Peat samples collected by Professor Jason Keller as part of federal study may hold clues to bogs’ impact on climate change.

Peat bogs have long been a source of bogeyman legends, soil amendments for finicky azaleas and even poetic inspiration for no less than Emily Dickinson.

But bogs may have something else to unleash on the world. Stored within their marshy layers is one-third of the planet’s soil carbon. That’s because eons of long, cold winters slowed decomposition. Organic matter from plants and trees accumulated and became, well, bogged down. But with climate change and warmer temperatures, will decomposition speed up, causing bogs to rapidly release methane into the environment? Or could warmer temperatures actually kick off more plant growth, creating ever denser bogs?

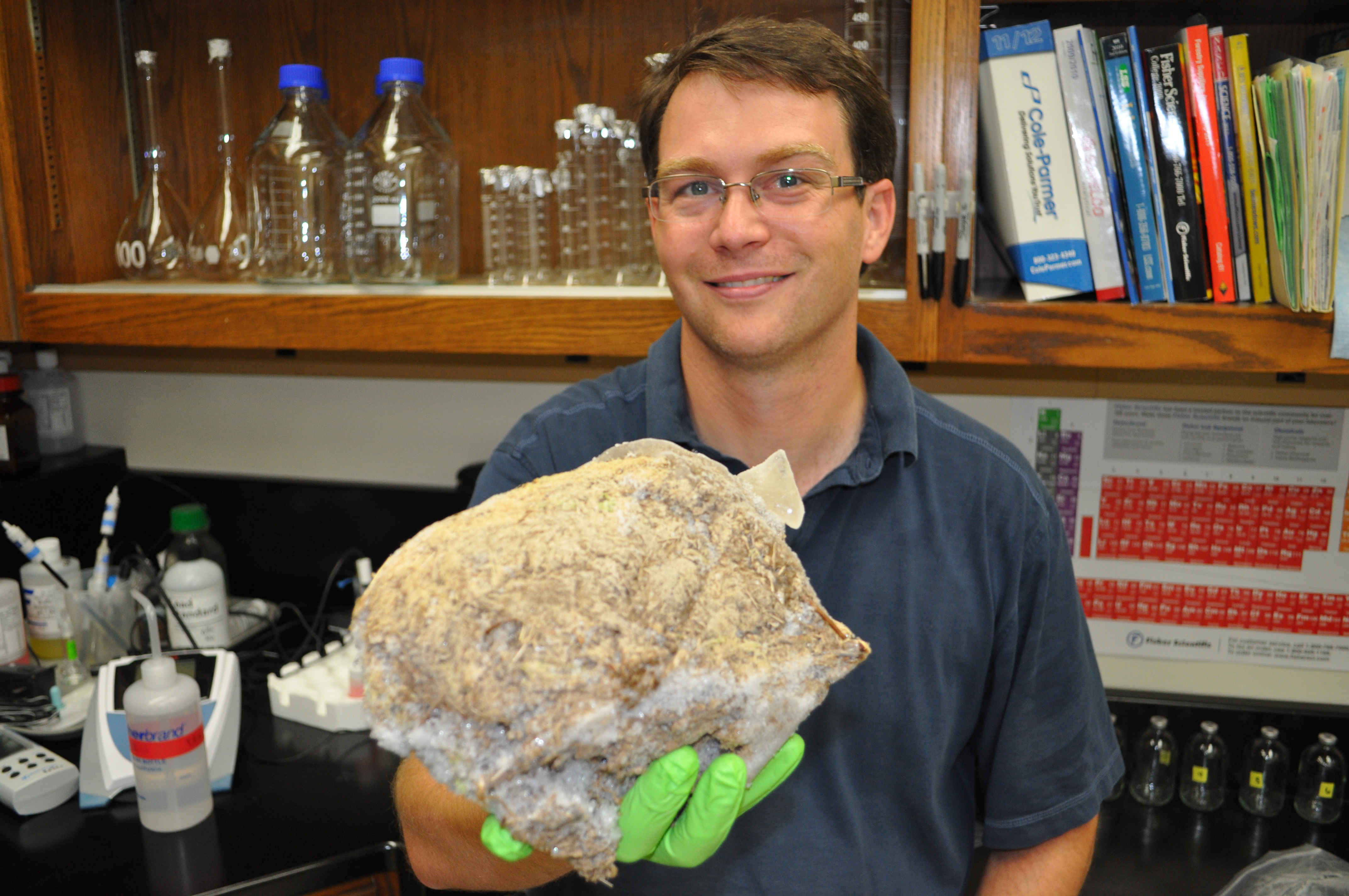

Those are just some of the questions Assistant Professor Jason Keller, Ph.D., hopes to answer as part of a team of scientists awarded a three-year, $1 million federal grant to study peatland warming. Their work is part of a long-term study organized by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory and aimed at tracking bogs’ decomposition and impact on global warming. Chapman’s share of the grant is $400,000.

“What it helps us do at the biggest scale is understand the links between climate change and ecosystems,” said Keller, a geochemist with expertise in coastal wetlands and marshes, as well as peatlands.

In essence, the experiments will require scientists to heat sections of the bogs by several degrees to replicate global warming. The study is the first of its kind, Keller said.

“Nothing like this has ever been done in a peatland. The technology they had to develop just to be able to do this is really impressive,” Keller said.

That technology is a set of 35-foot wide warming chambers which Oak Ridge engineers designed and installed in sphagnum bogs in a swath of National Forest in northern Minnesota. Keller and other scientists from the University of Oregon, the lead institution on the grant, and Purdue University

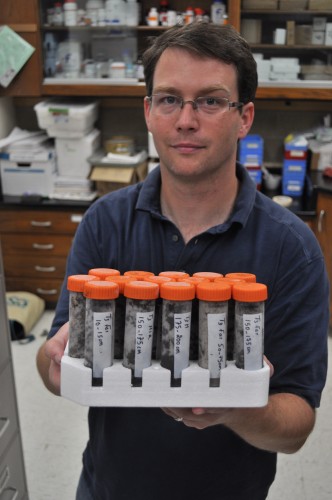

visited the site this summer. Their main focus was to collect sample soil cores, so they’ll have starting point data to compare with the warmer soil samples to follow.

The chambers look a bit like cylindrical homes of the future. But what they’ll allow scientists to study is the potential future of bog decomposition, a process which creates methane, a potent greenhouse gas. One focus of the project will be to use carbon-14 dating to measure the age of the carbon released by the bogs, Keller explained.

“From that we’ll be able to determine if the methane is coming from new carbon, by plants that recently died, or if that methane is coming from carbon 10,000 years old. So we’re really getting at this question of whether that deep-stored carbon that’s been there for thousands of years is suddenly being burned off as methane and being returned to the atmosphere,” Keller said.

Much of the lab work will be done in Keller’s facility in the Schmid College of Science and Technology, where he plans to involve his undergraduate chemistry students and a post-doctoral technician. And, naturally, he looks forward to the site visits as well.

“I actually think (bogs) smell really good,” he said. “They’re gorgeous, just gorgeous – if you can get past the bugs.”

Add comment