultimately led to sobriety, or what he calls “my most crowning achievement in life.”

“When I graduated Chapman, becoming an alcoholic was not part of the plan, but you’ve got to roll with the punches,” Churchill said wryly.

His story, which he has told at speaking engagements like TEDx Bozeman, has dark turns, like many stories of addiction.

“I was hoping to leave my drinking problem in Spain, that it would stay there, but guess what? It came with me when I moved back home to Colorado. From there, I actually tried another geographical cure, I went from Colorado to grad school at the University of Washington, hoping my drinking problem was going to stay in Colorado, but darn it, it came with me to Washington. In 2010, I started to realize alcohol might be the problem,” he said.

“I had been a success as an entrepreneur, and pretty much everything I’ve done, but something was holding me back, and in 2010 I decided to quit drinking, and I made it 2½ years, and then I drank again,” he said.

Churchill moved to Bozeman after earning a master’s degree in intercollegiate leadership at the University of Washington, launched more businesses, and stopped drinking for what he intends to be the final time on Sept. 7, 2014.

In those early, shaky months, “I kind of had a moment of clarity, like oh my gosh, if I don’t do something extremely different, I am going to drink again and all these businesses that I built, they’re all going to come tumbling down,” Churchill said. “The signs were there. It was already starting to happen.”

The podcast started simply as a way to hold himself accountable, he said.

“I didn’t really care who listened. I literally had no intentions of turning it into a business and turning it into what it is today. But I slowly started checking download numbers and people were listening. Then I got a first email and then a second email. Then about 100 episodes in, ZipRecruiter sponsored it, and now we’re getting more and more.”

A Continuing Quest

Though Churchill attends AA meetings, his approach is that people should find whatever works for them. His exploration of recovery continues, with well-researched introductions on the podcast to topics such as medication-assisted treatment, the relationship between alcohol and anxiety, and post-acute withdrawal syndrome, which includes symptoms such as anxiety, depression or difficulty concentrating that can persist many months into abstinence. He discusses mindfulness, how to date in sobriety and how to stay sober during the holidays. He even talks about whether to “break up” with the word alcoholic. (The current edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual prepared by the American Psychiatric Association uses the term “alcohol use disorder.”)

With no formal training, Churchill is quick to say he doesn’t give treatment advice and is not an addiction counselor.

“It took me a while to figure this out, but the product I’m providing is community,” he said. “I bring a lot of like-minded people together in one place.”

Every time he talks about recovery, whether on the podcast, in an interview or in day-to-day life, he knows there is a chance people will recognize themselves.

“Even in college, there will be people at Chapman who say, ‘Oh my gosh, I need help,’” he said.

“Somebody’s going to read this, and I want to get the point across that they’re not alone. If you’re struggling with alcohol, you’re not alone and feel free to reach out to myself or just tell yourself, ‘I’m not alone.’ There are a lot of people going through this, and we harbor this secret. I know for me, it was my deepest, darkest secret for about a decade. Just coming out about it was so empowering.”

Resources at Chapman for students concerned about alcohol or drug use can be found through Student Health Services and P.E.E.R. (Proactive Education Encouraging Responsibility). In addition to area AA meetings, there also is a student AA organization on campus called the Bill W. Contact the office of the Dean of Students for information.

Artistic Approach

With their graphic novel and music video, pharmacy students reimagine outreach, spreading a viral message of prevention and intervention.

Narcan, Suboxone, Antabuse, Vivitrol, Campral. Those are just a handful of the array of medications pharmacists dispense for the urgent treatment or longer-term recovery of people addicted to drugs or alcohol.

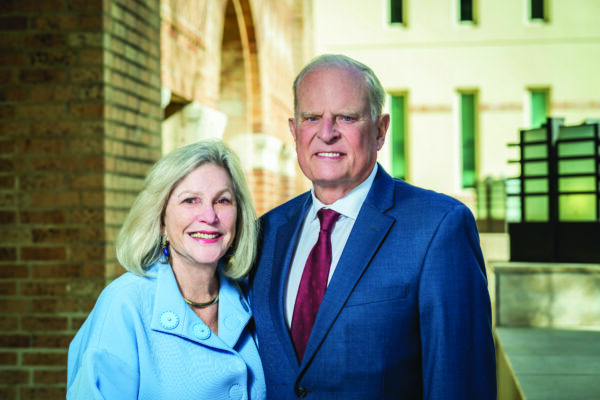

Yet a pharmacist’s role can be much broader. “We’re not just behind the counter,” said Mary Gutierrez, Pharm.D., a professor of pharmacy practice at Chapman University School of Pharmacy (CUSP).

