Vidal Arroyo’s path to becoming Chapman University’s first Rhodes Scholar has enough of those what-if moments that listeners to his story can’t help but wonder at the turning points.

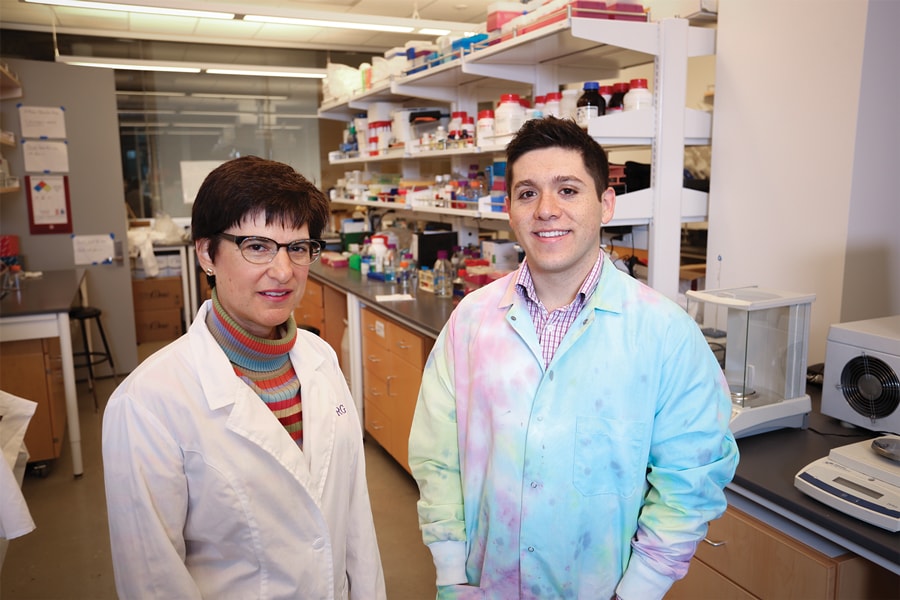

As late as his junior year of high school, Arroyo ’19 wasn’t considering higher education, but high school friends were busy taking SATs, so he did, too. He aced them. His first year at Chapman he enrolled in a molecular biology class, where he caught the attention of Melissa Rowland-Goldsmith, an associate professor of biology, who suggested that with his brand of focus and determination, he should consider research. So he started down that path.

He continued to study with Rowland-Goldsmith, Ph.D., who focuses on pancreatic cancer research. But Arroyo was intrigued by the work of Jake Liang, Ph.D., a School of Communication professor who researched human-robot interactions, so he joined that lab team. Then heartbreak struck. Liang was diagnosed with cancer and died at age 37. In the days that followed, Arroyo felt called to focus on the only path that now made sense – cancer research.

“My parents have always raised me with the idea of duende, which in Spanish means passion or soul. It’s the idea of pursuing something because you’re passionate about it,” he says. “Before Professor Liang’s diagnosis, I didn’t really have that connection with cancer. Seeing him die of that disease so young was just really shocking to me. It felt almost like a social responsibility. I decided I’d use whatever talents I have to change this for others. I decided I’m going full force. I’m going to be a cancer researcher.”

In October, that journey will continue at Oxford University, where the first-generation college student who commutes by train because he can’t afford a car will complete graduate work and study the applications of data science to improve colorectal cancer treatments. While at Oxford, he’ll also complete a master’s program in theology, with a concentration in science and religion. As a 2019 Rhodes Scholar, Arroyo is a member of the most diverse American cohort ever chosen by the selection committees. Almost half of the winners are immigrants or first-generation Americans.

For Arroyo, who grew up in south Orange County, it’s all new territory. The biochemistry and molecular biology major hadn’t heard of the Rhodes before he was encouraged to apply by Julye Bidmead, Ph.D., director of Chapman’s Center for Undergraduate Excellence. Then he read about the prestigious scholarship whose winners have included President Bill Clinton, Supreme Court Justice David Souter and Susan Rice, National Security Advisor to President Obama.

His first thought was, “What chance do I have?” With a smile, the former high school wrestler adds, “I decided go big or go home. Wrestling taught me that mentality. It’s the same mentality that got me through school.”

In addition to his studies and research, Arroyo is founding president of Chapman STEMtors, a 100-strong campus club that conducts science programs for middle school and high school students in at-risk neighborhoods. He also works as a peer advisor and maintains a 4.0 GPA.

Rowland-Goldsmith recalls that Arroyo visited during her office hours after she returned the semester’s first batch of graded quizzes. Arroyo had an A-minus but wanted tips for developing study skills so he could do even better.

“Vidal is truly one of the most tenacious students I have ever worked with,” she says.

Arroyo credits his faith and the encouragement of all his Chapman mentors along the way.

“The professors believed in me more than I did, and that’s been incredible,” he says. “It’s really a testament to the amazing environment here and the ability for someone to see potential in someone else.”

Cancer

Does not

Discriminate

Shadowing physicians (at CHOC Children’s hospital), my images of sunny, safe California were marred. Chemotherapy cured many children of cancer, but it also caused a wide range of long-term complications. Some survivors lived on synthetic hormones to compensate for damaged organs. Others developed obscure arrhythmias that were not present before. Many, like my former self, were obese. Cancer changed their lives forever, haunting them in ways unimaginable.

At CHOC, my interest in medicine expanded. This led to a research project with Dr. Jake Liang, a Chapman professor, to investigate how communication strategies could reduce physician burnout. My passion for research grew, but our time together was cut short: Dr. Liang was diagnosed with stage IV colorectal cancer. When he broke the news to me, I cried. Dr. Liang had two sons, and he always had an apple on his desk. He biked to work and maintained a healthy weight. Nonetheless, cancer took his life 10 months later at 37 years old. Through him, I learned that cancer does not discriminate. Cancer does not care if you’re healthy, ill, young, old, wealthy, or poor. I was infuriated by this reality, but my inability to treat Dr. Liang or prevent his death is what drove me to dedicate my life toward cancer research and clinical service as a physician-scientist.

When I decided to attend Chapman, I made the decision to commute two hours a day by train due to finances. However, I have not let this barrier nor others stand in the way of my calling as a cancer researcher. Just as I have dreamt bigger and fought harder for my education and the education of others, I will continue to dream bigger and fight harder for a better future for cancer patients. As Chapman University’s first Rhodes Scholar, I will continue my pursuit toward a day where no child will have to suffer from the late effects of cancer.

Excerpted, with permission, from Arroyo’s Rhodes Scholarship personal statement.