As universities nationwide are stepping up to address the underrepresentation of Latinx students, there is still much work to be done to improve first-generation graduation rates.

But one critical component to the academic success of first-generation students is currently understudied—their relationship with their families.

Fortunately, Assistant Professor Stephany Cuevas of the Attallah College of Educational Studies at Chapman University is researching how parents, siblings and extended family support first-generation undergraduate students. This work is part of Cuevas’ long-standing research agenda focused on improving outcomes for Latinx students in higher education.

“There may be an historic increase in Latinx students in higher education but they’re not necessarily graduating,” Cuevas said. “So I am approaching this issue from the perspective of identifying how we can work with systems that are already in place and the support structures that are already in place.”

According to 2021 data, only 32% of Latinx students aged 18 to 24 were enrolled in college compared to 33% of Black, 37% of White and 58% of Asian Americans of the same age. In the same year, 23% of Latinx students ages 25 to 29 had earned a bachelor’s degree, up from 14% in 2010.

However, these numbers of degree completers still lag behind Black (26%), White (45%) and Asian American (72%) populations, highlighting the challenges Latinx students face Latinx students face in accomplishing their higher education goals.

“I’m very interested in finding the ways that institutions can partner with families to help students graduate to improve these numbers,” Cuevas said. “My research can be used to help us design programming to help demystify what higher education is for families of first-generation students.”

Exploring Family Support

Cuevas’ work is helping move the needle through identifying the nuanced role that families play in the education of their children and how universities can help engage and support this critical role.

In her recent study, “‘I Tell Them Generics, but Not the Specifics’: Exploring Tensions Underlying Familial Support for First-Generation Latinx Undergraduate Students,” Cuevas interviewed 16 first-generation college students about their experiences. Cuevas found that while students often feel supported by their families, they also experience significant frustration and tension due to their families’ limited understanding of college life.

The tensions included family’s unfamiliarity with college culture, bidirectional behaviors of protection from stress and continued family interactions.

Students described how their families could not fully understand the immense stress they grappled with due to the increased workload and need to perform academically.

“I would really like them [parents] to understand the stress thing,” said Alex, a student who took part in the study. “That it is not something you can really just get out by running or something. Stress isn’t really something you can just get rid of easily. When they’re not understanding, that can be even worse on me because I feel more alone and that nobody understands me. So, I really wish that I could tell them on a deeper level how I feel and how stressed I am.”

Students noted that they kept information from their families to prevent further worry for them. One student hid his academic probation while another withheld her fears of letting her parents down.

Students also reported having to contend with continued family responsibilities while attending college, including helping parents financially, mentoring younger siblings and extended family members with college applications, and household responsibilities like cooking and cleaning. Students found it difficult balancing these responsibilities with their studies.

“It is essential to consider and address these tensions to further support these students’ retention and academic and socioemotional wellbeing,” the study concludes. “Doing so will help students succeed and develop, foster, and sustain stronger familial ties.”

Students who feel supported by their parents experience better mental health, smoother social adjustment and improved academic outcomes, including higher GPAs and graduation rates. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for developing better support systems for first-generation Latinx students, ensuring they can thrive both academically and personally.

With this in mind, Cuevas’ research is critical to better understanding how universities can support parents of first-generation students. It could help improve the success of first-generation students across the educational landscape. It’s already being applied at Chapman.

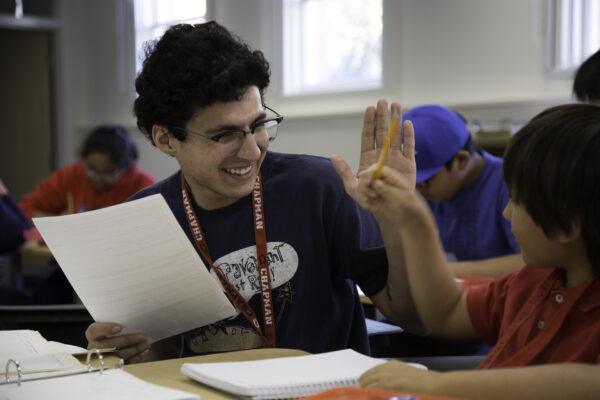

Earlier this year, Cuevas presented the research to families during the orientation for the Promising Futures Summer Bridge Program, which helps prepare incoming first-generation students for life at Chapman. Families are also encouraged to attend resource fairs to better understand what is available to their child.

“My hope is that families feel empowered after we walk them through the different ways they can get involved and take ownership of the important role that they continue to have in their children’s education,” Cuevas said.

Future Research

I n alignment with her overall goal of increasing first-generation student success, Cuevas recently received a $49,015 grant from the Spencer Foundation to research the educational experiences of Central American unaccompanied children, an underrepresented group in educational research. The study is in collaboration with Dr. Martha C. Franco, assistant professor of sociology at CSU Long Beach.

n alignment with her overall goal of increasing first-generation student success, Cuevas recently received a $49,015 grant from the Spencer Foundation to research the educational experiences of Central American unaccompanied children, an underrepresented group in educational research. The study is in collaboration with Dr. Martha C. Franco, assistant professor of sociology at CSU Long Beach.

Within the last few years, there has been a significant increase in the number of Central American children coming to the United States without a guardian. After being detained in immigration detention centers, they have been released to sponsors and are required to attend school.

“Family can look very different for these young people,” Cuevas said. “It may not be biological parents who they consider family.”

Many of the children arrive in the U.S. with a significant amount of trauma and schools are not well equipped to support them, Cuevas said. The research team is aiming to identify how schools can support students by better understanding how the students define family and the perspective of educators.

“These students have a different kind of lived experience than other first-generation students,” Cuevas said. “I can bring my expertise in family into this subject so we can better understand them and identify solutions for schools.”