Clinical pharmacists work directly with physicians and patients in healthcare settings, and many pharmacists play a role in educating patients and the public. Driven by these education goals, CUSP students are using their creative talents to target prevention and intervention in the treatment of drug and alcohol abuse.

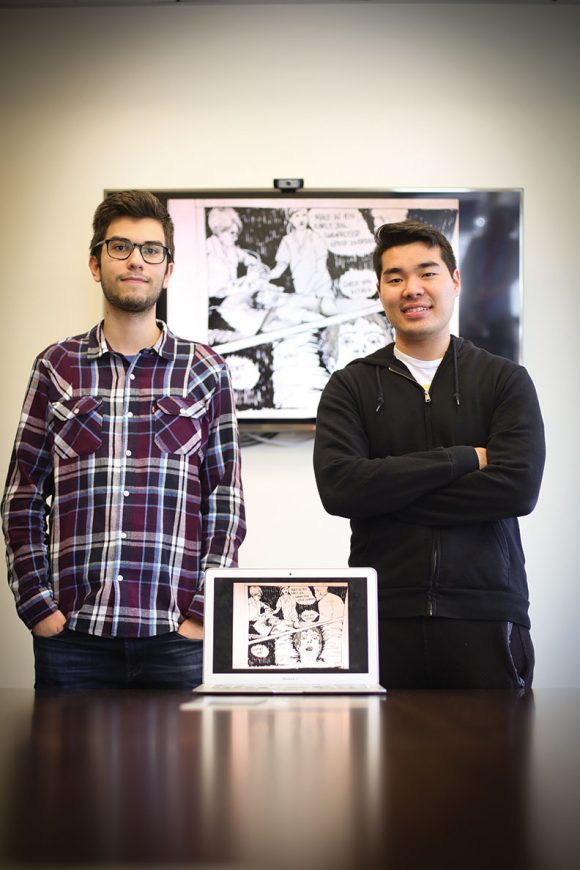

In one project, Vladimir Kozhemyakin (Pharm.D. ’20) and Rachana Poch (Pharm.D. ’20) have worked with a recovering addict and an illustrator on a graphic novel. The work tells the story of Clay Keena’s journey from three near-death overdoses to recovery and a full life as the father of a young child. The team plans to publish the graphic novel digitally so it can be easily shared on social media.

“I wanted it to be a digital product and not print, because printing can only be sent to so many people,” said Gutierrez, adding that the project is aimed squarely at prevention of substance-use disorders because recovery can be difficult and relapses are common. “This is free, and I can send it to junior high schools and high schools, and the kids can share it,” she said. “We can have a wider distribution and save lives.”

The students’ introduction to Keena, a man seeking to help others by telling his story of addiction and recovery, came in a class led by Gutierrez, who also teaches in the chemical dependency treatment program at Mission Hospital in Laguna Beach. She often meets patients during detox, when they are frequently prescribed anti-anxiety or anti-seizure medications to treat withdrawal. With expertise in psychiatric pharmacy as well, Gutierrez knows patients being treated for addiction often have been self-medicating for underlying mental health conditions or to escape feelings from past traumatic experiences, and she works to help her students understand that.

“Meeting Clay for the first time, it was really kind of an eye-opener,” Poch said. “I never had met someone who overdosed, and to hear all the stories he went through with his family and in the Army, it made me see that people go through a lot. It made me feel for him in a lot of ways. Just understanding how much drugs did to him and his life inspired me with this comic book and the project we’re taking on.”

“I never had met someone who overdosed, and to hear all the stories … It made me feel for him in a lot of ways.”

Under the guidance of Gutierrez, Poch and Kozhemyakin made the graphic novel the centerpiece of an elective capstone project.

“Basically, the only time we ever see drug abusers would be in a textbook definition, clinical cases, all written on paper,” Kozhemyakin said. “Now to see someone live, giving the physical story and description. … It made us more aware of how important this issue really is.”

Another group of CUSP student songwriters is seeking to make a music video of their composition focusing on the life-saving potential of naloxone, the opioid overdose rescue drug known by the brand name Narcan. Many people don’t know naloxone can be dispensed by pharmacists in California without a prescription – a policy developed to try to increase the odds the drug is on hand when someone overdoses.

