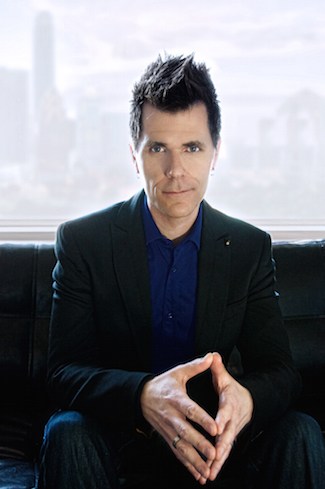

Jeff Garvin ’98 published his first novel, Symptoms of Being Human, earlier this year. Then he watched as news events continued to push gender-identity issues – the central struggle of his utterly engaging young hero/heroine – toward the front of our cultural conversation.

Meet the author

Garvin will appear at Barnes & Noble on July 23 as part of the 1888 Center’s Summer Writing Project.

From Caitlyn Jenner to the North Carolina bathroom law to the end of the ban against transgender men and women in the military, a once-obscure segment of society has entered the mainstream consciousness. In June, researchers estimated some 1.4 million U.S. adults identify as transgender, doubling previous calculations.

“It’s the story that chooses the writer,” says novelist Jeff Garvin ’98.

Riley Cavanaugh, Garvin’s main character, is a bright high school student with an affection for punk rock who is at once awkward and cool. Riley is self-conscious in all the usual adolescent ways, with one huge addition: Riley is gender-fluid — not exactly transgender, but a shade of gender dysphoria somewhere in between. It means waking up every morning waiting to see if today feels more like a masculine day or more like a feminine day. And it makes the teenage angst of figuring out what to wear infinitely more complicated.

“It’s like I have a compass in my chest, but instead of north and south the needle moves between masculine and feminine,” Riley says. And this: “The world isn’t black or white, yes or no. Sometimes, it’s not a switch, it’s a dial.”

Riley’s already complicated world is further complicated by transferring to a new school after a psychiatric crisis, and by being the child of a U.S. congressman up for re-election. One of the deft accomplishments of Garvin’s writing is that the reader is never quite sure either whether Riley was born a boy or a girl, and Garvin avoids using “he” or “she” throughout.

The reader’s other great mystery is Garvin. How does he seem to know this world so well? Garvin is straight and married, but his life’s many roles – actor, songwriter, performer, writer – have molded what seems like an innate ability to understand what it must feel like to be inside someone else’s skin.

The story was born after Garvin was in a car with someone he didn’t know well in 2013 and the discussion turned to a court case involving a high school student using facilities other than those meant for the gender the student was assigned at birth.

“The driver, I’ll call her Jane to protect her innocence, she brought up this court case,” Garvin says. “I thought, ‘Boy, this is awesome. We’re going to have a conversation about acceptance and openness and love.’ The next thing that came out of her mouth was, ‘Isn’t that gross?’”

Soon Garvin was researching gender dysphoria blogs, YouTube videos, a national transgender discrimination report and academic and other sources.

“I’ve always believed it’s not the writer who chooses the story. It’s the story that chooses the writer,” he says. “My first thought was, ‘I wish someone else would write this.’ And then, ‘I guess I’m going to write it. How can I write about someone in high school struggling with gender identity?’”

Garvin did it well, and one of his most satisfying moments was the stamp of approval from a

Lambda Literary review

that called his novel “a gorgeous debut” and “a punk rock love story to the queer community from an exceptional writer.”

Also an actor – he appeared in

The Wonder Years

,

Caroline in the City

and

Roseanne,

among other shows – Garvin earned a BFA in film production from

Dodge College of Film and Media Arts

and has tried his hand at screenwriting. He also spent years in a band, 7k, writing songs and touring the U.S.

At not quite 40, Garvin still somehow seems to understand teenagers.

“I used to be one,” he says. “I guess my whole thing on teenage voice is I remember what it was like to be a teenager, and some part of me never grew up.”

Riley, of course, is growing up in a very different era: what might have been a diary with a lock becomes an anonymous blog whose readership grows exponentially. There is the magical first follower, then an explosion to tens of thousands and growing.

Riley’s moments of crisis progress from being called “it” or “tranny” to counseling a suicidal stranger online, and then to being outed and assaulted. Friendship and faithfulness to oneself — whatever that comes to mean — triumph in the end, as does Garvin. The final pages of the book include a list of resources, among them the Trans Lifeline, the National Center for Transgender Equality and the Transgender Law Center.

Garvin feels awkward speaking for LGBT groups “because I’m a guest in that community.” He also is something of a hero, receiving emails from people who identify as transgender. “I’ve gotten a couple of emails saying, ‘Thank you for writing this. I highlighted portions and gave it to my friend as a way of coming out.’”

Garvin feels particularly strongly about one thing: “It needs to be talked about,” he says. “We’ve got to get this situation normalized. Get people to accept that it’s normal.”

Genderfluidity is in-fact considered part of the trans community! Because genderfluid persons do not identify as what they are assigned with at birth all the time. Plus, not all transgendered persons want to transition. For some, their transition to a more comfortable, less dysphoric life, simply means being able to present in the way they are most comfortable (changing their hair, dressing the way they’d like, getting one surgery but not the other, or undergoing only light HRT to become more neutral looking).