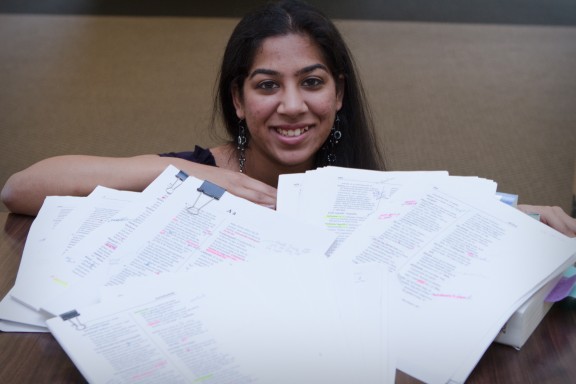

Priya Shah ’13 with edited pages of the trilingual Shiwilu-Spanish-English dictionary she is helping Pilar Valenzuela, Ph.D., create for a community in the Peruvian Amazon.

The faded mosquito bites dotted around Priya Shah’s ankles will disappear, making that particular reminder of her January interterm studies in the Amazonian rain forest a mere memory.

“They were huge,” Shah said with a laugh, brushing at her ankles near the end of the spring semester, months since her trip to the Amazon. “But they’re going away.”

Besides, Shah ’13, a Spanish and history double major, says encounters with mosquitoes were a small price to pay for the far more enduring work of helping to create a trilingual dictionary, a lasting documentation of Shiwilu, one of the Amazon’s disappearing languages. Over the past five years several students have traveled with language Professor Pilar Valenzuela, Ph.D., to an area of northeastern Peru to work with the Kawapanan Project, created to document the Shiwilu language. Students in the language professor’s advanced Spanish linguistics classes have also helped. But for Shah it has become a scholarly passion. Twice she has gone to the remote villages there to assist, as well as conduct her own field research. She returns this summer to the capital city of Lima to study extrication trial records related to the Spanish Inquisition.

Professor Pilar Valenzuela and Priya Shah ’13, in back, with Emerita Guerra and Julia Inuma, two Shiwilu speakers who shared their knowledge of the Amazonian language.

“I’m super interested in Latin American history. The whole colonial impact on indigenous populations interests me,” she said.

Ultimately, she hopes to pursue a Ph.D. in the field and build a career in teaching and university research, a path shaped by her undergraduate research experience, she says.

“It’s really given me a lot of guidance. I kind of know where I’m going now,” says Shah, who grew up in Irvine.

And it all began with the word-by-word task of creating a 6,000-entry dictionary of Shiwilu, a language now spoken by just 30 people who live near Peru’s Huallaga and Marañón rivers. Since 2005 when a village leader asked Valenzuela to document the language, she has frequently visited the region, studied and learned the language and done most of the translation into Spanish.

In 2007 Chapman University provided support for the project, and in 2009 Valenzuela was awarded a National Science Foundation grant to continue her work on Shiwilu, as well as Shawi, a sister language from the Kawapanan linguistic family. Since then the project expanded to include the transcription of folktales. In 2011 Katlin Kane ’11 transcribed from Spanish into English a handful of stories collected by a 1950s researcher. She also visited the villages to help fill in gaps in the tales. Those are being published in cooperation with the

Catholic University of Peru.

Shah joined the project in summer 2011, at the end of her sophomore year. Valenzuela had spotted Shah’s aptitude for languages and saw a student who “is especially inclined toward analyzing languages, not just reading and writing the language … It’s very hard. She’s very detail-oriented, which you have to be, and also she was willing to learn the culture.”

Transcribing dictionary entries from Spanish to English is the lion’s share of Shah’s work, but her field visits to the region allowed her to conduct spoken language recordings, which deepened her understanding of Shiwilu’s nuances. She was intrigued by a glottal stop, or short pause used in by the speakers, and by their attention to detail. As members of a river community, “they have more than 20 different ways to say ‘catch fish’ because they catch fish in so many different ways,” she says.

Occasionally, there is a surprise.

“One word we were surprised to get was whale, because they don’t have whales there,” she says.

During the study trips Shah also completed her own field work, including a study of why the language of the neighboring Shawi people endures, unlike Shiwilu. Shah’s research found that the Shawi were more geographically dispersed and that a taboo existed against village women speaking Spanish. The two factors effectively served as lifelines for their language, she says.

It’s unrealistic to expect that the dictionary will revive wide use of the language, Shah says. But it will help preserve a slice of the people’s ancestral identity and perhaps some of its heart and soul, as well as unique and valuable knowledge, Shah says.

“There are so many fruits and vegetables. There are like 20 or 30 different types of potatoes, and they have different words for all of these. They have different types of garlic,” she says. “There are animals, plants and medicinal words they use. It’s a wealth of knowledge.”

By December, Valenzuela hopes to have the final dictionary and a brief grammar guide ready to take to a printer in Peru, after which she’ll present it to the villagers.

“It will be the first book that they are going to have,” she says. “They are going to have the dictionary.”

[…] Read more in Happenings … […]

This is fascinating and very important work! Every time the world loses a language, it loses it’s world view, discourse style, and cultural distinctions. We lose an entire way of knowing and understanding as well as how to live and be in the world, when a language is lost. As humans interact in different environments, they develop knowledge that can most effectively be shared through our means of oral and written communication. I applaud Dr. Valenzuela and her students for taking on this arduous yet valuable endeavor that will add to the record of humankind.

Anaida Colon-Muniz