The project’s lead singer is Samantha “Sam” Isidro (Pharm.D. ’20), who like Kozhemyakin entered CUSP through Chapman’s Freshman Early Assurance Program, a degree pathway that allows academically exceptional high school graduates to complete undergraduate study and a Pharm.D. degree in five years.

Isidro and fellow students Dustin Le, Jordan Stokes and Tiffany Chuang – all on track to earn Doctor of Pharmacy degrees in 2020 – are collaborating under the guidance of Jerika Lam, Pharm.D., an associate professor of pharmacy practice. The students have earned an educational grant from the California Society of Health-System Pharmacists to complete the video and hope to find students from Chaman’s Dodge College of Film and Media Arts to collaborate.

“We know that music and videos will connect with the youth of America,” Lam said. “We hope that our naloxone music video will have a far-reaching, significant impact and educate them on how to use it to save the lives of their friends and loved ones.”

Body of Research

Dmitry Foox (DPT ’18) and his Chapman physical therapy partners make the case for purposeful movement as a critical component of addiction treatment.

Dmitry Foox (DPT ’18) has always known he wanted to help people. After winning a battle with drug addiction eight years ago, Foox discovered a healthcare calling in physical therapy. Now he’s building his professional life around a mission – “to create a world in which recovery from addiction includes healing of the body.”

Recently Foox launched a practice called PHYSrecovery with two of his classmates from the Chapman University Physical Therapy program – Noel Santayana (DPT ’18) and Darren Wong (DPT ’18).

“The goal is big – to make physical recovery a standard practice of care at addiction recovery centers,” says Foox, president and CEO of PHYSrecovery. “I don’t see it as a lofty goal. I think it’s very practical.”

Foox knows of only one other clinic – Empowered Therapy and Wellness in Florida – that uses physical therapy to treat addiction recovery. Consulting with that clinic has helped PHYSrecovery clear some early hurdles and acquire its first clients. Thanks to the mentorship, PHYSrecovery opened its doors years before Foox expected it would possible.

Foox’s bushy beard and passionate advocacy give him an uncommon presence as he visits Southern California drug and alcohol treatment centers, making the case for physical therapy as critical tool of recovery. His story is just as distinctive.

“Before I got into PT school, before I was a physical therapy aide at Cedars Sinai, before I started taking PT prerequisite courses at community college, I realized that physical therapy was an important part of my own experience with recovery,” he says.

Almost a decade ago, Foox fell into addiction as a pre-med student, which sabotaged his studies and derailed his plans to become a doctor. He entered a drug treatment center, where he received professional counseling and spiritual support that helped modify his behaviors, but no one on his recovery team was trained to help him heal from the physical repercussions of addiction. Foox says it wasn’t until he committed to improving his physical health and fitness that his life turned a corner. He still draws on the experience as he works on his own exercise-reward formation model, for which he plans to seek a patent.

“You have to take an interest in something, and for me it was that I wanted to get moving, to get fit,” he says. “I started to feel the rewards of purposeful movement.”

It took hard work and persistence for Foox to find a new academic path. That led him to Chapman, where his research passion took flight and he found a mentor in Jacklyn Brechter, Ph.D.

“Dmitry has a unique perspective of bringing substance abuse into physical therapy,” says Brechter, associate professor of physical therapy in Crean College of Health and Behavioral Sciences. “No one out there had developed a systemized, standardized process, and it was interesting to see how he would walk through it – proving a need and seeing if physical therapy could be part of this process.”

It doesn’t hurt that Foox “is unbelievably motivated,” Brechter adds.

“When I assigned him something or asked him to do a literature review of the research, he’d always come back with more than was expected,” she says.

For his part, Foox says he was simply following a singular vision.

“Every opportunity to do a presentation for my peers in PT school, you better believe I did it on something addiction-related,” he says. “I was establishing a foundation of, ‘This is going to be my specialty.’”

As he transitions from student to practitioner and entrepreneur, Foox is grateful that “Chapman saw potential in me when no one else would, and accepted me because they saw evidence of my growth after my battle with addiction,” he says.

Now he and his colleagues are pouring themselves into building their business model and growing their fledgling practice. All during his journey, Foox says he’s eager to tell his story.

“I had a friend tell me I needed to impact a larger audience, and I’m OK telling the ugly parts of my life,” Foox says. “I humanize myself and other people by sharing my story.”