The 2017-2018 flu season was brutal, led to more than 80,000 U.S. deaths and sent an estimated 900,000 people to the hospital with complications, according to the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases.

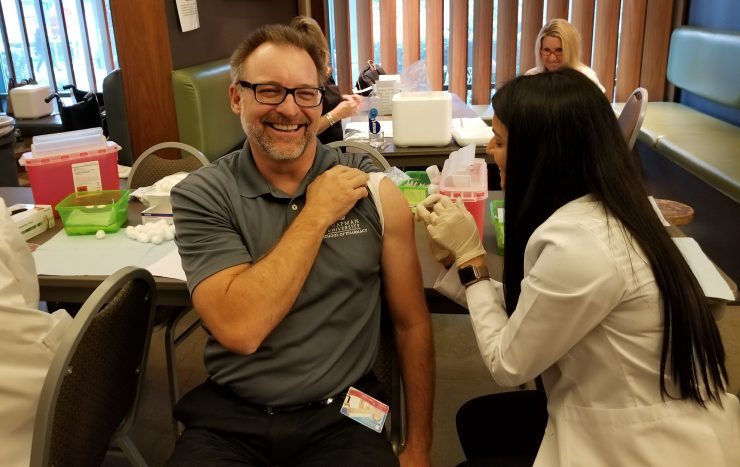

The only silver lining is that more people will roll up their sleeves and get a flu shot this year, says Jeff Goad, Pharm.D., professor and chair of the Department of Pharmacy Practice at Chapman University’s School of Pharmacy.

A vaccination success story, especially significant as we mark the 100th anniversary of the 1918 Flu Pandemic, right? Yes and no. Because here’s what else Goad can predict. There’s nothing like a mild flu season to put people off flu vaccinations the following year. Public health researchers know the cycle well.

“People think ‘Oh, I didn’t get the flu last year.’ Or they don’t recall a lot of deaths or debilitating hospitalizations,” he says. “You need a major outbreak to stir up vaccination rates. That’s true of other preventable diseases, too. When measles hit Disneyland, we got a whole new law (requiring vaccination of children). It’s unfortunate that that’s what it takes to get people to modify behaviors. Prevention is not something Americans are used to.”

Herd Immunity Helps

But when it comes to influenza, vaccination – especially among children and healthy adults – is the best prevention for the overall population, Goad says. When healthy young people are vaccinated, they develop a strong immune response. If enough people don’t get the flu, it makes it hard for the virus to get around. It’s what virologists call “herd immunity.” And that’s particularly helpful to the elderly, young children, heart patients, diabetics and others with immune-comprising conditions for whom the flu vaccine can be less effective.

“People often wonder how Influenza causes so many deaths. Mostly, it causes chronic conditions like heart disease and chronic lung disease to get worse as well as causing bacterial pneumonia in older adults,” he says.

Not that youthful vigor is an automatic defense against this virus. Healthy adults aged 20 to 49 were hardest hit by the 1918 flu and again in the 2009 pandemic.

“As we talk about the 100th anniversary of the 1918 flu, it’s always good to learn from history. New flu viruses can suddenly pop up in the population,” he says. “And even though we might have a mild flu season one year, there’s no way to predict what it’s going to be the following year.”

Flu Forecasting

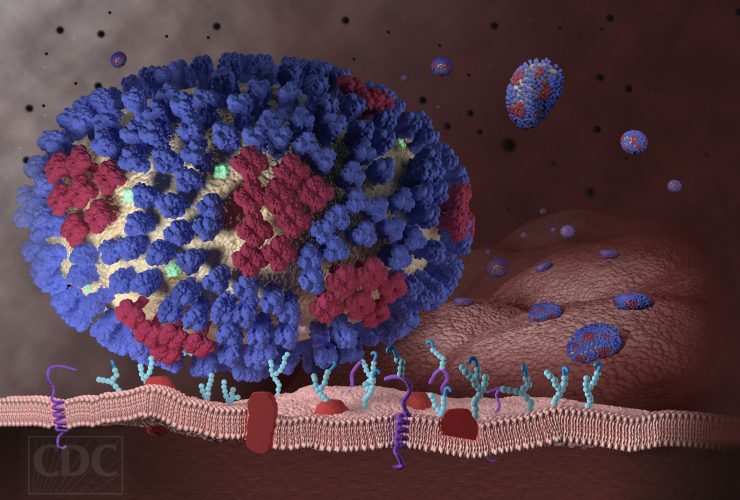

Influenza’s changeable nature – more about that shortly – doesn’t help, either. Influenza vaccines are built on what scientists see circulating worldwide, but a hallmark of the virus is its knack to change.

“That drives people nuts. It’s frustrating for everyone, believe me,” he says. “It can seem like a guessing game layered within a guessing game.”

But it’s an educated guessing game. More than 100 countries conduct year-round influenza surveillance and send data to five major laboratories, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta.

All of these labs watch for signs of “drift and shift.” Drift is when the virus changes only slightly, causing the immune system to not recognize the virus as well. That’s usually at play each year.

Harder to predict is shift, which is when an influenza virus makes a sudden and major change. When shift occurs, few people have immunity and it can lead to a pandemic, as the so-called swine flu did when it hit hard in 2009 and the Spanish flu did in 1918.

All this information guides the World Health Organization in its vaccine composition recommendations. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration makes the final decision about the specific formulations used nationwide.

Then manufacturers go to work, producing a handful of approved flu vaccines, most of which are grown in incubated eggs during the summer months. Although it’s a proven method, it’s not perfect, Goad says. Egg-based vaccines are slow to grow and slight changes occur when the virus adapts to the egg environment.

Flu Research

Public health officials are happy to see promising research into other cell-based growth mediums that could lead to better vaccines, as well as speedier turnarounds in production should a shift occur. Among the major supporters of such research is the Department of Defense.

Meanwhile, the flu vaccines injected into your arm at the pharmacy, work or school clinics are safe and effective, and if enough people got them flu-related deaths and hospitalizations would drop, Goad says.

“It doesn’t matter where you go to get the vaccine as long as you get it.”

Display image at top/A graphic representation of a generic influenza virus. (Courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control)